While scholars of old master paintings have begun to accept the existence of multiple originals, old master drawings specialists continue to be reluctant to do so. Postulating the existence of a second autograph version of a drawing seems to be perceived as a failure of connoisseurship and is not widely accepted in monographic publications or by the art market. By presenting examples of documented commissions for second versions of drawings as well as paintings, this paper aims to reassess our thinking regarding the existence of autograph copies and highlight their importance as valuable documents of early modern workshop practice worthy of further study.

Scholars of Old Master drawings are often confronted with two versions of the same composition that are virtually identical. In my work compiling a catalogue raisonné of the drawings of Paul Bril, I came across seven sets of such drawings. In all cases I could distinguish the version that was the first or original version by Bril. Despite my best efforts, and the warnings of the honoree of the present volume, however, I could not eliminate the possibility that the second version was also by Bril, because the hands of the two sheets were so close. In many cases, the version I picked as second, or, I suppose, as somewhat inferior, had always been considered to be by Bril; sometimes it was the only version known or was listed as being the original or first version, if both were known. Sometimes the second (or third) sheet was just different enough to warrant the idea that it was by a master copyist working in Bril’s workshop, but most often, the penmanship was identical with Bril’s. Because of this discrepancy, I labeled all seven sheets “copy versions,” with the ones definitely by Bril designated as “autograph copy versions.”

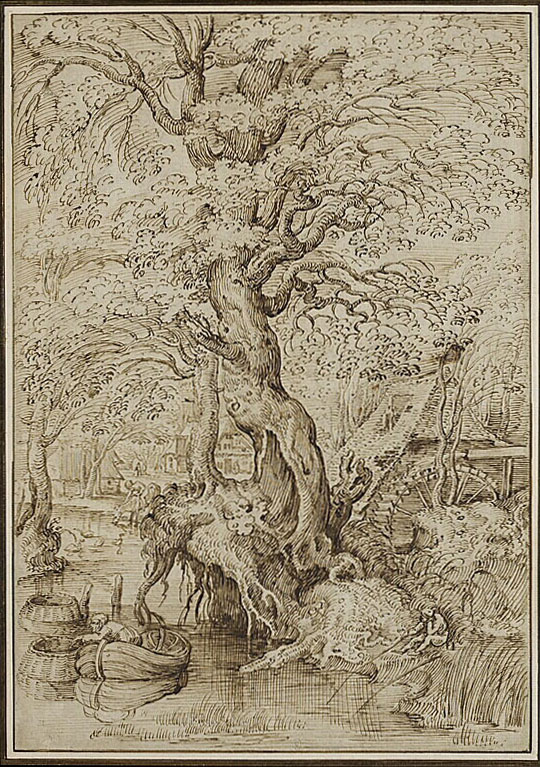

I am not the only scholar to have posited the existence of second versions or autograph copies of drawings by a given artist. Konrad Oberhuber did so in his monograph on Bartholomeus Spranger (1970), as did Wolfgang Adler in his book on Jan Wildens (1980) and Anne Charlotte Steland in her book on Jan Asselijn (1989). 1However, most drawings scholars have historically shied away from affirming the existence of multiple autograph versions of a single drawn composition. Hans Mielke in his definitive book on Pieter Bruegel’s drawings (1996) clearly had difficulty with this subject—he discussed two versions of the same composition in Brussels and Paris (fig. 1 and fig. 2), one that Frits Lugt had accepted as the original, and the other that he and Konrad Oberhuber accepted. Interestingly, Mielke illustrated both, indicating to me that he had some doubt as to the status of the so-called copy in Paris.2 To me, the Paris sheet is a clear example of a drawing that could very well be an autograph second version, a concept that I think Mielke was unable to accept. There seems to be a perception that the existence of such a duplicate not only diminishes the value of the original but also calls into question the accuracy of the scholar’s eye. The idea that a draftsman could have copied himself is not widely accepted because drawings are often valued for their supposed connection with disegno, the inventive process of the artist—his creative spark, his thought process made visible on paper. An autograph copy is therefore anathema, its purpose seemingly at odds with the drawing’s perceived, or at least desired, value.

Is this perception correct? Is it true that draftsmen never copied themselves? How can we prove or disprove this without risking our reputations as connoisseurs? As early as the 1960s, John Shearman posited the existence of multiple originals in the painted work of Andrea del Sarto.3 More recent scholarship has continued to show that artists often copied their own paintings and that such autograph copies actually had an important place in the function of the early modern workshop. In addition, they can tell us a great deal about the influences of collectors on one another and also help us write the history of aesthetic preferences. If it can be proven that artists also copied their own drawings, then it is incumbent on drawings scholars to accept fully the existence of multiple originals, thereby providing an open environment for their study that will eventually lead to a better understanding of their role in the history of art.

The desire for authenticity in works of art is not new. As Jeffrey Muller has deftly outlined, this desire can be traced back to Plato and on through the Renaissance to Enea Vico’s Descorsi of 1555, in which the author devoted an entire chapter to the detection of forgeries and copies of ancient coins. In 1560, Felipe de Guevara drew a distinction between originals by and imitations of Hieronymus Bosch, and in 1620 Giulio Mancini discussed the problem of faithful copies.4 Mancini, in fact, was an advocate of what we now call Morellian analysis for the detection of copies: “especially in those parts which demand resolution and cannot be well-executed in the process of imitations, as is true in particular for hair, beards, and eyes. Ringlets of hair, if imitated, will betray the laborious effort of the copy and if the copyist does not want to imitate them, then they will in that case lack the perfection of the master.”5

If the authenticity of a work of art is valued by collectors, this fact will be reflected in its price on the market. A collector does not want to risk being fooled by a skilled deception, even if executed by a close follower of the original artist, and so all copies, whether autograph or not, become suspect and therefore less attractive to the market. One of Bril’s autograph copies recently failed to sell at auction despite its high quality and previous acceptance as one of Bril’s more beautiful drawings.6 It is safer to reject any type of copy than to try and explain or understand gradations of variation from the original work. The high value placed on authenticity in the marketplace and in modern scholarship explains the historical absence of multiple originals in so many monographs and catalogues raisonné and the heroic efforts made to determine which of two versions of a composition is the first, or original, even though many scholars only do so reluctantly.7

Originality or inventiveness, as opposed to authenticity, has not always been as desirable in works of art. Richard Spear has pointed out that traditionally, religious works of art were valued for what they represented: conformity, even uniformity, was desirable and the element of error that might creep in because of personal invention was to be avoided.8 During the sixteenth century, the importance of an individual artist’s invention was recognized; yet, at the same time it was considered important to disseminate these inventions through reproductive prints.9 Jeltje Dijkstra’s work on the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in northern Europe indicates that up to one-half of late fifteenth and early sixteenth century paintings were commissions for copies of existing works.10 In the seventeenth century, Constantijn Huygens ordered Gerrit van Honthorst to make a copy of his portrait of Stadhouder Frederik Hendrik and Amalia von Solms for his own collection,11 and Michiel van Mierevelt owned a “supply of replicas” of his most famous sitters.12 Far from being a drawback, the fact that the design of the picture was not original was desirable. In these cases, collectors specifically requested copies of compositions that pleased them, not new inventions. Since authenticity was prized, the desired copy was often made by the original artist and thus the “autograph copy” came into existence.

Although collectors accepted and even requested painted autograph copies in the seventeenth century, apparently they did not value them as highly as originals. Recent research on the Netherlandish art market of the time has demonstrated that the first version of a painting generally sold for an average of 2.5 times the value of its autograph copy.13 Van Migroet and De Marchi in their important article on the subject rightly interpreted this as indicating that by the seventeenth century in northern Europe, the artist’s “invention” had become a valuable aspect of a work of art, a claim that can not necessarily be made for earlier centuries.14 Their work as well as that of Elizabeth Honig, however, serves to confirm the fact that autograph copies of paintings were common in the seventeenth century. In addition, in her excellent recent book on seventeenth century connoisseurship, Anna Tummers quotes Roger de Piles, who said: “There is hardly any painter who did not repeat one of his works because he liked it, or because someone asked him to make one exactly the same.”15

While the existence of multiple originals of paintings has been gaining credibility in the discourse of paintings scholarship, the subject remains taboo among scholars of drawings. One of the main reasons is that much less information survives regarding commissions for drawings than for paintings. If there were more, would we find that collectors also demanded second versions of drawings? If that were so, could Old Master drawings scholars then accept the existence of such sheets with more complacency?

I believe this question actually goes to the very heart of our discipline as drawings scholars. As Ivan Gaskell has pointed out: “in the printroom above all [where most drawings scholars practice], the ancient mysteries of an older, rival, priestly cult are practiced more or less undisturbed: the rites of connoisseurship.”16 Within this cult, any slight indication of doubt or wavering on the part of an expert is seen as a sign of weakness. Since connoisseurship is often considered the primary task of those writing about drawings, it follows that a scholar in the field rises or falls, is respected or not, based on the perceived perfection of his or her eye.

Gaskell suggested developing and advancing connoisseurship but “with a view to addressing new questions.” This is a challenge that I think we all should aspire to meet. Too often the discovery of an anomaly in our field such as “autograph copies” or “multiple versions” ends with doubt regarding the connoisseurship of the scholar as opposed to an effort to locate documentation as to why the supposed anomaly might exist. When a search does occur and successfully uncovers relevant information, this is sometimes seen as an attempt to justify less than successful connoisseurship as opposed to being an interesting new discovery that connoisseurship has helped make possible. To follow Gaskell’s suggestion to advance connoisseurship and thereby strengthen our discipline, in the present case one might look for convincing reasons why autograph copies or multiple versions of drawings exist, despite our misgivings about them. Luckily, we can turn to the work done by our colleagues who have studied this phenomenon in painting. As already discussed, second versions of paintings were often produced on commission. If we could find commissions for second versions of drawings, we would have convincing proof that artists copied their own sheets and that a specific market for these copies existed.

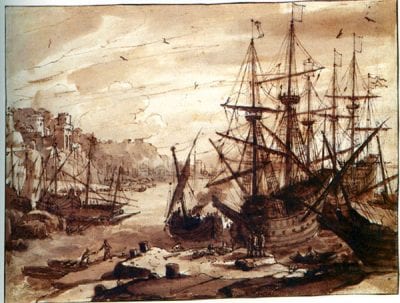

As it turns out, in the case of Paul Bril we have evidence that collectors came to his studio and were interested in copies or versions of works they saw there, although unfortunately the most direct evidence is, again, for paintings. From letters extant in the Ambrosiana we know that Cardinal Federico Borromeo ordered a copy of a painting Bril was making for Jean-Baptiste Crescenzi, which he had probably seen in Bril’s studio in 1610 (fig. 3). According to one of the letters, Borromeo wanted his painting to be the same or “even more beautiful,” with the same quantity of ultramarine blue pigment. This indicates he could and did specify what he wanted, and how exactly it should be different from the first version. The painting Bril produced for him, now in the Ambrosiana in Milan,17 is very similar to the Crescenzi painting, now in Brussels, with more ultramarine and with the significant substitution of a rocky outcropping where the ship had been.18 Perhaps even more intriguing, from the provenance it appears likely that Paul V ordered another copy of the same composition for his nephew Scipione Borghese and that for this patron Bril actually surpassed his two earlier efforts (fig. 4).19 In 1617, he made yet a fourth version for Cardinal Carlo de Medici, who had ordered two paintings from Paul Bril in October.20

If paintings collectors requested “copies” or “versions” of paintings, it seems quite plausible to surmise that they could have just as easily have requested a “copy” or “version” of a finished drawing from Bril. In fact, the great eighteenth-century drawings connoisseur Pierre-Jean Mariette indicated (although a century later) that Bril had a booming clientele for drawings:

“The reputation of Bril increased to such a level that amateurs were interested not only in his paintings but in his drawings as well. They eagerly demanded them from him, and that is why you find so many of them with such beautiful execution, because he did not do them for his own study, but rather took all the time he needed to finish them with as much care as he would his most finished paintings.”21

If he had such a large clientele who wanted drawings, no doubt there were those who commissioned copies of successful finished compositions. Not surprisingly, all of the drawings that I considered to be second versions were finished drawings.

Luckily, a drawing recently for sale at Sotheby’s essentially proves that Bril did make second versions of successful drawings specifically for collectors (fig. 5).22 In this drawing, which is not by Bril, the left side appears to copy a drawing by Bril of Saint Jerome that is currently in the Lugt Collection in Paris (fig. 6).23 The Lugt sheet is clearly a finished composition, for it has not been trimmed on any side. The right side of the drawing at Sotheby’s, however, is not represented in the Lugt sheet, and therefore it must have been copied from a lost original that included the entire composition. That would mean that the Lugt sheet, the draftsmanship of which is exquisite and could not be doubted as an autograph Bril, was also copied from this other, lost sheet. This is supported by the fact that the tree branch in the lower right of the Lugt sheet seems cut off in just the place that the tree branch continues in the Sotheby’s sheet. This indicates that the Lugt drawing is an autograph copy, or second version. What makes the drawing even more interesting for the current discussion is that it has an inscription underneath indicating it was made by Bril as a gift or possibly on commission for a friend, Paulus van Halmaele: Paulus bril amico suo.S.R. Paulo de Halmale / facebat. Romae ques di. 12 Aprilis-1604. The Lugt sheet is therefore an excellent example of Bril making a second version of a drawing expressly for a specific commission or purpose.

Besides commissions, Bril’s autograph copy drawings served additional, conventional functions that I think could pertain to similar works in the oeuvres of other artists. These functions would also apply to the extremely close copies probably made by professional copyists in the workshop, but that should not discount their importance. Autograph and non-autograph copy versions could have and did serve as modelli: in order to preserve the original for sale or later use, an artist could copy it or have it copied and use the copy in the workshop as a guide for further paintings, drawings or even prints. In fact, with Bril, all but two of the known pairs of original and copy versions have a print or an autograph painting or drawing after them, which demonstrates this function. Of course, the second version could also have been the one to go to the client, while the original remained in the workshop, which would explain why in some cases there are more autograph and even non-autograph versions of the first version of a composition. According to Honig and De Marchi and Van Migroet, artists and dealers were known to keep originals of paintings, or “principaelen,” in their ateliers and shops so that copies for resale could be made.24 The likelihood that the same held true for drawings, especially those of an artist like Bril whose finished sheets were cherished, is therefore very high.

In the sense that a second version preserves the original composition, it becomes a kind of ricordo. Like Claude’s Liber Veritatis, these drawings could have been records of particularly successful works of art that Bril sold to collectors. Ricordi served to preserve a record of drawings no longer in the shop, allowing them to be reused or shown to another client as examples of what an artist could do. Oddly, in his Liber Veritatis Claude made his own ricordo of the marine composition Bril painted originally for Jean-Baptiste Crescenzi (fig. 7).25

A more mundane reason that an artist may have copied his or her own drawings or had them copied exactly was to use them as study sheets for students. In Bril’s oeuvre, this suggestion is supported by the large number of painted or drawn copies of his sheets by other hands.26 Bril had a large workshop and these works clearly were actively used as training tools to immerse students in Bril’s signature style of landscape drawing.

Because of the survival of Mariette’s quotation, the Borromeo commissions, and some clear examples of the artist copying himself, it is easy to accept the existence of autograph copies in the oeuvre of Paul Bril. Combined with recent research into commissions for autograph copies of existing paintings, the evidence points to the fact that other artists must have done the same. The concept of “principaelen”—artists or dealers keeping originals in the shop so they can be reused for later compositions—could apply to draftsmen as well as painters. This would especially be the case with artists like Bril, who made finished drawings that were in high demand. Just as Anna Tummers called in her book for a revamping of catalogues raisonné to reflect the fact that many if not most artists used assistants in most of their paintings, I would like to call for the oeuvre catalogues of draftsmen to be revamped when necessary to include autograph copies. Once drawings scholars acknowledge the existence of these types of works, we can investigate their function more openly. Rather than be blinded by our prejudice for first versions, which is ultimately guided by the art market and the modern taste for invention and originality, scholars should appreciate that, among other functions, autograph copies and close copy versions could record lost compositions, indicate compositions that were of interest to students, and reveal the aesthetic preferences of collectors, making them extremely important documents for the study of early modern workshop practice. While multiple versions may undermine the original’s status as a unique object, they also elevate its status as a historically desirable object and therefore could provide new and significant information for the study of the history of art.

One final word of caution, stemming once again from the honoree of the present volume: the acceptance of the existence of autograph copies could cause renewed pressure on connoisseurs to accept as autograph drawings works that are clearly by another hand, however close to the original artist they may be. Even greater care must therefore be taken that this pressure does not affect the scholar’s eye; it should rather cause him or her to look even closer at the works in question and perhaps be even more discerning.