Throughout the seventeenth century, Amsterdam demolished buildings as it carried out expansions and made strategic decisions about its defenses. This essay argues that viewers attached images of demolished buildings to political and social alliances that were directly related to the sites of demolition. Images of such sites allowed viewers a means of imaginatively undoing changes to the city by reactivating memories of the sites in their pre-demolition states.

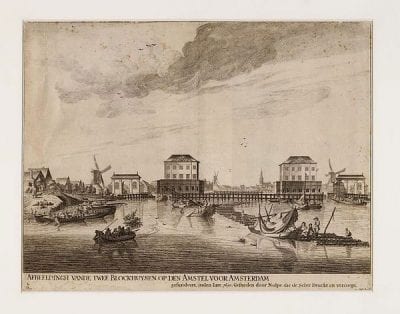

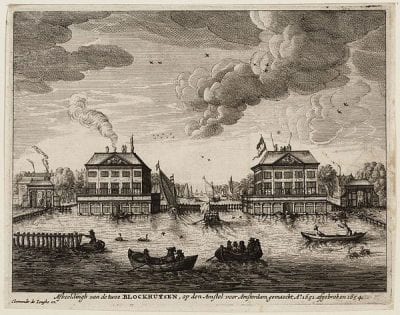

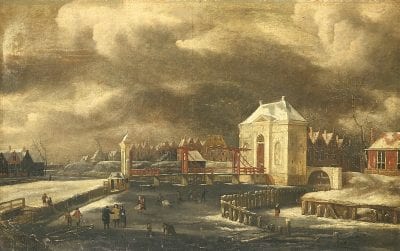

Jan Abrahamsz Beerstraten’s painting of the Heiligewegspoort (fig. 1) shows the Amsterdam city gate that once stood on the present-day Konigsplein. The gate, rebuilt in 1636, was demolished in 1664 during the so-called fourth expansion of Amsterdam to make way for the westward continuation of the Herengracht.1 Beerstraten’s detailed representation of the gate and its surroundings includes the frozen canal outside the city, with skaters and walkers enjoying the winter day among traders making their way through the gate. The scene suggests an eyewitness account of the gate, yet Beerstraten signed and dated his painting 1665, a year after its demolition. The gate appears in at least ten known paintings, including two works by Abraham Beerstraten, recently sold at auction, and several by Jan van Kessel and his followers. It features in at least a dozen prints and drawings, as well—a surprising number of images for a short-lived structure of no obvious special importance. Indeed the Heiligewegspoort is not a unique case. The blockhouses on the Amstel river in Amsterdam (fig. 2), in spite of standing for only three years (1651–54), also appear in a large number of images.

These buildings were torn down because they no longer served the purposes for which they had been erected or because they impeded other activity. There is no evidence of efforts to save them from destruction. But judging by the number of images alone, the fact and timing of the demolitions clearly interested artists and viewers alike. The images transformed the buildings into symbols of the pace of urban change; they also associated the buildings with the events that led to and followed their creation and demolition. Such images stimulated nuanced memories of the past that allowed viewers, through the collection and display of images, to comment on the events and their local impact. This essay considers how the fact of the buildings’ demolitions allowed the images to become potent symbols of physical and social separation.2

The analytical method I use in understanding this imagery applies the theory of collective memory developed by Maurice Halbwachs and later sociologists.3 Halbwachs emphasized the social dimension of memory, theorizing that people remember events, including those they have not directly experienced, as members of groups. Through the very act of remembering, they establish and re-establish the many, sometimes overlapping groups to which they belong.4 I argue that the images of demolished buildings discussed here were broadly accessible sites of collective memory. Viewing the images activated both personal and shared memories of the sites and the events associated with them. The stylistic and compositional features of the images framed those memories in ways that allowed viewers to associate themselves with particular groups, in these cases political and social “Amsterdam insiders.” The buildings’ positioning on the urban fringe gave the distinction of “insider” a spatial dimension. Viewers familiar with the site brought a wealth of personal experience to the viewing of the image. For such insiders, the image captured not just a single moment but local associations and knowledge, however biased or incomplete, of the site’s longer history.5

Demolition and Cityscapes

In general, very practical interests governed decisions to demolish buildings, such as the need to clear land for new development, enhance the flow of traffic, increase the availability of housing, and otherwise manage the urban infrastructure.6 The decision to produce or purchase an image of a demolished building could be driven by more emotional concerns. Albert Blankert has suggested that the impending demolition of a building provided an incentive for its representation, arguing that Johannes Vermeer only painted the buildings in the Little Street (fig. 3) when he learned they were under threat.7 Blankert’s suggestion, though later questioned,8 is based on the artist’s characteristically sensitive depiction of an everyday scene and the impression this gives the viewer of a personal connection between the artist and his subject. Style and sensitivity of depiction may be indicators of a link between an artist and a site (or indeed any subject), but they are limited indicators at best. Furthermore, such indicators say nothing of the connections to the site represented that a viewer of a cityscape might feel or come to feel. Popular literature, poetry, and governmental records, together with visual data from the images, can provide a more complete picture. Such documents, along with the cultural context provided by the buildings’ functions, their location on the urban boundary, and in particular their short life spans allow us to piece together some of the commonly held memories associated with these sites. It was these associations that led both artists and viewers to be interested in these images and which influenced the uses to which the images were put.

Landscape and cityscape images have long been associated by scholars with the broader cultural context of the period, but exactly how the relationship functioned is still a matter of debate.9 Seventeenth-century cityscapes in particular have been linked to textual descriptions of cities that express pride in the young nation and celebrate its rapid growth and economic success.10 Many of these texts are structured as walks around the urban fringe; indeed actually walking the city walls had long been a popular pastime for city dwellers, including artists.11 In a similar vein, sixteenth- and early-seventeenth-century landscape print series were organized and appreciated as “armchair” walks: tours of an area, usually the countryside, that could be taken from the comfort of one’s home.12 Images of the Heiligewegspoort and the blockhouses on the Amstel differ from most other cityscape images, however, in that they depict buildings that no longer existed.

Of course, these were not the only structures demolished or destroyed in the Dutch Republic during the seventeenth century. Amsterdam’s Old Town Hall was lost to fire in 1652, and much of Delft was destroyed when a gunpowder storage facility exploded in 1654. Many images of both survive.13 Intentional demolition was especially common along the fringes of cities, as urban expansion often required the clearing of wide swaths of land. Whether spectacular in the moment or more mundane, demolition and destruction had lasting implications for the lives of many people, and thus images of such events played a part in creating broadly accessible collective memories.

Some of these events exerted such an impact that the images are relatively easy to interpret today. The Amsterdam burgomasters purchased Pieter Saenredam’s painting of the Old Town Hall in 1658, six years after it was destroyed by fire, and hung it in the burgomasters’ chamber of the New Town Hall. Even without the documentary evidence, it would be easy to interpret the painting as commemorative, with its detailed inscription about the fire and its focus on the buildings themselves. In an undated drawing that Saenredam must have used in preparation for the painting, marginal notes indicate he researched the fire in a published description of Amsterdam.14 Egbert van der Poel painted approximately twenty versions of the aftermath of the Delft gunpowder explosion; all include the date of the event but were probably painted over many years.15 Although van der Poel’s stark cityscapes memorialize the widespread loss of life and property, they may have held a deep personal resonance for the artist as well: it is likely that he lost a child in the explosion.16

For events that were more controversial, or whose impact was political rather than physical, it can be extremely difficult to flesh out collective memories at a distance of more than three hundred years. We must rely, then, on clues provided by the visual imagery itself. For both the blockhouses and the Heiligewegspoort, the number of images relative to the importance and life spans of the buildings suggests there may be more beneath the surface than a casual viewing reveals.

The Blockhouses on the Amstel

In Hendrick Dubbels’s painting The Blockhouses on the Amstel (fig. 2), as in so many Dutch winter scenes, a cross section of society makes its way over a frozen canal, exhibiting a charming variety of skill on the ice. One couple with a child stands still at the center. The well-dressed man faces the viewer and the city of Amsterdam beyond. The woman puts her back to the city. She looks at the buildings centered directly over her companion’s head: two identical structures, each three stories high with a hipped roof, built along the Amstel river at Amsterdam’s edge in the summer of 1651.

While the painting at first appears to be a light-hearted depiction of winter amusements, the seventeenth-century viewer would have recognized the military function of the buildings. The blockhouses were designed to defend the city from river-borne invaders. The arched arcade running around the perimeter of each building concealed heavy artillery. From here soldiers could raise barriers across the river, and shooters could be positioned in the windows of the first floor, which also served as an armory and barracks. The troops stationed in the blockhouses were never engaged, however, and for reasons discussed below, the blockhouses were demolished in 1654, only three years after their construction. Their short life spans and the fact that they were never used in combat make nostalgia and even simple commemoration unlikely uses for the painting. Their military function also makes them an odd frame for a scene of fun on the ice, and indeed the couple and child at the center do not participate in any of the activities. Their poses, each gazing in a different direction, suggest comparison and questioning. But what is being compared? To answer this question, one must look into the circumstances surrounding the decisions to build and later demolish the blockhouses.

The blockhouses had been constructed as a direct result of the attempted invasion of the city by Willem II, prince of Orange, in the summer of 1650. The invasion failed and the troops eventually withdrew from the surrounding countryside. But the generous breadth of the Amstel river now stood out as a dangerous weakness. The addition of these defenses to the long-planned extension of the city walls seemed a sensible choice.17 Yet the blockhouses generated controversy even before they were built. Some merchants feared that they would impede commercial traffic on the river. The Vroedschap, Amsterdam’s town council, decided in March 1651 that a commission would be formed to investigate the potential problem and report back. The committee recommended only two days later that building should proceed.18 Construction finished that summer.

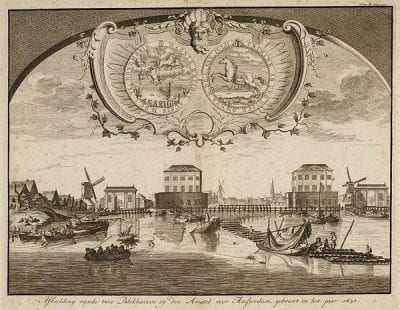

A print produced the same year by Pieter Nolpe and Jacob Esselens (fig. 4) suggests that the impact on river traffic was immediate and significant. The print presents the blockhouses as viewed from outside the city. Much activity takes place in front of them, but little of it has to do with commerce. A long row of pylons (a supplemental defense that was soon removed) curves from in front of the blockhouses to the foreground. A boat has been tied to one of the pylons and its occupants seem quite settled: they have erected a tent of sorts and hung some clothing to dry. Seven men in and around the boat converse. Ten figures are swimming or have just emerged from the water. On the western bank, in a boat filled with kegs, a man seems to be making their contents available to others nearby. A few commercial craft appear much closer to the blockhouses, and the strained poses and bent backs of their pilots indicate the effort of coping with the new obstacles. That the blockhouses came to be associated with the city government that ordered their construction should come as no surprise. Indeed the print gives credit to the Vroedschap in its caption: “Image of the two blockhouses on the Amstel before Amsterdam, built by order of the honorable burgomasters and thirty-six councilors of the same city, in the year 1650, engraved by Nolpe who prints and sells the same.”19 Yet the apparent admiration for the defense project is belied by the placement, just above the reference to the honorable burgomasters, of a favorite stock figure in Dutch art: the man who crouches off the side of the pylons and defecates into the river (fig. 4a). He is further emphasized in the print by his direct gaze out at the viewer.

The print is thus less a tribute to the wise rulers of the city than a censure of their decision. The Vroedschap records of the period indicate that several accidents resulted from the placement of the pylons.20 Caspar Commelin reported in 1693 that the piles driven in front of the blockhouses had been set densely enough to alter the flow of the Amstel and create dangerous shallows.21 Eventually the impediment to river traffic was judged too severe and the blockhouses were removed only three years after their construction. What had once been a logical choice to protect the city now seemed to be a foolish waste of funds. Commelin highlighted the irony in his 1693 description of the blockhouses: “They were then demolished and destroyed in July of 1654, through no other order and command than those of the above-mentioned Vroedschap of Amsterdam, at whose expense they had been built in the first place.”22

That the print is critical of local leaders and somewhat comical does not mean that it was viewed only behind closed doors. Another impression of the same print in the Amsterdam city archive has been hand colored, suggesting that it was viewed as an art object, albeit a relatively inexpensive one, and may have been hung on a wall.23 It is quite possible that the owner of the print, who went to the trouble of having it colored (probably by a professional colorist), was a merchant, who thus aligned himself with the city’s commercial interests. In any event, the print speaks in a relatively light-hearted way of an antagonism between merchants and those who would interfere with business. We will see later on that a form of this same tension played an even larger role in the creation and viewing of images of the blockhouses.

For viewers for whom the criticism expressed in the print was a little too blatant, Nolpe and Esselens provided a milder alternative. A second state of the print (fig. 5) retains the foreground figure who looks out at the viewer, but the caption’s reference to the Vroedschap has been wiped from the plate. It would appear that some viewers, rather than avoiding the image altogether, demanded a version that sidestepped the embarrassing issue of who had funded the blockhouses. Thus, representations of the blockhouses must have held some other attraction.

Compare these prints to another by Reiner Nooms of ca. 1654 (fig. 6), in which boats move swiftly between the blockhouses (here viewed from within the city) and guards stand watch atop the buildings. Unlike the Nolpe and Esselens prints, Nooms’s print implies no criticism. The caption reads: “The two Blockhouses on the Amstel outside Amsterdam,” with neither a textual reference to the Vroedschap nor any visual criticism. Nooms does, however, provide additional information. His caption continues: “Made in the Year 1651, Taken Down in the Year 1654.”24 The date—”den 2 July”—has been added to the impression now in the collection of the Amsterdam city archive, in ink in a seventeenth-century hand.25 This indicates that a viewer with a particular interest in their demolition was not satisfied with the artist’s indication of just the year but wanted to note the very day of the blockhouses’ removal. Nooms’s image was reproduced by both Jan Cralinge and Clement de Jonghe (fig. 7 and fig. 8), who also included the date of demolition.

We have reason to suspect that Nolpe and Esselens produced their prints well after the demolition, as they incorrectly specify the year of construction as 1650, thus indicating a continuing demand for images of the blockhouses. Further evidence of this continuing demand is provided by the fact that the depictions of the buildings themselves vary quite a bit from image to image, suggesting that artists created their works using other images as sources rather than the buildings themselves. For example, in Dubbels’s painting, the upper stories of the buildings appear rather low in comparison to the height of the water-level gun ports, while in the Nolpe and Esselens prints the buildings have taller proportions and the first-floor parapet created by the gun ports is narrower. Also varying from image to image is the width of the Amstel at this location. In a drawing by Roelant Roghman (fig. 9) the river appears quite wide.

Two questions are raised by these images. First, what was it that interested artists and their audiences enough to continue producing and viewing images of these structures after their demolition, structures that could fairly be dubbed “mosterd na de maaltijd” (mustard after the mealtime), having been built only after the direct threat had passed and then proving to be an absolute nuisance for three years? Second, what about them made the fact of their demolition so important?

The situation becomes clearer if we look at a medal the city issued after Willem II’s death on November 6, 1650, only a few months after his failed invasion attempt (fig. 10). The medal by Sebastian Dadler shows on its obverse a rearing horse, surrounded by a quotation from Virgil, which reads in translation, “From one crime they may learn all,” and the date of the invasion attempt.26 Behind the horse is a view of the blockhouses quite similar to that seen in the paintings and prints discussed thus far. The medal goes beyond the humor of the prints, however, to express outright defiance of authority. The fact of the medal’s striking itself, a celebration of the death of the young Republic’s stadholder, indicates the severity of the bad feelings between some in Amsterdam and the house of Orange. The choice of the motif of the blockhouses to represent Amsterdam is not surprising, as they were built in response to Willem’s invasion attempt. But the blockhouses were by no means the only or even the most obvious choice to represent Amsterdam. Artists depicted the city from the IJ-side far more often; indeed before 1650, images of the Amstel-side of the city are rare.27 As new structures, likely unfamiliar to many outside of Amsterdam, the choice of the blockhouses implies that the medal was meant specifically for a local audience.

The role played by the blockhouses in the relationship between Amsterdam and the Orange family is made clearer still in a pamphlet titled “Nicknames of the Blockhouses of Amsterdam.” The pamphlet reads:

These are the houses, that like shields, and helmets,

protect the City from a bellowing Tyrant:

he set out, as he pleased, with Marauders, Murderers, Villains,

And all manner of horrors in tow. The brave stood firm.

What name is best given to these virtuous Brothers?

The one lord of Englenburgh and the other lord of Swieten.28

The nicknames that the unknown author cites as best for the “virtuous Brothers,” lord of Englenburgh and lord of Swieten, refer to the Bicker brothers, Andries and Cornelis, members of the Vroedschap and powerful opponents of the prince of Orange. In order to understand the significance of the symbolism, we must move back a few years into the earlier history of dealings between the Bickers and Prince Willem II.

The Bickers’ relationship with the prince grew difficult after the death of Willem’s father, Frederick Hendrick in 1647 and the end of the Eighty Years’ War in 1648. The end of the war put Willem in a difficult position. His father’s role as leader of the army had been clear. Willem, however, stood at the head of an army facing a lasting peace. Frederick Hendrick had urged the maintenance of a standing army of 39,000 men after the war for defense. The States of Holland, represented by Andries Bicker, among others, wanted a force no greater than 26,000. Repeated negotiations and compromises brought the army down to 29,250 men by 1649. At this point, both sides dug in their heels, neither willing to compromise further. Each side found compelling reasons for its position. The new prince of Orange argued that the Republic, significantly larger than it was in 1609 at the declaration of the Twelve Years’ Truce (which effectively, if not officially, ended the war), needed the troops for defense of its outer territories.29 The States of Holland argued that the monies going to pay the army could be better spent reducing the nation’s debt, then being financed by interest payments of six million guilders per year.30

The prince and the city of Amsterdam also disagreed about the limits of each party’s authority, a dispute that threatened the very existence of the Republic. Willem longed for the opportunity to prove himself in battle; his familial ties to Stuart England (Charles I was his father-in-law and Charles II, still in exile, his brother-in-law) and the long-held grudges against Spain provided ample further motivation for military action.31 If Willem had had his way, the country could have been dragged back into war. Amsterdam balked not only at the expense of the army but at the proportion its citizens needed to pay. Amsterdam alone funded just under 30 percent of the total cost of the Republic’s army.32 Payments to the army were not made through a central authority, but rather through companies that were put in the pay of cities. Amsterdam’s Vroedschap, led by the Bickers and their followers, felt justified in dismissing the companies it paid in June 1650. These soldiers, they argued, were in the city’s employ and could thus be disbanded on the city’s authority. Herein lay the real challenge for the country. Prince Willem had been able to muster enough support to ensure that a vote in the States General, the central governing body of the Republic, maintained the army at its then-current level. In the following weeks, Amsterdam acted on its own, under the leadership of the Bickers and their supporters. The city had gone around the States General, threatening the fragile ties that held the body together. Amsterdam maintained that decisions made in the States General had to be unanimous rather than made by majority. Thus antagonism between the city and the prince had snowballed into an issue that jeopardized the structure of the Republic itself.

Amsterdam’s dismissal of the troops gave Willem the final justification he had been waiting for since at least the previous winter. He assembled a force under the command of his cousin and long-time source of encouragement in this matter, Count Willem-Frederick of Nassau. While the troops marched on Amsterdam, Willem explained the necessity for action at the States General in The Hague.

The event itself could not have gone worse for Willem. Willem-Frederick’s small force arrived on time, but troops from Orangist Arnhem and Nijmegen lost their way in a dense fog. They were passed in the night by a messenger more familiar with the route. Upon the messenger’s arrival in Amsterdam, he alerted Cornelis Bicker. Bicker called the militias to the walls and ordered the closing of the gates and destruction of key bridges. When the united force finally arrived, rather than beginning an invasion it faced a stand-off. The embarrassment for Willem was so great, according to a pamphleteer, that when he received word of the invasion’s failure he jumped upon his table and trampled the notice underfoot.33

Although hardly a clear success for Willem, the attack did gain him some bargaining power. Amsterdam did not receive the help it hoped for from other cities and was loathe to prolong a conflict that could shatter the delicate framework of trust and stability on which its economic success depended. Willem, searching for some measure of vindication, focused his attention on his most vocal opponents in the city: Cornelis Bicker and his brother and fellow burgomaster, Andries. Many in the city, especially the faction led by Cornelis de Graeff and Joan Huydecoper, considered the Bickers too powerful and influential and, although they were opposed to allowing the prince to select the local government, they were only too happy to see the Bickers go. The brothers finally resigned when their lack of support became apparent. Satisfied with this minor victory, Willem’s forces withdrew.

Shortly afterward, the city, now keen to ensure the protection of such a tempting route for military action, voted to build the blockhouses to close the wide gap in its defenses. The decision to build the blockhouses may have sent another message, as well. While Willem argued for defense through manpower, Amsterdam pursued a course more in keeping with its own culture and values: it built. Utterly modern and stylish, the blockhouses served much like a city gate. They presented an image of the city as it wished to be seen: resourceful, attractive, and strong. Furthermore, the strength was achieved not through more soldiers but through the efficient deployment of a small force properly equipped; by their very existence the blockhouses continued the argument over the issue of troop levels.

Supporters of the Bickers would not let the matter lie resolved, however. Few other issues or events in the preceding fifty years led to the publication of as many pamphlets.34 Some called for the restoration of the Bickers,35 others simply lauded their virtue and courage.36 For their part, the Bickers’ opponents made their voices heard as well. The sheer number of pamphlets is commented upon in yet another pamphlet in one of the period’s favorite formats, “A conversation between three Amsterdammers, called Claes, Jan and Dirck, on the question of their Lords the Bickers.”37 Over the course of several pages, the three title characters marvel at the number of pamphlets and the far-flung locations in which they can be purchased, and compare incredulously the things they have read. No pamphlet should be taken as truth. Their intention to persuade was as well known in the early modern period as it is today. Their number and their variety of tone indicate nonetheless the widespread interest, both geographically and socially, in this controversy. Everyone seems to have taken a side.

The brief text directly linking the Bickers and the blockhouses is one of the milder offerings among the many that circulated in these years. The situation became heated enough that in 1651 the States General finally forbade pamphlets that insulted any domestic or foreign authority. Repeated bans and prosecutions reveal that the prohibition had limited success.38 The production, circulation, and viewing of images of the blockhouses, then, were likely more than a simple assertion of Amsterdam’s independent streak. Although the images avoided overt political commentary and thus evaded the States’ General ban, they were nevertheless a politically charged statement of support for the Bickers and their position against the prince of Orange. The ban even provides a likely motive for the second state of Nolpe’s and Esselens’s print, in which the reference to the agency of Amsterdam’s government in building the blockhouses, and thus in opposing the prince, was removed.

The physical fate of the blockhouses themselves made them particularly suitable symbols for the political fate of the Bicker brothers. The blockhouses’ classicizing facades linked them stylistically with the rapidly growing city, just as the Bickers were associated with the city’s power and influence through their positions on the Vroedschap. The two buildings stood at the vanguard of the city’s defenses, protecting the city’s (physical and political) insiders and defining the “outsider” by their position and function, just as the two brothers stood at the head of Amsterdam’s opposition to an outsider, Willem II. The manner in which the blockhouses were so often depicted in the prints—centrally positioned, towering over the distant city skyline and the small boats below, and viewed so as to silhouette their massive forms against a broad sky—lent the blockhouses a magnificence and by extension pictured the Bickers as tragic heroes.

Most pointedly, the buildings were demolished just as the Bickers were finally removed from office. Ultimately, neither the blockhouses nor the Bickers could withstand the controversy they created. The buildings would have been far less powerful symbols of the two brothers had they remained standing. For the Bicker supporters, the brief life of the buildings and their removal by those who asserted that they brought more trouble than protection must have functioned as an evocative metaphor for the careers of Andries and Cornelis Bicker.

A much later print by Bernard Picart reveals the persistence of the relationship (fig. 11). Picart revisited Nolpe’s and Esselens’s depiction of the blockhouses but added Dadler’s medal within an elaborate cartouche at the top of the print. Picart had settled in the Republic in 1709–10.39 In 1711, Johan Willem Friso, the chosen heir of Willem III, died, marking a key moment in the second stadholderless period.40 The print likely celebrates, as the medal had done two generations earlier, the death of a member of the house of Orange as a victory for Amsterdam.

The demolition of the blockhouses resonated with memories of the truncated careers of the Bickers. Paintings, drawings, and especially prints, appearing in many versions over the years, kept these memories of the blockhouses and the Bickers active in the minds of viewers long after both had lost their original roles. The variety of inscriptions on the prints (although many had no inscription at all), further suggests that a range of viewpoints on the political issue could be accommodated by the images, from overt support for the Bickers and anger toward the prince of Orange to more moderate discomfort with the prince’s actions. The popularity of the images may have even extended beyond those with strong political views to people who simply came to regard the images as an attractive and typical view of the city. No Amsterdam viewer would have been unaware, however, of the story of the invasion and the commonly held view of Willem II as an outsider.

The Heiligewegspoort

Images could also define urban insiders, as was the case at another site of demolition at the urban fringe. Here images gave owners and viewers a means of expressing their knowledge of and attachment to a landmark lost to redevelopment. The Heiligewegspoort was one of a handful of gates along Amsterdam’s edge rebuilt in the seventeenth century, the existing wooden structure being replaced by a stone gate in 1636. The gate stood on the present-day Koningsplein, where the Leidsestraat and the Heiligeweg met between the Singel and Herengracht canals, as seen in a map of 1625 (fig. 12).41 Its wooden predecessor had stood on the site from about 1597. The stone gate was demolished in 1664 as part of the fourth expansion of Amsterdam. Although only a replacement of an existing building, the 1636 gate signaled an important change. Before the Heiligewegspoort, gates in Amsterdam included the massive corner towers typical of medieval design. They also incorporated defensive design features, such as a layout that required those passing through the gate to make one or more turns. Visitors entering the Harlemmerpoort, for example, turned both on the bridge before the gate and again within the gate structure. A narrow, straight path passed through the Heiligewegspoort, making it the first gate in the city whose functions were primarily passageway and beautification rather than defense.42

The city commissioned its design from Jacob van Campen, a young painter-architect working in the classicizing style just becoming fashionable among aristocrats, wealthy bureaucrats, and merchants in the United Provinces. The Heiligewegspoort featured a symmetrical design, with a classicizing pediment over the central passage, with niches to either side topped by carved swags. Ionic pilasters framed the bays, and urns on the roof served as chimney pots. This was van Campen’s first completed work in Amsterdam, hinting at the success that would culminate in his design for the new Town Hall a little over twenty years later. Van Campen’s gate design was thus quite different in its forms and scale from the earlier gates.

Gates and urban defenses appear in many images from the period, conveying ideas about military and economic power and physical growth, along with narratives of urban history.43 The numerous city descriptions written in the seventeenth century, such as Olfert Dapper’s Historische beschrijvinge van Amsterdam of 1663, catalogue gates among the city’s important monuments. The popularity of Heiligewegspoort imagery in particular is evidenced by its appearance in ten known paintings, including two works by Abraham Beerstraten and several by Jan van Kessel and his followers, as well as at least a dozen prints and drawings.44 The gate is shown from a variety of viewpoints both outside and within the city, as in a painting by Gerrit Lundens (fig. 13), and there are slight variations in the building’s proportions and its position within the surrounding landscape. These variations suggest that at least some of the images may have been made by artists who had not seen the gate.

The gate’s attractive appearance must have accounted in part for the interest it held for artists and viewers, but its location likely played a role as well. The Heiligewegspoort, like all gates, marked the border between the city and its surroundings. Nevertheless, this particular border was both physically and temporally awkward. The third expansion of Amsterdam, carried out from 1610 to 1615, ended at the Heilgewegspoort. The gate stood in the crook of an “elbow” formed by a sharp turn in the city wall, a spot extremely difficult to defend. The long expanse of wall along the Overtoomsevaart outside the gate could not be covered by fire from either end.45 Indeed, the Heiligewegspoort, with its triumphal arch design, was not well suited to providing fire cover or even preventing access to the city. The design features that made it so fashionable also meant that it lacked all of the defensive features of earlier gates. Its steep roof and windowless exterior, for example, provided no platforms on which to position shooters in the event of attack. Finally, the completion of the fourth expansion left the gate well within the city. Its obsolescence was implied by the very site of its construction.

The Heiligewegspoort thus marked the pace of change in the city in a unique way. Its contemporary style was an early example of the classicizing architecture that would dominate Amsterdam’s finest buildings and neighborhoods for the next several decades. Yet in spite of its attractive appearance, the gate did not survive the expansion whose style it heralded. The gate was demolished only twenty-eight years after its reconstruction.

Several of the images of the gate, especially paintings, suggest both a celebration of classicizing style and the rapid pace of change. Three of these paintings depict the Heiligewegspoort from inside the city.46 Abraham Beerstraten’s two paintings view the gate from the northeast and northwest (fig. 14 and fig. 15, respectively). Each places the gate slightly off-center, with the view from the northwest including the double-span drawbridge and the fore gate over the canal and the view from the northeast including in the background the houses built by Philips Vingboons for Jacob Cromhout, completed in 1662.47 The painting by Lundens also presents the gate from the northeast, in this case the location of a festive and crowded fair. Each of the paintings pays close attention to the architectural detail of the gate, but even here differences are readily spotted. The attic storey in Lundens’s painting is much taller than in either of Beerstraten’s, especially the view from the northwest. The sculptural relief in the central pediment, clearly a ship in Beerstraten’s view from the northwest, is difficult to read but appears to be different in the other two paintings.48

The gate was painted many times from outside the city, as well, most of these being versions of a painting by Jan van Kessel (fig. 16).49 These all show the gate from the southeast, in a view very similar to that taken in Jan Beerstraten’s painting of the gate in the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin (fig. 1), discussed above. Their number (five painted examples survive) and the variations in quality and size suggest a rather diverse market for images of the gate.

All of the paintings monumentalize the gate, with artists often choosing a perspective that allows the viewer to look up at it, as for example in the Jan Beerstraten painting and in Lundens’s view (fig. 13). Although the gate is clearly the focus of the images, all present it within a setting of surrounding streets and buildings, so that its situation within the city of Amsterdam is made absolutely clear. The viewpoint is not unlike that taken in many paintings of the New Town Hall, and the dramatically clouded skies in most of the paintings suggest a memorializing of the gate. The attention to (often inconsistent) detail and indeed the date on the Dublin painting all indicate that interest in the Heiligewegspoort persisted for some time after it was demolished.

The Abraham Beerstraten view from the northeast (fig. 14) further suggests the shape of things to come through the inclusion of the new houses along the Herengracht. All of the paintings celebrate the fast pace and chic style of the changes underway in Amsterdam. As relatively large works executed in oils, they were probably intended for an audience very like the people buying the new homes along the expanded canals, that is, those likely to equate change with progress. Recognizing such a painting’s subject would have shown that the viewer understood both Amsterdam’s recent past and the path of its present development. Remembering that the Heiligewegspoort had been built in a fashionable style only to be taken down for yet more extravagant construction identified the viewer as an insider, established in this wealthy new area of the city and very familiar with its past. Even a newcomer to the city who had not seen the Heiligewegspoort or its demolition could proclaim insider status for himself through owning, viewing, and understanding the image.

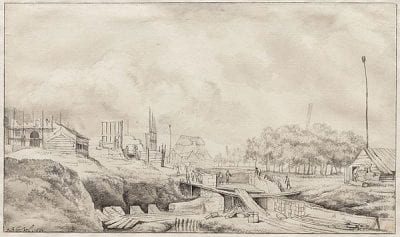

Not all images of the gate viewed the situation so positively. Jan van Kessel, the same artist who produced two paintings that monumentalize the gate, also produced two remarkable drawings now in the Amsterdam city archive that bring the gate down to a very human scale. Each drawing shows a stage in the demolition of the Heiligewegspoort. In the first (fig. 17), the gate has been disassembled to a bit below the roof line. In the foreground the infill work has begun to create the Koningsplein. In the second drawing (fig. 18) work has progressed further. The infill is complete, and still less of the gate remains, just left of center.

In these drawings, we witness the muddy mess of urban expansion. Van Kessel leaves the viewer in the most uncomfortable and troubling stage of a change: at its midpoint. He depicts the stage of demolition when the familiar has been stripped away and the promised improvements are still very far from realization. The viewer is left, like the two tiny figures in the center of the view looking west, in a place at once familiar and unfamiliar. Isolated within too much open space for a city as large and bustling as Amsterdam, the figures are pointing and comparing observations and trying to orient themselves within these new surroundings.

Viewers of such images, like the figures in them, enact a mental walk, retracing the areas depicted at different points in time. Walking along the city walls was a favorite pastime in the seventeenth century.50 Michel de Certeau has argued that it was through such walking practices that the complexity of the city is organized and walkers orient themselves in the familiar yet strange surroundings.51 A long tradition existed in the Low Countries of landscape print series, city descriptions, and poems structured as walks.52 Viewing an image became a substitute for actually moving through the space depicted. Through viewing, beholders regained an element of control over their environment by observing the spatial boundary between the city and its surroundings, a control lost in expansion. Growth removed the oddly shaped border area in this part of the city, but in moving it changed many people’s physical relationship to the border and thus that part of their sense of identity with the city that depended on that border. Physical insiders became physical outsiders as homes and businesses were demolished. The evidence of their connections to the old border area was swept away with the rebuilding and expansion.

A person’s physical location inside the city was an important factor in establishing him or herself as a social insider, as well. When this status was lost, for example by forced relocation to make way for expansion, that social standing could disappear along with a residence.53 Images allow viewers to maintain the status of insider in another sense, as that of persons with knowledge or memory of an area before its transformation. A characteristic of landscape, as described by Dennis Cosgrove, applies to cityscape as well: viewers hold an important control over their relationship to the scene in that they can turn away from the representation and view it no longer. Actual insiders, however, cannot turn away. Their knowledge and experience of the place represented do not permit the same detachment.54 In the case of the Heiligewegspoort and other demolished buildings, it was rather the local authorities who, through urban development, had made the city unfamiliar to the viewer. The images provided a means of maintaining and reclaiming a connection to the lost border area. Possessing such an image implied that owners had the experience of the area necessary to understand and recognize its subject and they could connect that subject to experience over time.

Indeed, these images conferred a special status on viewers because they connected them to an experience that is no longer available. If, as Anja Kervanto Nevanlinna argues, “to demolish a building or part of a city is to erase…unrecoverable histories of particular meanings,”55 then to record such sites in images is to keep the site’s existence active in the present. To view the drawings and to undertake the mental walk is to carefully examine the representation in relation to experience, to actively recognize the sites depicted, to connect the images into a series covering time and space, and with repeated viewing, to replicate the process over time.

Depictions of demolitions like that of the Heiligewegspoort can also be productively compared to another popular theme in seventeenth-century art, the ruin. Both the demolished building and the ruin are disused structures; the differences lie in the length of time over which the physical change occurs and the agency of humans in the deterioration process. Susan Donahue Kuretsky has written of images of ruins that they “focus directly and analytically on the actual processes that shape and alter the physical world”,56 that they reflect on “the tenacity of human works,” and that ruins themselves are “subversions of planning and order.”57 Images of demolished buildings provide a counterpoint to the images of ruins that Kuretsky analyzes so insightfully. In the case of demolished buildings, the tenacity of human works falls to the greater human will to shape the urban environment. They indeed consider the process of change, but a change that happens quickly and can be carried out with all the violence of natural disaster. Here it is the image itself that counteracts planning and order by refusing to allow the erasure of the building. The existence of the images should not be taken to imply a desire to impede the expansion taking place in Amsterdam but rather as representing an interest in active analysis of and comparison to the viewer’s physical surroundings. The images focus on the altered urban streetscape, in addition to the process by which it was altered. The comparison of old and new and an analysis of the impact of change were expressed in a poem published by Sijbrand Feitama, Sr., in his 1684 collection titled Christelijke en Stigtelijke Rijm-Oeffeningen. In the opening lines of his remembrance of the area around the gate, Feitama compares the sites that have been lost, including the Heiligewegspoort, to their new replacements:

Whenever I walk along the old canal

That is now named after newer lords,

I cannot help but observe,

How everything can change:

So I consider in my mind,

The state of old affairs,

With the first evil from the beginning,

And what men make.

I see here the area of the Holy Way,

And the cemetery, just outside

The Gate, so I think, and I say:

Where will the growth stop?

I find it rather good,

but little, to my mind;

Here was the wall of the Old City

And the Canal to the center,

And the little sluice with its sole arch,

Through which one could row out,

the field appeared quite high,

Because the ascent was exhausting etc.58

Feitama’s tone expresses a strong sense of ambivalence about growth and change. He speaks as an insider and looks back in time rather than around him at the new construction. The senses of memory and identity that find a visual expression in the images have a verbal counterpart in Feitama’s poem. It is Feitama’s experience of the gate’s past that lends authority to his commentary on its present. His evocation of the past gives the thought-process of the poem a duration that it would otherwise lack. His thoughts are based on much time spent in the area, careful observation, and yet more careful thought about its present and future.

The figures in Van Kessel’s drawing of the gate’s demolition (fig. 18) model this same behavior of active memory recall. Their position by the gate, their surveying of the open space, and the gesture of pointing all indicate a process of evaluation; that is to say, an analytical comparison of past to present. The location of the gate at the urban fringe contributed to the appreciation of change and movement. Gates provided the specific controlled passages to the center at times and locations chosen by the local government. Their physical presence and defensive function combined to impart a ritual quality to a resident’s, or an “insider’s,” passage through the gate. The in-between space of the gate itself, neither wholly within nor without the city, marks the individual’s return to the familiar. The passage was repeated at each journey out, and at each return. The acts of passing through the gate and walking along the familiar streets recreate the individual’s association with the area each time they are performed. This would have been true for any gate in the city. In the case of the Heiligewegspoort, as I have shown, additional factors were at work. Its thoroughly modern style and removal after only twenty-eight years made it a particularly poignant symbol of the rapid pace of change taking place in Amsterdam.

One might assume, given the derelict appearance of the gate in these two images, that these were the last to depict the Heiligewegspoort. The Dublin painting proves this is not the case. The gate continued to be represented in the following years, as well. It appears in a gable stone (fig. 19) used in a house built on the corner of the Koningsplein in 1668.59 The stone accompanying the carving of the gate records its date of demolition, but not the year of its construction; the change, as much as the building itself, is being marked. The house with the gable stones in place appears in a drawing by Reinier Vinkeles of 1764 (fig. 20).

The cases of the Heiligewegspoort and the blockhouses on the Amstel demonstrate that people in the seventeenth century held on to their memories of and associations with parts of the city well after those areas had changed. Sites along the city’s border were particularly suggestive because they changed the physical definition of the city, and thus the viewer’s relationship to the urban complex. Demolition removed the physical traces of buildings and other structures, but the act of demolition, as seen in these cases, actually strengthened memories of the sites and made them more resonant. To use Riegl’s words, images transformed the sites into “unintentional monuments”: structures that became monuments by virtue of a status given them long after they had ceased to serve their original purpose.60 Yet since no physical remains of the blockhouses and the Heiligewegspoort existed, their destruction after so little time, rather than their endurance, contributed to their status as (pictured) monuments.

The very quotidian quality of the structures enabled them to serve as rich carriers of collective memory. Unlike intentional monuments, they were not built to commemorate overtly a specific event or person. Unlike widely admired buildings on the grand scale of Amsterdam’s new Town Hall or its Stock Exchange, they generated no fanfare at construction nor did they remain as permanent fixtures of the cityscape. In the two cases studied here, the relatively commonplace structures and short physical histories left nearly blank slates on which artists and viewers could write their own interpretations of the past.

Although the blockhouses were built in response to a specific event, their demolition created an opportunity to criticize the decisions of local government as wasteful folly or to condemn national leaders as treacherous. In the case of the Heiligewegspoort, its demolition drove people from their homes and businesses, separating them from familiar neighborhoods and associations, and created the opportunity for others to inhabit fashionable and luxurious new homes. Images of these sites forced reconsideration of what part knowledge of the city’s past forms could play in defining social roles. In more practical terms, this study demonstrates that it may be more fruitful in many cases to investigate the local, specific associations with a small group of images rather than to identify a single meaning or theme by which to interpret a genre. Ultimately, images of demolished buildings in particular force us as art historians to reconsider our all-too-easy reliance on the construction history of a building to date a topographic image. Interest in these sites persisted well after they were erased by the relentless pressure of the city’s expanding borders.