Rembrandt and Breenbergh began their Amsterdam careers in the early 1630s, introducing styles that were a great novelty in Amsterdam. This essay argues that these two highly talented and ambitious young artists responded to each other’s works when painting their versions of The Preaching of John the Baptist. First Breenbergh reacted to Rembrandt’s grisaille when he painted the panel of 1634 now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (acquired by Walter Liedtke); subsequently Rembrandt responded to Breenbergh when he enlarged his composition, and finally Breenbergh responded in turn when painting a second version of this subject. Their goal was to demonstrate to an audience of discerning connoisseurs their contrasting views about what makes a good small-figured composition of a history subject. How serious Breenbergh was in “correcting” Rembrandt’s “from life” ideology, applying the traditional rules of decorum in an up-to-date Roman idiom, is even more pronounced in two paintings of Christ and the Woman of Samaria; both are an immediate response to Rembrandt’s etching of the same subject dated 1634.

When looking through Bartholomeus Breenbergh’s oeuvre, it is unlikely that Rembrandt’s name will come to mind. However, different as their works may be, it is plausible that the two artists were interested in each other’s achievements: two highly talented and ambitious painters, who, from the early 1630s onwards, were both making their careers in Amsterdam. They both favored biblical subjects for their histories, and were both greatly interested in Pieter Lastman’s compositions. The styles of both Rembrandt’s and Breenbergh’s paintings were a great novelty in Amsterdam and their reputation must have been considerable. In an amazingly short time Rembrandt had become fashionable among the Amsterdam elite; having sold several paintings to the court and working on an important commission for the stadholder would have enhanced his prestige. Breenbergh’s renown is evident from the fact that King Charles I of England granted him an annuity in 1633, while his paintings were bought by Italian, French, and English collectors from early on. Possessing an intimate knowledge of the monuments in Rome as well as of the latest achievements of artists in that city would also have been an important asset in Amsterdam, where no other artists could boast this background at that time.1 One would expect that, in this small community, these two artists would each have kept a sharp eye on what the other was doing. And indeed, a few works testify that during a short time in the mid 1630s they responded to each other’s works. I will argue that one might even speak of a dialogue about what makes a good small-figured representation of a scene from history, demonstrating their contrasting views for an audience of connoisseurs.

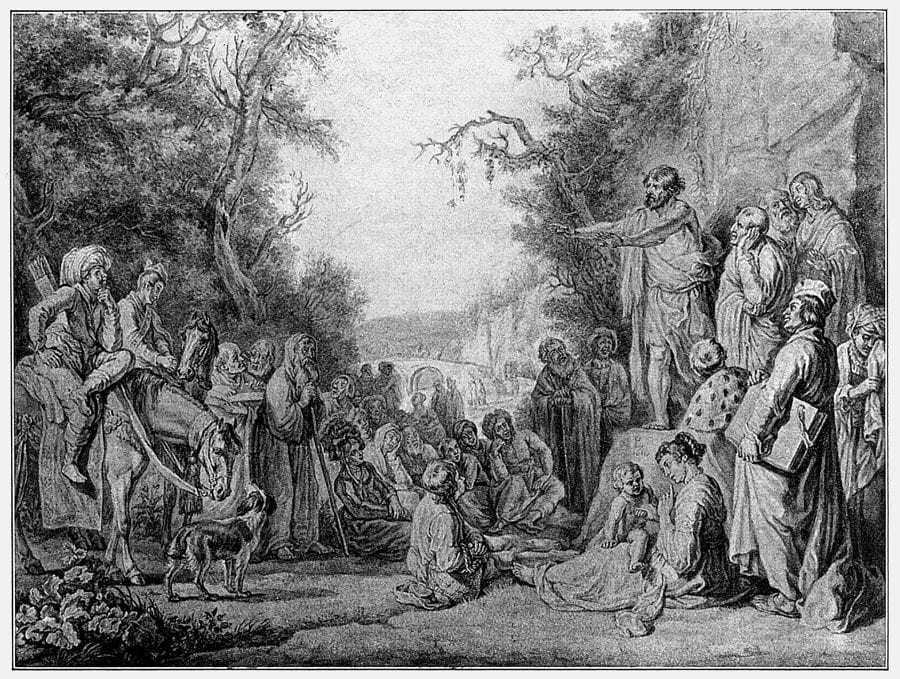

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s magnificent Preaching of John the Baptist, dated 1634, which was purchased by the museum under Walter Liedtke’s curatorship in 1991, is the centerpiece of this dialogue (fig. 1). A few art historians have noted the fact that Breenbergh and Rembrandt painted the same subject almost simultaneously (fig. 2).2 Apart from Walter Liedtke none of them pointed to similarities in the composition or suggested a relation. Walter, however, when he announced the acquisition of the painting in a brief notice in the MMA Bulletin, wrote: “Rembrandt . . . found inspiration in this [Breenbergh’s] picture for his grisaille painting of the same subject, now in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin.”3 Remarkably, he does not return to this notion in his beautiful five-page entry on the painting in his catalogue of the museum’s Dutch paintings of 2007.4 There he only mentions Rembrandt’s work when enumerating a few Dutch artists who also depicted this subject. I will follow up on his original suggestion and demonstrate that his first reaction to Breenbergh’s composition was—partly—right.

Walter Liedtke, who loved this painting and was very proud of its acquisition, rightly suggested that Breenbergh’s panel was meant as “a special demonstration of his abilities” and that he “after a decade’s residence in Rome . . . intended, by producing masterworks like this one, to make a name for himself in his native country,” pointing out, among other things, “the remarkably diversified survey of curious types in the crowd around John the Baptist.” An exceptional diversity was also remarked upon in relation to Rembrandt’s grisaille; we read for example in A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings: “the picture is unique among Rembrandt’s work for the variety of exotic figures, with specific facial types and attributes.”5 In the case of both artists this has always been considered their main characteristic. Samuel van Hoogstraten, when describing Rembrandt’s work, emphasized the “amazing attention of the audience consisting of people of multifarious ranks and degrees; this was highly laudable.”6 Breenbergh’s painting was praised by the famous eighteenth-century collector Johan van der Marck with the words: “so beautiful in its drawing and depiction of the passions, variety of costume and elaborateness of painting.”7 These were the terms in which the admiration for both works was couched in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

It must have been a conscious goal of both masters to render a stunning varietas and copia, and one may ask if they were trying to outdo each other in this respect. Since Pieter Brueghel’s Preaching of John the Baptist, known through many copies and variations (the primary version, dated 1566, is in the Szépmûvészeti Múzeum, Budapest), this was pre-eminently a subject that lent itself to the display of a great variety of people in all kinds of exotic dress. Abraham Bloemaert, Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem, and Joachim Wtewael had painted the subject as demonstrations of virtuosity in the differentiation of people’s age, gender, appearance, dress, attitude, and emotional reaction. Rembrandt and Breenbergh would push this to the extreme. I counted sixty-seven figures in Breenbergh’s painting and about sixty-eight are recognizable in Rembrandt’s work—that is, in the final version, after he had enlarged it. The first version of Rembrandt’s grisaille, much smaller than the present painting and meant as a model for an etching, would have contained approximately forty figures (fig. 3).8

Breenbergh and Rembrandt knew well a composition by Pieter Lastman (lost, but known through an eighteenth-century drawn copy; fig. 4), because they both took it as point of departure for their own works. It is as if they wanted to honor the older artist (who had died the year before) by “diligently pursuing the old art with a new argument, thus adroitly bestowing their painting with the pleasurable enjoyment of dissimilar similarity,” to quote Franciscus Junius when he talks about emulative imitation.9 I assume that the first version of Rembrandt’s spectacular grisaille, in all probability also dating from 1634,10 stimulated Breenbergh to show off his conception of how to paint a large crowd of highly varied figures in a landscape.

In the disposition of the group of figures around Saint John, Breenbergh kept close to Lastman’s composition: we recognize a group of men standing behind and below the saint, a woman with a child in the foreground, a group of seated people in front of Saint John, and to the left of this and closer to the viewer a group standing, while listening attentively (Breenbergh placed the turbaned horseman in the background of this group). In Luke 3:12–14, the only specifically named people whom Saint John addresses are soldiers and a publican, which must have been the reason that Breenbergh depicts those as the most conspicuous figures among the audience. The publican stands in the middle, with a huge purse hanging on his belt; Breenbergh has transformed the old man leaning on a stick in the middle of Lastman’s composition, a motif we also find in mirror image in the middle of Rembrandt’s work. Most striking are the military men: with apparent pleasure Breenbergh depicted two Landsknechte, with their flamboyantly feathered hats and showy, colorful costumes full of slits, costumes that were considered to be of ancient origin and therefore fitting within the decorum of this scene.11 The one at the left of the group in the middle is based on a print after Hans Schäufelein, the one at the right taken from a print by Jacques Callot.12 Two Roman soldiers are standing at the extreme right, while a handsome Roman warrior, also dressed in carefully observed antique armor, is sitting before Saint John and intently listening, supporting his chin with his hand; this figure is a variation on a similarly positioned man in Lastman’s work. Equally conspicuous is the Turk wearing the same type of turban (high in the front) as Rembrandt’s man on horseback, but Breenbergh seems to refer more specifically to the man standing under the cross in van Vliet’s Descent from the Cross etched after the Rembrandt painting of 1633. Another striking figure is the young standing woman looking up at Saint John, richly clad in silk and with pearls in her hair and ears; she is not present in Lastman’s or Rembrandt’s composition, but the choice to add her among the main group may have been incited by Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem’s painting of the same subject, dated 1602, which might have come on the art market in Amsterdam in the spring of 1634 (appraised at the substantial sum of 100 guilders) (fig. 5).13

Behind the main group we find many figures with headgear in all kinds of exotic shapes, which, apart from the turbans, we do not find in earlier works by Breenbergh. Rembrandt’s great variety of hats—flat disklike headdresses, high hats in different shapes, different types of berets, all kinds of turbans, even three feathered Indian headdresses (two with small feathers, a third with long feathers)— must have triggered Breenbergh to do something similar. He kept closer to the tradition; the Landsknecht was already familiar in this company since Brueghel’s Preaching of John the Baptist and returns in all the paintings by Bloemaert and Cornelis Cornelisz of this subject. The same is true for the woman with the flat circular hat. Other strange hats very much recall the ones seen in The Preaching of John the Baptist by Cornelis Cornelisz mentioned above; there we also find quite a few examples of weird headgear. Rembrandt seems to have known this painting, too. To the old man leaning on his stick Rembrandt added two men hotly discussing Saint John’s words, probably representing the Pharisees and Sadducees addressed by the saint as “vipers” (Matthew 3:7); they recall the two talking men standing at the left of the middle group in Cornelis’s painting. The white rectangle on the forehead of the gesturing man in Cornelis’s painting might also have contained a text in Hebrew lettering, as we know it from another work by Cornelis.14 Rembrandt turned this into a real prayer band with a text in Hebrew lettering.15 Also the idea to have to the left of these men a group of people in leisurely attitudes—one has brought a basket with food, turning the occasion into a picnic—seems to have originated in Cornelis’s work.

It is hard to say what Rembrandt’s original small version looked like, because on this part of the canvas, several figures might have been added in the second stage, when it was enlarged (see figs. 2 and 3). However, the turbaned man on horseback at the left was there from the start, as were some of the sitting figures in the highlighted area in the middle (among them a mother hushing a screaming child), the old woman with a book, and the men to the right standing at a lower level. In the X-radiograph a figure seen from the back and partly covering Saint John’s lower right leg, in the same position as in Lastman’s composition, can also be seen; he has disappeared in the second stage. The bridge with two arches in the background of Lastman’s composition reappears in Rembrandt’s work but was painted after the enlargement. Originally there might have been such an arched bridge on a much smaller scale, directly behind the man on horseback.16 In this first version of the composition Rembrandt remained close to Lastman’s format in the framing of the composition and the scale of the figures.

At some point, however, Rembrandt must have seen what Breenbergh had done with the subject—probably in response to his own painting—and have decided to enlarge his grisaille on all sides so that the scale of the figures became more or less similar to those of Breenbergh. Like Breenbergh, he added the deep dark valley to the left and emphasized the mound on which the main group is placed in relation to this lower middle distance. In the direct foreground he also depicted a dark strip as a repoussoir along the whole width of the painting, and he raised the mountainous landscape background (originally the sky probably extended to the level of the heads of the men on horseback).17

In Breenbergh’s method of constructing three-dimensional space, the mound on which the main group is situated functions as a clearly defined stage on which the figures are carefully placed, each of them precisely delineated, rounded and detailed, and thus occupying its own space in a distinct relation to the position of other figures. The shadowed slope at the left, beginning on a lower level and rising to a ridge, is crowned by Roman ruins; a highly refined backlighting shines through an opening to define the ruins and create space for a number of tiny figures. This darker second plane, as well as the bluish green background, sets off the mound with the main group. In Rembrandt’s grisaille, a strong sense of space is created in an entirely different way. The spatial organization is attained by strong lighting in the middle and by dark areas that function as schikschaduwen (shadows to arrange); this gives a solid coherence to the whole composition as imagined in three dimensions.18 Through subtle modulations of light and dark, especially within the circle of light before Saint John, all the figures receive their proper place in space. Thus, he diverged radically from the traditional construction of a “stage” peopled with clearly outlined figures, as was recommended in all sixteenth- and seventeenth-century art literature. Rembrandt’s method of “deliberate manipulation of light and shadows . . . to beautifully highlight one thing by obscuring the other” was, however, not something everyone was happy with, as Samuel van Hoogstraten would later make clear.19

When devising the larger version, which he did, as suggested above, in response to Breenbergh’s work, Rembrandt would have been prompted by Breenbergh’s even larger number of people and greater variety of types and costumes to add numerous exotic figures, among them a man clad in Japanese armor at the left and a Turkish warrior, an East Asian, and several turbaned Arabs at the right. He also added, as in Breenbergh’s painting, a woman with a child in the right foreground below Saint John. In the dark shadow to the right he painted a fishing boy, a woman holding a child that relieves itself, and in the shadow at the lower left two fighting dogs and two copulating dogs. Much later Samuel van Hoogstraten still remembered the latter, giving this as an example of an unforgivable breach of decorum: “yet one saw also a dog that in a most scandalous manner was mounting a bitch. One might well say that this is something that can happen and is natural; but I say that it is an abhorrent indecency in the context of this story . . . such scenes betray the artist’s lack of judgment.”20 From this sentence it is evident that some people must, indeed, have been saying “that this is something that can happen and is natural” (it is not unlikely that he heard such words from the master himself), but that for others this was unacceptable. Breenbergh demonstrated how to stay entirely within the rules of decorum: the figures are as differentiated as possible and neatly characterized in age, gender, type, and degree of attention, but no one is ugly and no one stands or sits in an ungainly pose. They all possess a certain conventional gracefulness in attitudes and gestures. In contrast, Rembrandt depicted none of his figures with conventional poses or gestures, and he deliberately did away with any sign of gracefulness. The attitudes of his figures are emphatically studied from life and express all kinds of emotions, which he underlined by such motifs as the angry man growling at two fighting brats (below Saint John), in what was originally the right foreground. It seems to be no coincidence that for no other painting by Rembrandt do so many directly related figure sketches exist and that it was this work which made Houbraken remark that pupils told him Rembrandt could endlessly sketch facial features to catch them as naturally as possible.21 Grace, a central tenet of traditional art theory, had been radically jettisoned.

Breenbergh had responded to Rembrandt by depicting just that: grace and decorum as he had learned it in Rome, executed with a careful design. When enlarging his composition Rembrandt reacted in kind by laying it on more thickly. He transformed, for example, Breenbergh’s Domenichino-like woman with her handsome, elegant child, which we find in a similar position as onlookers in works of Reni and Domenichino,22 into a mother sitting with her legs wide apart, one leg ungainly stretched, to give room to a grinning gnomelike child, which she crowns with a wreath of flowers. Moreover, he threw in another highly inelegant mother holding a defecating child and, to make it worse, the two copulating dogs—thus defiantly making the scene even more “natural” than it already was.

A few years later Breenbergh responded to Rembrandt’s final version. In 1643 the former made a much larger painting, a masterpiece in which he reduced the number of figures drastically (fig. 6). When scrutinizing the painting carefully the viewer still finds about twenty-five figures unobtrusively placed elsewhere in the landscape (among them Breenbergh included figures above Saint John looking down on him from the tree, as Rembrandt had done), but now Breenbergh focused on a few large figures standing and sitting around the saint. He depicted a serene southern landscape bathed in low evening light, in which we recognize several figures that still refer to Lastman but also to Rembrandt and to his own earlier painting, now all transformed into a quiet monumentality. A broad-shouldered variant of Lastman’s long-robed figure with a large book under his arm standing at the right now addresses an arguing Pharisee with a text-band on his forehead. The latter is based on Rembrandt’s figure in the foreground, but the tense frantically arguing attitude of that man is turned into an erect pose of authoritarian admonishment. Lastman’s mother sitting in the foreground with a raised finger hushing a crying child, who had been changed by Rembrandt into a mother urgently bending over a screaming toddler, has become a calm and decorous “correction” of both this mother and the one with the ungracefully extended leg that Rembrandt had placed in the foreground. The intently listening turbaned man and richly clad woman from his earlier version return in this painting as central figures, to which an attentive mother suckling a child has been added—in Rembrandt’s painting we discern her in the group to the left of the standing Pharisees—sitting on the ground and seen in profile. The Roman soldier supporting his chin with his right hand from Breenbergh’s earlier work has been turned ninety degrees and become a contemporary traveler seated in the foreground, functioning as an identification figure for the viewer. To underline his Roman background, Breenbergh placed a muscular nude male in the foreground that looks like a Carraccesque academic study striking the pose of an antique river god.23

Evidence of how serious Breenbergh was in “correcting” Rembrandt’s “from life” ideology, in accordance with the traditional rules of decorum applied with an up-to-date Roman idiom,24 is even more pronounced in two paintings of Christ and the Woman of Samaria; one, like the Metropolitan Saint John, dates from 1634 (fig. 7) and the other probably from around 1635 (fig. 8). Both are an immediate response to Rembrandt’s etching of 1634 (fig. 9), and they are simultaneously Breenbergh’s first works with figures on a larger scale. They seem like a lesson in bevallijckheyt—grace according to academic norms. The placement of the figures in the composition and their poses have many similarities with those of Rembrandt, but Breenbergh filtered them through his Roman education. Especially in his second work he turned Rembrandt’s emphatically true-to-life figures into an equally radical classicism. The figures in the first version—a tiny painting of exactly the same height as Rembrandt’s small etching!—are a more stylized version of Rembrandt’s. In the second, however, he turned Christ parallel to the picture plane and transformed him into a highly idealized Carracci-type; the broad, slightly angular drapery also evokes Annibale Carracci.25 The beautiful Samaritan woman, placed in strict profile, recalls Domenichino’s Timoclea before Alexander (Paris, Musée du Louvre) but with the face of an early Poussin Madonna.26 Breenbergh must have made careful studies of such figures and used them here as if to instruct his Dutch audience in the mid-1630s in Bolognese-Roman disegno, explicitly contrasting them with Rembrandt’s manner. He could not have chosen a better way to display the “cultural capital” that he had earned in Rome, thus defining his distinguished place within the Amsterdam art scene.