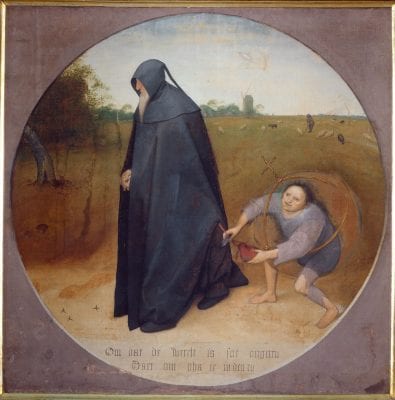

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Peasant and Nestrobber (1568) remains one of his most challenging paintings. By the time of its creation Bruegel had already innovated by treating ordinary people as subjects suitable for the attention of a serious painter. In this study it is proposed that in Peasant and Nestrobber Bruegel was engaged with the troubles of his time, drawing on a popular German satire and the language used in religious controversies to create a scene of daily life in which the artist acted as both witness and commentator.

Small in size and relatively uncomplicated Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Peasant and Nestrobber of 1568 remains one of his most enigmatic paintings (fig. 1). There is little agreement about its genesis, its interpretation, or its relation to Bruegel’s other works, including his mysterious drawing The Beekeepers. One of the most intriguing aspects of Bruegel’s art is its ability to involve the viewer, raise questions, and hold attention. In this study it is proposed that the enduring fascination of Peasant and Nestrobber is due in part to Bruegel’s efforts to engage with the troubles of his time, an aspect of his art that has received less attention than it warrants.1 In his earlier works Bruegel had innovated by treating ordinary people as suitable subjects for the attentions of a serious artist.2 In Peasant and Nestrobber the ordinary becomes a vehicle for criticism, a development important for the history of genre painting, and one that provides an insight into the staying power of Bruegel’s art. Contemporary events were normally the province of the anonymous artists and writers who flooded the Low Countries with pamphlets and derogatory images.3 Instead of ignoring the animosities created by the Reformation, the harsh governmental repression of heresy, and the devastating power struggles that were precipitating a virtual breakdown of the social order Bruegel made it part of his creative process, acting as both witness and commentator.4 The viewer needs to know little about the time and place in which his works were created to find Bruegel’s art engrossing, but part of their interest results from the ingenuity of an intelligent and gifted artist trying to express his views under extraordinarily difficult conditions.

The Problem

Bruegel’s Peasant and Nestrobber should present few problems of interpretation. Signed and dated by the artist, “Bruegel MD. LXVIII,” the painting on wood panel is small in size (59.3 x 68.3 cm) compared to larger works such as his Battle Between Carnival and Lent (118 x 165 cm), and the composition is relatively uncomplicated. It is the first painting to feature someone robbing a bird’s nest, but it has a visual precedent — a woodcut with a nestrobber falling from a tree in Sebastian Brant’s popular Narrenschiff (Ship of Fools) (fig. 2). Bruegel’s late drawing The Beekeepers is also relevant as it includes a man in a tree and handwritten lines that refer to the robbing of a nest (fig. 3). Yet, as Manfred Sellink observed, in his compilation of the artist’s works, Peasant and Nestrobber and the related drawing “have raised more questions in the minds of scholars and connoisseurs than almost any other works by Bruegel.”5

Bruegel’s ability to raise questions and create a satisfying visual experience even in a composition as relatively simple as Peasant and Nestrobber accounts for the many interpretations it has engendered as well as the lack of agreement. There are only two figures, the setting is rural and their clothing identifies them as peasants. The heavy-set man in the center carries a large stick and has a knife case and horn hanging from his belt. As he strides toward the viewer he glances to his right and points at the second man, who hangs precariously from the branch of a tree, his hat falling behind him as he reaches for the eggs in a bird’s nest. Farm buildings are visible in the distance and on the right there is an expanse of water with a twisted pollard tree hanging over it, the curve of the tree repeated by a sack lying on the ground nearby. The realization that the water extends across the foreground and the peasant is about to fall into it usually comes late in the viewing process, a delay in perception that complicates the viewing experience and creates a sense of tension as the viewer anticipates the man’s imminent fall. One foot is already over the edge of the bank and as he steps forward the weight of his body will propel him into the water. Bruegel included all the visual information needed to predict the outcome, but the actual event is left to the viewer’s imagination.

In 1568 Bruegel’s viewers could recognize Peasant and Nestrobber as a “peasant” subject but it was not one with which they were familiar, such as a peasant dance or a peasant wedding. In its originality Peasant and Nestrobber is comparable to the series of paintings Bruegel produced between 1559 and 1563, the innovative period that ended with the artist’s shift to subjects his viewers could readily identify.6 Like those earlier works Peasant and Nestrobber has presented a challenge for art historians. Gustave Glück recognized the similarity between Bruegel’s Peasant and Nestrobber and the woodcut in Sebastian Brant’s Narrenschiff and concluded that the painting was about being presumptuous or obstinate, the title of the chapter it illustrates7 — an interpretation rejected by Roger Marijnissen because it “does not explain in the least” the presence of the “second peasant.”8

Interpretations that include the peasant striding forward tend to focus on stylistic issues with little attention paid to the role of the nestrobber. Charles de Tolnay and others have drawn attention to the way his pose relates to Italian models. For Todd Richardson the peasant’s arm pointing toward the robber is similar to the pose of Saint John as he appears in contemporary representations influenced by Leonardo da Vinci.9 Italian influence is also significant for David Levine, who relates the peasant’s sinuous pose to one of Michelangelo’s putti from the Sistine ceiling and sees the painting as a “form of parody aimed at both deflation and ridicule of illustrious models.”10

Other interpretations tend to view the peasants and certain details in the painting as representations of abstract ideas. Pierre Vincken and Lucy Schlüter describe Peasant and Nestrobber as a memento mori, citing a poem by Anna Bijns and interpreting many details symbolically — the theft of the nest represents death, for example, and the brambles on the left the precariousness of life.11 Pursuing a similar course Kjell Boström gave the flowers and plants symbolic value and proposed that the painting involves multiple oppositions, such as activity versus passivity and prudence versus stupidity.12 Ethan Matt Kavaler has suggested that Peasant and Nestrobber “implies ethical systems in conflict,” and he relates it to The Beekeepers, with its “representation of a communal ethic opposed to individual enterprise.”13 If none of these interpretations have produced a consensus it is due to the difficulty of demonstrating why one abstract idea is more salient than any other.

The problems presented by Peasant and Nestrobber are further complicated by The Beekeepers (fig. 3). The drawing is signed “BRUEGEL MDLXV,” and while the date is not entirely legible it is generally assumed it was made close in time to Peasant and Nestrobber.14 Three beekeepers dominate the composition, their faces hidden by protective hooded garments. On the right a man climbs a tree and in the lower left corner there are three lines of text: “He who knows where the nest is has the knowledge, he who robs it has the nest.”15 Whether autograph or not these lines remain enigmatic since there is no obvious connection between beekeeping and the robbing of a nest and the activity of the man in the tree is far from clear. Jan Grauls cited a proverb from Goedthals 1568 proverb book, but it refers to amorous affairs, a context at odds with both the activity of beekeeping and the robbing of a nest.16 Instead of making Peasant and Nestrobber more comprehensible The Beekeepers creates additional difficulties. The only area in which there is general agreement is that Bruegel’s Peasant and Nestrobber is not just a clever visual joke, an amusing look at peasant life, or simply an occasion for the artist to display his prodigious skills. Something more is involved.

Peasant and Nestrobber

When Gustav Glück identified the woodcut in Sebastian Brant’s Narrenschiff as Bruegel’s source for Peasant and Nestrobber he failed to note that the chapter it illustrates includes not one but two examples of being headstrong and certain you are right. The thirty-sixth chapter begins with the nestrobber who overreaches and climbs too high, but then refers to a second fool, the fool who “goes off the right road (Der irrt gar oft auf ebnem Wege).” This fool is in as much trouble as the first. He “finds no road to lead him home, falls and is alone (Auf denen Heimkehr nicht wird sein / Weh dem, der fällt und ist allein!).” To emphasize both examples of being presumptuous Brant repeats them.

A fool may tumble painfully

Who climbs for nests upon a tree

Or seeks a road where none is found.

[Die suchten Weg, wo’s keinen gab

Und steigen Vogelnestern nach].17

Sebastian Brant gives as much attention to the fool who misses the road as he does to the nestrobber. Bruegel does the same.18 The walking peasant occupies the central place in the composition and while his red pants draw attention to the nestrobber it is the walker’s pointing finger and upward glance that insure the viewer will note the climber as he clings to the tree, his precarious position emphasized by the hat falling from his head. The nestrobber has climbed too high and is danger of falling, but the situation for the peasant who observes him is equally perilous. He has missed the right road and his next step will send him into the water. The text of the thirty-sixth chapter of Sebastian Brant’s Narrenschiff accounts for both protagonists in Peasant and Nestrobber and identifies them as warnings about being headstrong and obstinate, sure you are right when you are headed for disaster.

Bruegel’s adaptation of Sebastian Brant’s Narrenschiff is not surprising. It was one of the most innovative and influential books of the sixteenth century, the combination of text and illustrations making it a volume of special interest to artists. Brant was responsible for a number of scholarly works, including an edition of Virgil’s Aeneid, but the Narrenschiff was intended for a wider audience and is written in the vernacular, drawing on proverbs and popular culture as well as biblical and classical sources. First published in German in 1494, then disseminated throughout the north in Latin — Locher’s version in 1498 and Marnef’s in 1499 — it was followed by a number of vernacular adaptations. In some of these versions the woodcut of the nestrobber is used to illustrate a completely different subject. In Der zotten ende der Narren Scip, the Netherlandish version published by Guy Marchant at Paris in 1500,19 the nestrobber accompanies chapter 109 where the subject is fortune and the vagaries of chance, a chapter that includes a famous quote from Juvenal’s Satires (X, 365–66).20In other versions chapter thirty-six is omitted entirely. In his study of Der zotten ende der Narren Scip, J. R. Sinnema indicates it is based on Locher’s Stultiferae Navis and notes that “a characteristic of the Latin is the omission of chapter 36.”21 In spite of the availability of a Netherlandish text Bruegel relied on the German original.22

The close attention Bruegel paid to Brant’s thirty-sixth chapter and the care he devoted to making the two figures, and their activities and relationship, clear can be seen by comparing the painting with two later works, a seventeenth-century drawing by David Vinckboons that features a nestrobber (fig. 4) and a copy of Peasant and Nestrobber made by Bruegel’s son, Pieter Brueghel the Younger (fig. 5).23 In Vinckboons’s drawing the joke is obvious — one of the men pointing at the nestrobber is being relieved of his money bag — and rather than clinging to the branch of the tree the nestrobber is safely ensconced on top of it. In Brueghel the Younger’s copy the landscape is expanded on both sides, a change that probably reflects the interests of a seventeenth-century audience, but one that detracts from the principal figures and disrupts the compact organization of the original, including the diagonal that extends from the nestrobber through the pointing finger of the peasant to the twisted tree hanging over the water.24 In addition, Bruegel the Younger altered the gaze of the walking peasant and placed him farther from the stream. Rather than glancing at the nestrobber he looks straight ahead and his foot is no longer over the edge of the bank. In Bruegel the Elder’s painting there is little prospect that the walker will right himself in time to avoid falling in the water. In the copy by Brueghel the Younger this sense of impending action is lost.

The specificity of Bruegel’s use of Brant’s text and the care he took in composing Peasant and Nestrobber suggests that the problem of an unquestioning belief in your own position had special urgency for the artist in 1568. At a time when religious animosities had caused deep divisions in the Low Countries and people were suffering from the harsh policies of the duke of Alba, including the violent persecution of any one accused of heresy, the intransigence of those who believed they were right and their opponents wrong was a deeply disturbing problem. Brant’s popular German satire, the Narrenschiff, gave Bruegel an opportunity to create a subject in which the action of each peasant corresponds to the adversarial language being used in the religious controversy. In the thirty-sixth chapter climbing too high is identified with the “Ketzer (heretic),” the fool who values his own opinion over the dogma of the church.25 Climbing too high was a familiar sign of overreaching ambition –- in the Proverbia communia it says“the best climbers oftenest break their necks”26 — but by the 1560s it was specifically associated with the Reformers and their claim that they possessed privileged knowledge about holy matters.27 In the view of their opponents the sects were climbing too high, substituting their own revelations and understanding of the Bible for the authority and accumulated wisdom of the church. The charge of heresy was made even more damning because it associated the nestrobber with iconoclastic destruction. According to the contemporary chronicler Marcus van Vaernewyck the Reform preachers urged their followers to “rob and destroy the nests where the vultures and sparrow-hawks hide, that is to say the convents that shelter them.28

For Bruegel to picture the climber robbing a bird’s nest evoked the havoc being wreaked as the iconoclasts invaded convents, churches and centers of ecclesiastical wealth, abusing clergy and nuns, burning books, breaking up organs, destroying paintings, smashing sculptures, and getting drunk on consecrated wine.29 Although the religiously motivated were often more intent on destruction than theft, in Bruegel’ s image the sack lying on the ground ready to receive the nestrobber’s booty was a reminder that others were quick to take advantage of the disorder and profit from the religious troubles.30 Writing from Antwerp about the increase in lawlessness and his fears that an insurrection is at hand Richard Clough, another contemporary observer, reported that almost every night houses were broken into and robbed, and when describing the destruction caused by the iconoclasts he assumes that the thefts were not carried out by the “Protestants” but by the “vagabonds that followed.”31 Men with large sacks slung over their shoulders run away in Bruegel’s Carrying of the Cross (1564), a realistic detail as break-ins and thefts were a constant danger when people were distracted by a public execution.32 Sacks also feature in a well-known incident in 1567 when Tournay, besieged by eleven companies of soldiers, was warned that the city would be burned to ashes and all the inhabitants put to the sword if they did not disarm and suppress the Reformed religion. When the city capitulated the disappointment of the soldiers deprived of their plunder was shared by “eight or nine hundred rascally peasants who had followed in the skirts of the regiments, each provided with a great empty bag, which they expected to fill with the booty” they would steal during the carnage.33

The adversarial language used in the religious controversy was equally relevant for the peasant about to walk in the water. Being on the wrong road was proverbial — Erasmus included “Tota eras via (you are entirely on the wrong road)” in the Adages and said that it is aimed “at those who go wildly astray”34 — but by the 1550s being on the wrong road was often identified with the “broad road” of the papists. Van Vaernewyck wrote that the Reformers condemned the clergy of the Roman church as “preachers of the broad way.”35 In a drawing by Jan Swart (ca. 1495–ca. 1563) a pope, a bishop, and others in religious garb head a procession of people four and five abreast on a broad road that descends toward hell.36 In the related drawing, people proceed up a narrow road with no sign that the Roman church has a role in their ascent toward salvation. Bruegel was familiar with idea of the broad and narrow roads and their relation to the religious struggle. Marten van Heemskerck’s print The Narrow Way to Salvation (based on Matthew 7:13–14, “Enter by the narrow gate; for the gate is wide and easy that leads to destruction) was issued by Hieronymus Cock when Bruegel was working for the publisher (fig. 6).37 In the print only those who leave the things of this world behind will be saved. Worldliness was a frequent charge made against the Roman church. Although a Catholic himself, Van Vaernewyck complained bitterly about “rich convents and abbeys enriching themselves.”38 If the peasant in Peasant and Nestrobber was seen as walking on the “broad road” of the papists it was a potent image.

Three Related Works from 1568

Being presumptuous and sure you are right is a timeless problem, but in 1568 the intransience of extremists on both sides of the religious controversy made it a life and death issue for Bruegel and his contemporaries. In Peasant and Nestrobber the text of Brant’s thirty-sixth chapter and its relation to the language used in the religious controversy gave Bruegel an opportunity to emphasize the danger, but the depth of his concern is indicated by three other paintings created in the same year — TheBlind Leading the Blind,Magpie on the Gallows, and TheMisanthrope. Each painting has a different source, but they are all dated 1568, share a similar concern with the issue of presumption, and have topical associations.

Bruegel’s Blind Leading the Blind, signed “BRUEGEL M.D.LXVlll,” is a large painting (86 x 156 cm) and one of his few works on canvas to survive (fig. 7). In this case, the issue is invoked by the text on which it is based. “If the blind lead the blind, both shall fall in the ditch” (Matthew 15:14 and Luke 6:41) is the quintessential biblical image of being misguided and losing your way. The phrase was also proverbial. In Erasmus’s Adages, “Caecus caeco dux (the blind leading the blind)” is explained as a warning against foolishly following the advice of an imprudent man. Erasmus gives the proverb in Latin and Greek adding that it is an “adage to which the Gospel text has given a wider circulation.”39

Three blind men appear as a distant detail in Bruegel’s Netherlandish Proverbs of 1559. In Cornelius Metsys’s small print Parable of the Blind Men, from ca. 1544–46 (fig. 8), there are four men. In The Blind Leading the Blind Bruegel increased the number to six. Rather than positioning their feet on the same plane as in Metsys’s print, with little sense of impending action, Bruegel placed the blind men on a precipitous diagonal so that the six successive stages in which they lose their balance create a vertiginous feeling as they fall gradually and helplessly into the deep ditch. The large space beneath the feet of the blind men, which is empty, except for a dead branch and the figures’ dark shoes silhouetted against the lighter ground, adds to the desolate feeling that the blind men have lost their way. In the copy of The Blind Leading the Blind attributed to Jan Brueghel and now in the Louvre the space in the left foreground is filled with a variety of vegetation and the effect is lost.40

Whatever one’s religious persuasion, the blindness and instability that Bruegel conveys so effectively in The Blind Leading the Blind was an accurate description of conditions in the Low Countries. The gravity of the situation was already evident in Sir Thomas Gresham’s report written from Antwerp in July 1562: “For at this instance I can write you nothing certain; but for every man speakes according to his religione.”41 By the time Bruegel painted The Blind Leading the Blind in 1568, the situation was even more complex and confusing. The sects included the Lutherans and the Zwinglians (Thomas Gresham was told that “the dissiples of Lutter and the Zwynglylans have great disputacions at Emden, for the right understanding of Holy Scripture”42) as well as Frankists (followers of Sebastian Frank), Servetiens, and Anabaptists. The Anabaptists, the most radical of the sects, had already suffered their own “schisms and divisions” with one side excommunicating the other in 1553–34.43 “Spiritualists” and “Libertines” also appear in contemporary accounts, amorphous terms that seem to have meant different things to different observers. Sir Richard Clough, the English factor, refers to “Anabaptists, Libertines, and all other kynde of damnable sects,”44 while Van Vaernewyck writes of “libertines who have the name of Calvinists.”45 In his history of the struggle Gerard Brandt mentions the “Libertines, or Free-Thinkers (which name was likewise applied to Henry Nicolas and his followers) . . . the sect which is called the House (or Family) of Love.” According to Brandt, “the Popish church swarmed” with these people who “looked upon all religions to be the same” and thought it “lawful to dissemble their thoughts in religious matters.”46

The ease with which Bruegel’s Peasant and Nestrobber evokes the language used in the religious controversies also applies to The Blind Leading the Blind. Blindness recurs again and again as a familiar charge made by each faction when castigating its opponents. Expressing the views of those opposed to Reform Van Vaernewyck writes, “Only the unhappily blind do not realize that the new dogma is the path of death.”47 Reporting on the language used by the Reformers he says the sects claim “the people are no longer blind” when inciting them to “destroy the idols of wood and stone.48

In the biblical parable, opprobrium is directed against anyone who sees the faults of others, but is blind to their own. Matthew 7:3 warns “Judge not, that ye be not judged” and Luke 6:41 asks “why do you see the speck in your brother’s eye and do not see the log in your own.” The charge of blindness could be applied to the church — the priests who kept concubines and the convents and abbeys that failed to carry out their mission of caring for lepers and the needy,49 as well as the multiple sects who put their own understanding of the Bible above the wisdom of the church fathers — but for Bruegel’s viewers the number of blind men in the painting made the sects, each with its own dogma and interpretation of the Bible, the most obvious candidates for criticism. Peasant and Nestrobber is relatively small. The Blind Leading the Blind was a large painting and likely to be displayed publicly. Caution was a necessity as the penalties for criticizing the church were severe, but as long as the blind men could be seen as representing the dissident sects the painting was unlikely to offend the authorities. Yet, the blind men invite a more tolerant response. The care that Bruegel devoted to their faces emphasizes their humanity and invites pity as they grope their way forward with faces uplifted toward a light they cannot see.

In Magpie on the Gallows from 1568 the dangers of presumption are again central to Bruegel’s conception (fig. 9). Signed “BRVEGEL 1568,” it is a relatively small painting (45.9 x 50.8 cm) that seems to have remained with Bruegel’s wife after the artist’s death the following year. According to van Mander, Bruegel willed “Magpie on the Gallows” to his wife and “by the magpies he meant the gossips he wished to send to the gallows.”50 While accepting van Mander’s title most scholars have found his explanation unsatisfactory. It leaves too many questions unanswered. Unlike Peasant and Nestrobber and The Blind Leading the Blind there is no source, literary or visual, to guide the interpretation yet the subject raises the same problem — believing you are on right when you are heading for disaster. Instead of ending in the water or falling from a tree the peasants are dancing toward the gallows, the ominous dark shape that creates a disturbing contrast to the beauty of the landscape in the distance.

By 1568 dozens of people were being hung from the gallows or burned at the stake. Anyone who attended a “green church” (or “hedge preaching”), engaged in an act of iconoclasm, composed a satire, or sang a psalm publicly was open to attack and could be condemned as a heretic.51 A familiar sight in the Low Countries, the gallows appears in a number of Bruegel’s prints and paintings. Bodies hang from the gallows in Justicia (Justice) from his series of the Seven Virtues, a gallows stands near the execution field in the Carrying of the Cross, his earlier painting about the persecution of Christians, and a man squats near the foot of a gallows in Netherlandish Proverbs where the image illustrates the proverb“To shit on the gallows” (to express contempt).52 In Magpie on the Gallows the squatting peasant is half-hidden in the corner of the painting, but the gallows retains its threatening role as an instrument of death.

Light coming from the left dramatizes the gallows, the rock on which it stands, the tree stump, a dead branch, and the two magpies. The impracticality of the rock as a support for the gallows suggests it has a symbolic role, perhaps as “the rock of scandal . . . upon which are broken all who . . . impede the word of God with their own traditions (I Peter 2:7)” or as “the rock” of the church (Matthew 16:18), the authority responsible for sending people to the gallows.53 The dead stump next to the rock is in a position similar to that of the jagged stump in the center of Bruegel’s Rabbit Hunt, an etching from 1560 that illustrates the cautionary proverb “A hare yourself you hunt for prey.”54 In the etching the rabbit hunter is so intent on his prey he fails to notice the stealthy approach of a man carrying a long and ominous weapon.55 At a time when informers could betray people to the authorities and be rewarded with half their estate if their victims were convicted of heresy the proverb was a timely reminder that people could “hunt” their neighbors and there was reason to be cautious.56 The decayed stump in Magpie on the Gallows has similar connotations; the dead branch next to it is a grim detail that contrasts with the greenery visible in the rest of the painting.

The magpies complete this ensemble, their position on the stump and the gallows suggesting their reputation as an evil bird, carrier of tales and a troublemaker, and another reminder of the danger of informers. Erasmus casts the crow in this gossipy, malevolent role in the 1553 edition of the adages where “Cornicari” appears in the section headed “Garrulitas.” He says the proverb is taken from Persius (Satire V) and refers to someone who “croaks . . . solemn nonsense with hoarse mutterings like a crow.”57 In Barthélemy Aneau’s Imagination poetique, published in 1552, blackbirds represent clandestine enemies (“corbeaux crians & pies caquetantes”) that cause the death of virtuous men.58 The combination of gallows, rock, blackbirds, and stump underscores the danger the merry-making peasants are ignoring as they dance toward the gallows, their topical associations suggesting that in this more private work Bruegel felt free to criticize the church’s response to the heretics, a policy that had little to do with true Christianity as the Erasmians understood it or with the tolerance advocated in Bruegel’s grisaille Jesus and the Woman Taken in Adultery of 1565.59

The Misanthrope, the third work related to Peasant and Nestrobber, is a large painting (86 x 85 cm), signed “BRUEGEL 1568,”60 and is another of his works on canvas (fig. 10). The circular scene within a deep lavender surround is dominated by the solitary figure of a man with a long white beard walking with hands folded and head bowed through a broad and desolate plain, a windmill and a shepherd tending his sheep in the distance. His face is partly hidden by a voluminous dark blue hooded cloak, but the sour expression of his down-turned mouth is clearly visible. The lines in dialect below his feet are probably a later addition, but their gloomy view –“Because the world is perfidious, I go in mourning” — is a fitting accompaniment to the embittered old man. The old man’s path is blocked by three sharp objects. Behind him a symbolic figure reminiscent of the fantastic image of the world in Bruegel’s Netherlandish Proverbs, is stealing his purse, its heart-shaped form and dark red color suggesting that money is the true object of the old man’s affection. Like the blind men in The Blind Leading the Blind and the peasants in Peasant and Nestrobber and Magpie on the Gallows the old man believes he is on the right road when he is about to lose his money and step on sharp objects.

Bruegel’s unusual subject was probably suggested by someone familiar with Timon, the misanthrope, the disillusioned man who rejects the world, as he is described by Cicero and other ancient authors published in the Low Counties in the 1560s.61 Timon appears as an “inhuman soul” in Johannes Sambucus’s Emblemata (published by Christopher Plantin in Latin in 1564, Netherlandish in 1566 and French in 1567).62 Victor Giselinus’s Adagiorum (published by Plantin in 1566) includes two proverbs about Timon, including “A Timonian Meal” — an attack on those who hide their wealth and pretend poverty63 –an apt proverb for the old man with his money bag hidden under his dark blue cloak, the color of his garment a revealing detail as blue was associated with deceit.64

The sharp objects that lie in the misanthrope’s path suggest the “thorns” that serve as punishment in Brant’s Narrenschiff. In the thirty-sixth chapter it says that if you miss the road and go astray you will be “scratched with sharp thorns (Der Kratzt sich mit den Dornen schar).”65 The objects that block the misanthrope’s way have the same role as the thorns in Brant’s text, although their metallic look makes them appear even more dangerous, their sharp points identifying them as caltrops, a cruel military device for impaling the enemy. The weapon was being manufactured locally — Van Vaernewyck says that caltrops were being forged at Malines in 156866 — and as one of the weapons being used in the warfare that engulfed the Low Countries it was a timely substitution for Brant’s thorns.

By the time Bruegel painted The Misanthrope in 1568, the duke of Alba had arrived from Spain with full power to punish all abuses of religion. As a result of his stringent policies, among them arbitrary imprisonments, confiscation of goods, torture, and executions, the Low Countries were in a state of civil war and people were leaving by the hundreds, an extraordinary exodus witnessed by Richard Clough.67 Writing from Antwerp in March 1567 Clough reports on the large number of wealthy people “preparing to fly the country” and he marvels, “to see how the pepell packed away from hens . . . the papists as the protestants: for it is thought that howsomever it goeth, it cannot go well here; for that presently all the wealthy and rich men on both sides, who shuld be the stey of matters, make themselves away.”68

When the prince of Orange left Antwerp in April Clough reported there were “4 or 500 rich men ready to ride away with him,” the panic fueled by the final departure of the prince causing an even larger number to flee, so many that the duchess of Parma wrote King Philip that upward of a hundred thousand had left the provinces.69 The situation was so alarming that a governmental pronouncement of September 1567 made it a crime to leave the country, with punishment mandated even for those who knew of an impending departure and failed to report it.70 This out-migration, which was destroying the economy of the Low Countries, proved a gain for other countries as the émigrés brought their money and their skills with them. A census taken in the same year by order of the bishop of London shows that of almost 5,000 strangers in the city, 3,838 were from the Low Countries.71

The misanthrope walking away and taking his moneybag with him was an apt metaphor for those departing the Low Countries in order to save themselves and their possessions — his philosophical pose a sham adopted to conceal his true motives. A different response to the dire situation is suggested by the shepherd in the distance, who leans on his staff, remaining at his post while others leave. In Bruegel’s Parable of the Good Shepherd of 1565, the bad shepherd runs away while the good shepherd protects his sheep and fends off the wolves.72 Like blindness, the metaphor of the shepherd was used by all sides in the religious controversies. Van Vaernewyck writes of a priest who continued to preach at the risk of his life, but he also reports that those leaving the country included priests who “deserted their parishes and abandoned their flocks leaving them in the power of the wolves.”73 From the perspective of those who stayed the misanthrope’s decision to leave could be seen as a self-serving strategy, the loss of his moneybag and the sharp objects in his path a fitting retribution for having missed the right road.

Bruegel as Witness

As a guide to Bruegel’s views on the troubles of his time, Peasant and Nestrobber has the advantage of being entirely by his hand. Assistants may have ground the paints and prepared the ground but the brushwork is clearly Bruegel’s own. Innovative paintings such as his Children’s Games of 1560 were also done without assistance, but the investment in time and materials given their large size, complexity, and unfamiliar subjects required an involved patron to initiate the project and support it financially.74 Bruegel’s Peasant and Nestrobber is smaller and could be purchased by someone simply eager to own a peasant painting, with the artist free to choose the situation in which they were presented. The Blind Leading the Blind was a familiar biblical subject making a participatory patron and detailed instructions equally redundant. Workshop participation was more apt to be required for a large painting filled with dozens of figures, such as the recently discovered Feast of Saint Martin (148 x 270 cm).75 The Misanthrope (86 x 85 cm) required someone knowledgeable about ancient literature, but its relative simplicity meant there was little need for assistance or extended consultation with the buyer. An engaged patron and workshop participation are even less likely for Magpie on the Gallows as it seems to have remained in the family after Bruegel’s death in 1569 and probably had a personal meaning for the artist. Whether the Peasant and Nestrobber was painted first is a question that cannot be answered since all four paintings are dated 1568. Perhaps Bruegel simply recognized in Brant’s text another opportunity to address an issue that was already engaging his attention. Whatever the case, all four paintings deal with the same problem — being presumptuous and sure you are right. Their shared concern suggests the subjects were chosen on Bruegel’s own initiative, or if a patron was involved, someone willing to give him a free hand.

In 1568, Bruegel was a married man with young children, living and working in Brussels at a time when the city was beset by all the usual problems of urban life, including fires, food shortages, and epidemics — during the hard winter of 1567 a fire broke out in Brussels in January, destroying some twenty to twenty-four houses,76 and in the fall of 1568 there was a return of pestilence.77 Bruegel may not have witnessed Alba’s entry into Brussels in August 1567,78 but as he lived in the city he would have witnessed the effects of this invasion — the dislocations in daily life, the food shortages, disruption in trade, requisitioning of houses, confiscation of household goods, people arrested in their beds, arbitrary imprisonments, reports of torture, and the spectacle of gruesome public executions that spared neither rich or poor, young or old. The nobility were usually decapitated — the fate of Counts Egmont and Horne, who were killed in June 1567 in the public square in front of the Brussels town hall and had their heads stuck on pikes79 — while others were hung or burned.80 If Bruegel witnessed the five cartloads of prisoners that were brought from Antwerp to Brussels in 1568 and paraded through the streets before the victims were tortured and killed, he would have recognized some of these men as he had worked in Antwerp for many years.81

Bruegel could not avoid being affected by these devastating events, but since his survival depended on being circumspect, it is often difficult to judge who is being criticized in his art or even whether criticism is intended. His masterful small drawing of three soldiers is dated 1568 and while it alludes to the military presence he shows the pageantry and not the havoc the armies were creating.82 That more dangerous kind of reporting was left to someone like Frans Hogenberg, an artist in a less vulnerable position as he was living in Cologne, many of whose prints are based on reports of the conflagration rather than direct observation.83 Yet, the topical associations available for robbing a bird’s nest or failing to find the right road suggest that in Peasant and Nestrobber Bruegel was expressing his personal opposition to extremists on all sides, all those who were convinced of their own position and intolerant of others. Years later when his son painted his version of Peasant and Nestrobber conditions had changed and his father’s painting could be valued simply for its landscape and depiction of peasant culture. In 1568 the situation was very different. The elder Bruegel’s use of Brant’s Narrenschiff and the care he took in constructing Peasant and Nestrobber testifies to the ingenuity of an engaged artist trying under difficult condition to express his own views about the dangerous time in which he lived.

Recognizing the thirty-sixth chapter of the Narrenschiff as Bruegel’s source for Peasant and Nestrobber and its relation to the language used in the religious controversy, also makes Bruegel’s drawing of the beekeepers more intelligible (fig. 3). The beehive appears as a symbol of the papacy in Bruegel’s earlier works. In his drawing for the 1559 series of the Seven Virtues, three fishing poles strategically placed behind the beehive headdress of the allegorical figure of Spes (Hope) make a subtle allusion to the papacy. A beehive is also worn by the representative of the church in his painting Battle Between Carnival and Lent from the same year.Given Bruegel’s earlier usage and the 1569 publication De Bienkorf der Roomsche Kercke (The Beehive of the Holy Roman Church) by Marnix van St. Aldegone,it is likely that the beehive has same role in The Beekeepers.84 Jetske Sybesma claimed that the beekeepers represented, “those who restore order to the Catholic parish churches,”85 yet their behavior suggests otherwise. One hive has fallen over and another is unattended. By the late 1560s the Reform preacher’s directive to “rob and destroy the nests” was being carried out through the continued destruction of churches, convents, and other religious establishments.86 Many of those responsible for maintaining the church and defending it from attack were failing in their duty. Priest and monks were among those leaving the church and joining the Reform sects, defections that could be associated with the beekeeper in the center of the drawing walking away empty-handed.87 Other clergy remained in the church but chose to hide or emigrate to safer territory rather than stay and tend their flocks — their flight suggested by the beekeeper slouching off and taking the “church” with him.88 A third option, to turn the beehive upside-down in the hunt for heretics, could be identified with the beekeeper prying the beehive open, a counter-productive and violent response to heresy that alienated even those who remained within the church. While the beekeepers are busy pursuing their own agenda the man in the tree is free to continue his activities. Compared to the precarious perch of the nestrobber in Peasant and Nest, his position is more secure, and since he is facing the unattended beehive it suggests the iconoclasm will continue unabated.

For those witnessing the dissolution of the society in which they lived, the negligence of the beekeepers could be just as troubling as the multiple sects with their destructive activities, but whatever observations Bruegel was making about the religious situation, the ambiguity with which they are presented insured that the artist would avoid being troubled by the authorities. Abraham Ortelius, Christopher Plantin, and Hieronymus Cock, men who can be associated with Bruegel, remained in the Low Countries throughout this terrible period and in spite of the troubles they continued to work, write, and publish. Peasant and Nestrobber suggests that Bruegel saw presumption and arrogance on all sides — the intolerance of the church as well as the dogmatism and destruction of the Reform, a position close to that of the reform-minded Erasmians, followers of the “middle way,” who were more concerned with leading a Christian life than following the dogma of any organized church.

After quoting Virgil’s Georgics in his letters Saint Jerome advised that if one wishes to lead a Christian life and stay out of trouble, “keep busy, raise bees.”89 Perhaps this was Bruegel’s response to the upheaval around him: to bear witness and keep busy making art. In the fourth Georgics, Virgil says that raising bees “is labor bestowed on a trifling subject, but not trifling in its glory (in tenui labor et tenuis non gloria).”90 Above all, Peasant and Nestrobber demonstrates that in the hands of a gifted artist a scene of ordinary life could be both timely and timeless.

Conclusions

Bruegel’s Peasant and Nestrobber is about the dangers of being presumptuous, sure you are in the right when you are headed for disaster, a subject with topical interest in the Low Countries in 1568. His source for the painting, the text of the thirty-sixth chapter of Sebastian Brant’s popular Narrenschiff, accounts for both peasants — the man about to fall in the water and the man robbing the bird’s nest. Brant’s text also establishes their significance as warnings about the danger of being headstrong and sure of your own position. The importance of this problem for Bruegel is evident from the thematic and visual connections Peasant and Nestrobber shares with three other paintings — The Blind Leading the Blind, Magpie on the Gallows, and TheMisanthrope. They were all painted in the same year and while they have different sources — a German satire, a biblical text, and classical literature — they all address the same problem. The peasant in Peasant and Nestrobber believes he is on the right path when he is heading for the water. The nestrobber is sure he won’t fall. The blind men do not realize they are headed for the ditch, the misanthrope fails to see the sharp objects in front of him, and in Magpie on the Gallows the peasants dance blithely toward the gallows.

Being headstrong and convinced you are right is a timeless problem, but in 1568 it characterized the intransigence of extremists on all sides of the religious controversy, the escalating conflict that was creating such havoc and hardship in the Low Countries. In earlier works, Bruegel had innovated by treating ordinary scenes of daily life as suitable subjects for a serious artist. In Peasant and Nestrobber the ordinary becomes a vehicle for criticism, with the behavior of each peasant having its counterpart in the language being used in the religious conflict. In a time of polarized positions and governmental repression these topical associations provided Bruegel with an ingenious way of expressing his own views of the conflict without fear of retaliation. This ambiguity also serves to enrich the viewing experience. When a painting resists easy comprehension it invites participation, involving the viewer and maintaining interest. A work by Bruegel is never about one thing only. His art is too complex. Yet, his efforts to bear witness to what could not be expressed openly may be one reason his art invites such close attention, raises so many questions, and has so often prompted the attentive viewer to consider larger questions about humankind, our relation to each other, and to the world in which we live.