In Jean-François Millet’s work, what passed for direct observation was often borrowed from Dutch art. This essay reveals a previously unrecognized Dutch source, Jan Luyken, whose popular manual for housewives and book of trades were a treasure trove of source material for Millet’s depictions of traditional peasant labor. Luyken and other Dutch sources allowed Millet to cultivate an aesthetic that turned back the clock on industrialism and urbanization, perpetuating the myth that the agrarian lifestyle was resistant to time and change.

If one asks to see the visitors’ registry in the print room at the Bibliothèque Nationale, the unmistakable signature of Jean-François Millet (1814–1875) appears there in July 1837. It was Millet’s first year as a student in Paris. A pupil of Paul Delaroche (1797–1856), he was free to come and go at the library’s print room, which gave him access to innumerable treasures.

The Bibliothèque Nationale housed one of the world’s premier collections of Dutch prints, over a thousand by Rembrandt alone. In 1837, a special exhibition of highlights from the library’s holdings, including eighteen Rembrandt etchings, was on display.1 Millet’s familiarity with these prints is evident in a drawing of a crouching man hovering over a supine woman (fig. 1), which is clearly based on Rembrandt’s Jupiter and Antiope (fig. 2).2

Through a series of subsequent drawings based on this sketch, Millet transformed Jupiter and Antiope into rural laborers, taming the eroticism of the original version, adding a haystack in the background (fig. 3), reversing the poses, divesting Rembrandt’s figures of mythic significance, and finally rendering them as anonymous peasants in the French countryside (fig. 4). These Dutch-inspired figures are the first manifestation of a leitmotif in Millet’s later work: the peasant at rest.3

The metamorphosis of Rembrandt’s mythological figures into modern field laborers (a process realized over several decades) is a microcosm of Millet’s lifelong strategy of appropriation from Dutch art: slow, incremental modifications of form and subject, until the result is no longer identifiable with an antecedent, yet is still playing on subtle substrata of meaning.

Millet claimed he was “too wise to attempt a copy, even of something of my own; I am incapable of that sort of thing.”4 This glaring falsehood is a prime example of the artist’s feigned naïveté. In contradiction of his alleged hard line position on copying (“even of something of my own”), he was more than happy to reproduce several of his own compositions for collectors upon request.5 Numerous copies survive from his student years, and it was most likely under his first teacher, Bon Dumouchel (1807–1846), who was obsessed with the art of the Low Countries, that Millet began to borrow from Dutch prints.6

Nearly every major study of Millet acknowledges the presence of a Dutch aesthetic in his work. In 1970, Robert Herbert even referred to the 1850s as the artist’s “Dutch period.”7 The scope of the artist’s involvement with Dutch art, however, remains undefined. The most comprehensive discussion of the subject appears in Petra ten-Doesschate Chu’s French Realism and the Dutch Masters (1974) and is limited to five of Millet’s genre paintings from the 1850s.8 My own investigation reveals a new Dutch source for Millet’s compositions and a dependence on Dutch art far greater than previously assumed.

Among the challenges to understanding Millet’s relationship to Dutch art is that the artist himself had so little to say on the matter. Tight-lipped on sources in general, Millet allowed critics, dealers and other artists to intercede on his behalf. Foremost among these was Alfred Sensier, the Paris bureaucrat who later became his biographer, who cultivated Millet’s image as “a man of the soil . . . unconcerned with the niceties of civilizations lost in their refinements.”9

Recent Millet studies have uncovered a more nuanced individual than the untutored peasant projected by earlier literature on the artist. The son of a prosperous farmer, Millet left home with money in his pocket, never to work on the farm or experience the poverty so often depicted in his mature paintings. As Bruce Laughton has observed, prints, photographs, and drawings were the foundation upon which Millet built his signature aesthetic: “The woodcutters, the harvesters, the sheep-shearers, the shepherdesses, the water carriers, the winnowers and butter churners were first drawn in Paris.”10

In the capital’s museums, libraries, and print rooms, Millet assembled a visual repertoire that he would continue to develop throughout his life. A thorough knowledge of Dutch prints guided even some of the most informal of his rough sketches from the 1850s. Clearly dependent upon a specific Dutch source is Millet’s light pencil sketch Christ among the Doctors (fig. 5), adapted from Rembrandt’s etching of the same subject (fig. 6), which he would have seen at the Bibliothèque Nationale.

Millet not only studied Dutch prints, he also collected them. He was in the habit of asking friends traveling abroad to bring back prints and photographs with rural motifs. Prior to Félix-Bienaimé Feuardent’s departure for Italy in 1865, for example, he wrote:

If you find photographs, either from the antique, especially those less known here . . . buy them . . . Do not take anything out of Raphael; he is to be found in Paris . . . bring whatever you find, figures and animals. Diaz’s son . . .brought some very good ones, sheep among other things. Of figures, take of course those that smack least of the Academy and the model,–in fact, all that is good, ancient or modern, licit or illicit.11

An inventory of items found in the artist’s home after the death of his widow lists forty-five engravings by Dutch artists, of whom only three (Rembrandt, Adriaen van Ostade [1610–1685], and Jan Luyken [1649–1712]) are mentioned.12 One wishes the notary had listed them all individually, but the simple fact that Millet owned these engravings is of great significance. Luyken, the prolific late-seventeenth century Dutch illustrator, was relatively obscure in France when Millet acquired his etchings. Luyken’s two most widely circulated print series were an illustrated manual of mostly male trades, entitled Het Menselyk Bedryf (The Book of Trades), and a practical household manual for wives, Het Leerzaam Huisraad (The Tutelary Household).13 To each illustration, Luyken appended a moralistic verse.

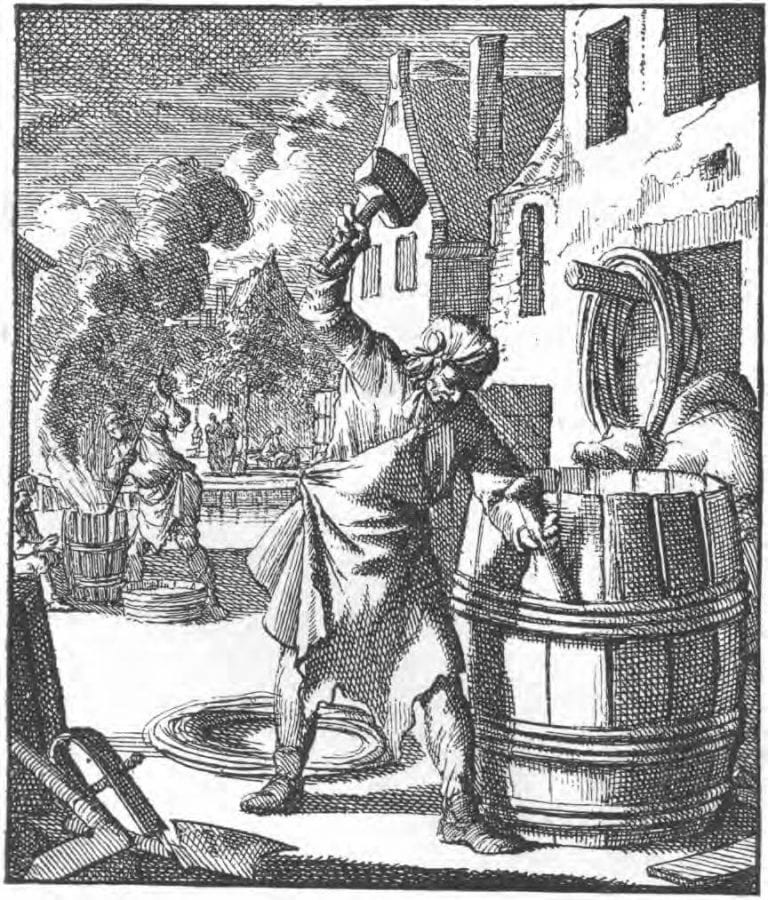

By the late 1840s, the visual evidence that Millet had acquired these prints is abundant. Consider The Cooper (fig. 7), which marks a decisive shift toward the powerful single-figure studies typical of Realism in the late 1840s, and the strikingly close prototype (fig. 8) in Luyken’s Book of Trades, a figure caught in mid-swing, bracing the barrel with his left foot and preparing to strike the chisel above the top hoop.14 Even the drape of his apron corresponds with that of Millet’s cooper. Young Mother Preparing the Evening Meal (fig. 9), a spare composition from the same period, achieves similar monumentality. Millet’s specific source was Luyken’s De Pan (The Pan) (fig. 10).

It is easy to see why these images appealed to Millet, a specialist in labor scenes. By the late 1840s, Sensier had begun to put pressure on Millet to focus on scenes of rural life. In 1851, while struggling to pursue his ambition to be a history painter in the competitive Paris art market, Millet received the following advice from his mentor: “My dear, if you wish to be understood apart from those paintings of children, bathers and mythology that you do for sale, you must put your mind to composing rustic scenes.”15 The collector then backed his own statement by purchasing twenty drawings of Millet’s field workers and assured him that scènes rustiques would guarantee him one major commission a year.16

As Christopher Parsons and Neil McWilliam have observed, Sensier’s ideological agenda in supporting rustic imagery was to reinforce “values located in the past.”17 For Sensier, the peasant was a more robust, pious creature than the urban dweller. The inherent virtue of traditional labor, implicit in Millet’s work, is explicit in Sensier’s review of the Salon of 1869. Chief among Millet’s admirable qualities, claimed Sensier, are a submission to nature and an iron-clad resistance to change: “The rustic of today, is he not the same as he has been for a thousand years, and as he shall remain, Man bowed beneath the sun’s fire or precipitation’s chill, earning his bread by the sweat of his brow?”18

Encouragement also came from socialist art critic and Dutch art scholar Théophile Thoré, who championed Millet and Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) at the Salon of 1861 as “country doctors . . . who come with solid recipes and unshakable health.”19 What were Dr. Millet’s cures for France’s sickness?–images of the laborer in the fields and the family at home. Thoré claimed that Millet’s peasant origins, as opposed to direct study, accounted for Millet’s resemblance to the Dutch masters. In praise of Waiting, for example, Millet’s 1861 depiction of a scene from theBook of Tobit (one of Rembrandt’s favorite bible stories), Thoré wrote: “Rembrandt shared this affection for the story of Tobit, from which he painted several episodes in an informal style, which recalls a bit the peasantesque style of M. Millet.”20 A clever turn of phrase that inverts their relationship, Thoré’s assertion that Rembrandt “recalls” Millet casts the Frenchman as the master and the Dutchman the follower. While chronologically impossible, it reflects the fact that works by both artists were simultaneously visible to the nineteenth-century public. The Louvre owned Rembrandt’s most dramatic canvas inspired by the Book of Tobit, The Angel Raphael Leaving Tobit and His Family. Visitors wandering through the Louvre after the annual Salon might stop to admire the Rembrandt and think of Millet’s portrayal of an earlier moment in the story.

In 1861 Thoré encouraged Millet and other Realists to take heart, for if Rembrandt had withstood centuries of critical abuse and still managed to make it into Europe’s major collections, they, too, would eventually receive the credit they deserved: “For two centuries now, lovers of grand Italian style have misunderstood Rembrandt, which has not, by the way, prevented him from finding his way into Europe’s principal museums and galleries. That ought to give the Realists some consolation for present injustices and hope for the future.”21

From Millet’s perspective, Luyken’s chief virtue was that his mild artistic personality did not interrupt the flow of Millet’s ideas. Bite-sized details from Rembrandt, Pieter de Hooch (1629–1684), Nicolaes Maes (1634–1693), and other genre painters could be borrowed from Luyken’s prints without the interference of the original source. Luyken’s De Pan, for example, is based on Rembrandt’s celebrated etching The Pancake Woman (1635). From Luyken, Millet could appropriate typical Dutch motifs already once removed. Additionally, the prints’ no-nonsense instructional purpose was in line with Millet’s espousal of traditional working-class roles. Yet Millet’s reworkings are not exact replicas. In The Cooper, for instance, Millet revises Luyken’s stylized approach to anatomy, bringing the upper arm into alignment with the rest of his body, and further dramatizing the physical exertion by lowering the perspective so the figure rises above us in profile. Unlike Luyken’s DePan, from which it is derived, Young Mother Preparing the Evening Meal eliminates extraneous detail and focuses on the figure, which it enlarges. What began as a central motif on a busy printed page is now a stark, monumental image. Nothing in our visual field competes with this formidable mother, a hieroglyph for hearth and home. Smaller adjustments, characteristic of Millet’s sensibility as an academically trained figure painter, contribute to the amplification of the pose. The key ingredients, the monumental figure and its reductive environment, are solutions to which Millet would return repeatedly throughout his career.

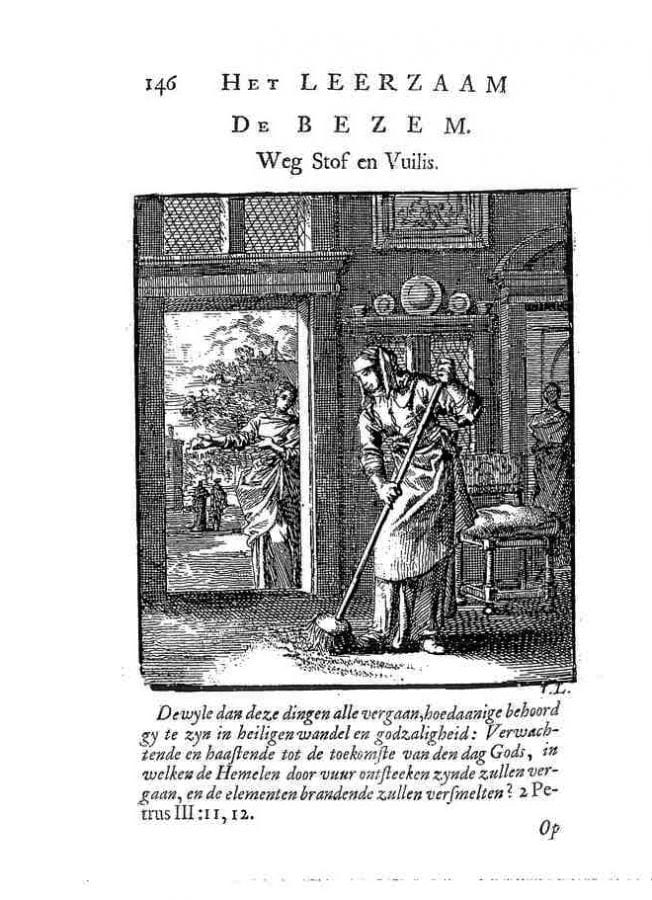

Nonetheless, Luyken’s prints were instrumental in reinforcing Millet’s persistent message of simplicity and timelessness. Millet’s Woman Returning from the Well (fig. 11) magnifies a detail in the background of Luyken’s illustration of a washtub (fig. 12). Weighed down by two buckets, Millet’s water-carrier places her weight on the same foot as Luyken’s figure). Her form is a perfect symbol for Millet’s own draughts, dipped from the ancient well, conveying balance and steadiness to the foreground. The figure in Millet’s Woman Sweeping Her Home (fig. 13) holds a long-handled broom in precisely the same stance as the seventeenth-century peasant in Luyken’s De Bezem (The Broom) (fig. 14), and the drawing borrows additional spatial elements from Luyken, such as the doorway toward which she is sweeping dust and the doorway behind her through which we glimpse another figure at work. Traditional forms of labor, lifted from Luyken’s prints, imparted an ageless quality to Millet’s scenes.

An experience recounted by the American artist Edward Wheelwright illustrates the power of Millet’s approach. One Sunday morning in the mid-1850s, Wheelwright and a group of friends stopped by Millet’s studio. The artist was not in, but they insisted on a tour, and Millet’s brother Pierre obliged, turning canvases that had faced the wall outward one by one. It was the final picture, Woman Mending by Her Sleeping Child (fig. 15), that rendered the audience speechless. As Wheelwright recalled:

At last was brought out from its hiding-place a picture representing the interior of a peasant’s cottage. A young mother was seated; knitting or sewing, while with one foot she rocked the cradle in which lay a child asleep . . . Through the open window the eye looked out into a garden where a man with his back turned appeared to be at work. The whole scene gave the impression of a hot summer’s day; . . . you could almost hear the droning of the bees, and you could positively feel the absolute quiet and repose, the solemn silence, that pervaded the picture. All those at least felt it who saw the picture upon that Sunday morning. A sudden hush fell upon all the noisy and merry party. They sat or stood without breathing. The silence that was in some way painted into the canvas seemed to distill from it into the surrounding air. At last Diaz said in a low voice, husky with emotion, Eh bien, ça, c’est biblique.22

While any tranquil scene of a mother and infant might invite associations with the Madonna and Child, this one did so with particular force because of its direct, yet tasteful, quotations from another more famous picture: The Carpenter’s Household (fig. 16), by Rembrandt. The work was in the prestigious Salon Carrée of the Louvre, and by the 1850s numerous reproductions of it had entered into circulation. When Millet moved to Paris in 1837, it was among the black-and-white illustrations in L’Artiste, and for the Exposition Universelle of 1855, Charles Damour duplicated the composition in an engraving.

When examined side by side, similarities between Millet’s Woman Mending by her Sleeping Child and the Dutch masterpiece are immediately visible. Millet’s somber interior, the crimson cradle with its diagonal lines leading back into space, the woman seated at its far edge, and the enticing glimpse out the window into the landscape are clearly indebted to the earlier composition. Little wonder Millet’s guests found his image biblical. They were predisposed to read it that way. Their unconscious familiarity with the religious scene on which it was based elicited an immediate, collective response from the artists. The most tantalizing link with Rembrandt (singled out for comment in Wheelwright’s description) is the male laborer whose crumpled hat, lowered head, and rounded shoulders are taken directly from Saint Joseph in The Carpenter’s Household.

Woman Mending by Her Sleeping Child is certainly not a copy, nor even an easy homage to Rembrandt. It is a prime example of Millet’s shrewdness in employing Dutch figures and themes for his own purposes, and evoking associations without revealing specific sources.23 As in his other compositions that borrow from Dutch art, he enlarges the figure of the laborer. In this case he also separates the figures from one another, and in contrast to Rembrandt’s cozily crowded space, Millet’s interior contains only the mother and child. In accordance with the domestic ideals of the late nineteenth century, he removes the male laborer from the house and eliminates the figure of Saint Ann.

Commenting on Millet’s compositions in the Salon of 1859, critic Mathilde Stevens wrote, “Labor is the holiest and most fertile form of prayer. That is why Millet’s paintings make such an intense and deep impression. These paintings are the most moving and eloquent of prayers, the prayers of simple men, their heads bent towards the earth.”24 For Millet, as for Luyken (a devout Mennonite), work was the path to salvation and a dimension of his imagery to which viewers responded favorably.

As Robert Herbert understood in 1976, the core motifs that serve as the basis for nineteenth-century peasant iconography were drawn as frequently from art as from life. “Without this absorption of earlier arts,” he wrote, “peasant genre would not have had such wide currency in the nineteenth century, for it would not have had this deeply sensed cultural substructure, it would not have contained these associations–both conscious and unconscious–which surround a form and give it meaning.”25 Recycled motifs are a common feature of nineteenth-century peasant painting and a crucial stratum of its significance. As Alexandra Murphy more recently acknowledged in her catalogue of Millet’s drawings, “in his search for intimate subject matter, Millet must have turned to his favorite old masters, as well as to his own back yard.” 26

This goes straight to the heart of Millet’s modus operandi, although the artist would surely have denied it. Millet’s brilliance lay in his capacity to gauge his audience’s appetite for traditional forms and deliver it in the guise of unvarnished truth. Contemporary descriptions of Millet’s work supported the mystification of his process. Sensier characterized the artist’s drawing, Winter Evening (1867) as possessing “a feeling, a light à la Rembrandt.”27 In 1875 Paul Mantz, who was a Dutch art specialist actively involved in the revival of Frans Hals (ca. 1581–1666) and no doubt recognized that Millet’s debt to the old masters was far from inadvertent, nevertheless praised Millet’s “almost unconscious remembrance of methods dear to the old masters.”28 Millet himself once claimed, to Thoré, that he “avoided with a sort of horror . . . anything that bordered on the sentimental.”29

At least one nineteenth-century observer was unconvinced by such protests. Camille Pissarro, fifteen years younger and initially an admirer of Millet’s work, reacted with exasperation when a friend, Hyacinthe Pozier, burst into tears before The Angelus at the Millet retrospective in 1887. Pissarro dismissed the picture, and Pozier’s reaction, as sentimental idiocy:

I went to the Millet exhibition yesterday . . . There I ran into Hyacinthe Pozier, he greeted me with the announcement that he had just received a great shock, he was all in tears, we thought someone in his family had died. Not at all; it was The Angelus, Millet’s painting which provoked this emotion. This canvas, one of the painter’s poorest . . . has just this moral effect on the vulgarians who crowd around it: they trample one another before it! This is literally true–and makes one take a sad view of humanity; idiotic sentimentality which recalls the effect Greuze had in the eighteenth century . . . a sentimentality that one day will embarrass all true artists.30

Pissarro’s implication is that Millet’s work is derivative and lacks on-the-spot immediacy (Jean-Baptiste Greuze [1725–1805], whom Pissarro mentions, also pilfered from Dutch sources). These are refreshing words, coming as they do from a frequent observer of the peasant at work. As someone who preferred to grapple with the frustrations of accurately rendering the natural world, Pissarro recognized Millet’s works as manipulative fictions. The utopian anarchist’s prediction that Millet’s paintings would one day embarrass “true artists” was, however, far from the mark. Less savvy artists, including the young Vincent van Gogh, would soon be inspired to abandon the traditional rigors of the painter’s craft in favor of spontaneous recording from life, believing that was precisely what Millet had done.