Nikolaus Glockendon (ca. 1490/95-1533/34), the foremost illuminator of sixteenth-century Germany, made a career of copying the compositions of other artists, especially those of his Nuremberg contemporary Albrecht Dürer. Like Dürer, Glockendon was the acknowledged German master in his field, supported by elite patronage and impressively high fees, with a productivity attested to by a large body of identified works. This paper contextualizes Glockendon’s imitative practice within the traditions of medieval art, the hierarchy of style in late medieval literature, the practice of finishing in illuminated manuscripts, the entrepreneurial trends in book illustration after the invention of printing, the contemporary conceptions of artistic property and conventions of exchange, and the documented standards of value in sixteenth-century German craftsmanship.

The Cardinal’s “Musician”

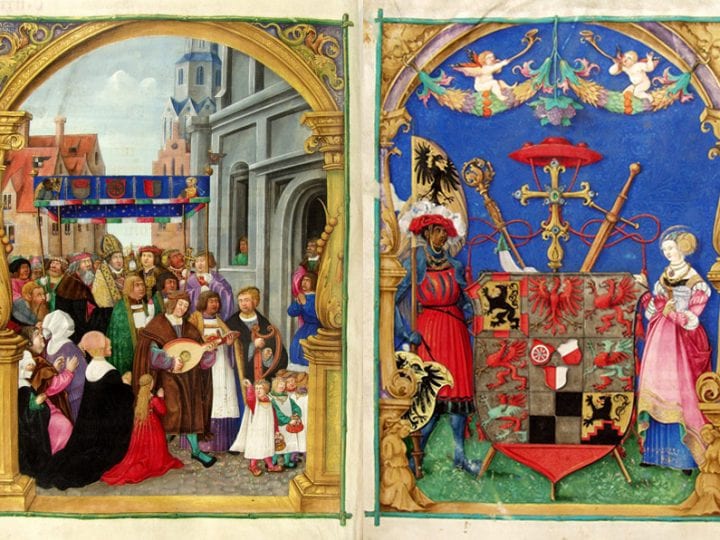

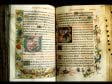

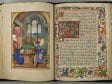

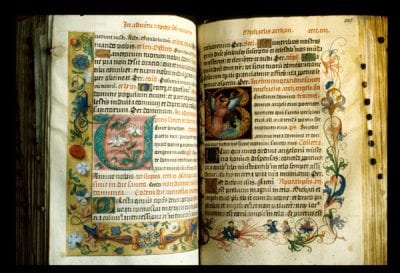

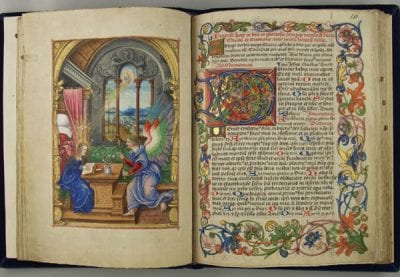

Among the masterpieces of German Renaissance art is an illuminated manuscript in the Hofbibliothek at Aschaffenburg. Preserved in its original sixteenth-century binding, embellished with engraved vermeil plaquettes and gold and silver page-markers, Ms.10 is an intentionally magnificent ceremonial missal decorated with sumptuously painted borders, an illustrated calendar, ninety-three historiated initials, and twenty-three full-page miniatures (fig.1).1

Made for Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg (1490-1545), the Missale Hallense (a missal for the cardinal’s church at Halle) not only attests to the extravagant tastes of its patron but also demonstrates the masterful skill of its maker, Nikolaus Glockendon of Nuremberg (ca.1490/95-1533/34).2 The foremost German illuminator of his generation, Glockendon belonged to a family of Nuremberg artists who for at least three generations worked in illuminated manuscripts, painted coats of arms, prints, publishing, and cartography.3 Nikolaus Glockendon signed and dated the Missale Hallense in 1524 and, it has been suggested, may have included an image of himself in one of the full-page miniatures, that of the Corpus Christi Procession (fig. 2).4 In this documentary-style depiction of the celebrations for a sacred feast day, a figure of a finely dressed court musician, plucking the strings of a small harp, gazes directly at the viewer, as if to invite us to join the throng of worshipers as they approach the entrance of the church. The engaging harpist and his companions herald the arrival of the procession as well as announce the ultimate purpose of the manuscript: the unabashed celebration of the patron, who marches as presiding bishop and carries a gold monstrance underneath a liturgical canopy. Although the identity of the harpist is only conjectural, that of the bishop is beyond doubt, as portraits of Cardinal Albrecht are ubiquitous: on the front cover in gilded relief, on the inside front flyleaf as an ex libris, in several full-page miniatures depicting his spiritual leadership, and among the historiated initials, where he is presented in prayer. Albrecht’s presence is also proclaimed through his plentiful coats of arms, emblazoned separately in the borders of dozens of text pages, or combined in a full-page display of rank and title flanked by his patron saints, Maurice and Mary Magdalene (fig. 3). Perusing the manuscript, the student of Renaissance art recognizes the signs of a wealthy and powerful patron placing personal aggrandizement ahead of the religious function of the work. But the lavish decoration of the Missale Hallense proclaims another, more sympathetic motivation shared by patron and artist, that is, to produce a stunning example of book craft.

The significance of the Missale Hallense can be measured in economic as well as artistic terms. For this single commission Glockendon received a payment of 500 gulden, a fee so noteworthy that the mathematician, calligrapher, and author Johann Neudörfer refers to it in his 1547 Nachrichten von Künstlern und Werkleuten, a biographical record of Nuremberg artists and artisans.5 Neudörfer, who considered Glockendon “mein lieber Freund” (my dear Friend), adds that Glockendon was a “fertig” (skilled) and “fleissig” (diligent) illuminator who received “auch sonst viel Fürstenarbeit” (a great number of other princely commissions).6 These included not only further work for Albrecht of Brandenburg but also for Duke Johann Friedrich of Saxony, Duke Albrecht of Prussia, the Nuremberg city council, and wealthy patrician families such as Imhoff and Tucher. The Missale Hallense thus represents the centerpiece of a large body of work that to date includes at least thirty bound manuscripts and twenty-three single leaves.7 Although Neudörfer sought to valorize Glockendon’s achievements for posterity, more recent studies of Nuremberg art have associated Glockendon with the Nuremberg Kleinmeister, i.e., the Nuremberg-centered artists who propagated the style of Albrecht Dürer.8 Although the term Kleinmeister is more applicable to the generation of Nuremberg artists known for their small-scale prints, including Sebald Beham, Barthel Beham, and George Pencz, the notion of Glockendon as follower is reasonable because he frequently borrowed compositions from Dürer as well as from other artists.9 The main objective of this paper, however, is to reconsider Glockendon’s imitative works within his artistic and cultural context and examine the circumstances in which those works were produced and received. I am especially interested in his relationship to Dürer, an artist recognized for his self-conscious originality and assertive efforts to protect his work from piracy.10

Glockendon was not a pupil or later follower of Dürer, but a contemporary and colleague, whose relationship to Nuremberg’s most famous artist is documented by correspondence concerning the Missale Hallense. In 1523, when Glockendon was at work on Cardinal Albrecht’s missal, Dürer served as mediator between his colleague and their mutual patron, who apparently had sent an anxious request to Dürer for a report on the illuminator’s progress. In a letter dated September 4 of that year, Dürer explains to the cardinal that the major impediment to the completion of the manuscript is the patron’s delay in payments. Sympathetic to Glockendon’s predicament, Dürer makes a diplomatic appeal for further funding:

…Most gracious lord, on receipt of your gracious letter and request, I at once went to Nikolaus Glockendon about the missal, according to your gracious command. He has not yet got it finished, and he told me that he has still seven large subjects to paint, as well as seven of the largest initials. He would not fix me any definite time when they would be ready. He said that unless some more money were sent him he must lay aside your Grace’s work for want of food, and take something else in hand for he has nothing in the house for his necessities. I could do no more with him in the matter except urge him to carry on the work as far as possible, etc.11

Dürer’s letter indicates a cordial working relationship between the two artists and suggests that Dürer witnessed the production of the Missale Hallense in Glockendon’s shop. This evidence is supported by a 1523 dated drawing by Dürer in Berlin, which served as the immediate model for Glockendon’s full-page miniature of Cardinal Albrecht assisting at a mass celebrated by another bishop.12 The preparatory drawing by Dürer not only attests to the extraordinary customization of the cardinal’s manuscript but also establishes the context for Glockendon’s use of Dürer’s compositions, which he must have borrowed with Dürer’s knowledge and consent. Throughout the Missale Hallense, one recognizes illuminated versions of works of art by Dürer, including twenty-four woodcuts, nine engravings, three drawings, and two panel paintings.13 In the same manuscript Glockendon borrows from prints by Lucas Cranach, Hans Burgkmair, and Martin Schongauer as well as from miniatures by Simon Bening and Jakob Elsner.14 In most cases, Glockendon makes no effort to disguise his source but transforms and interprets it through the masterful handling of pigments.

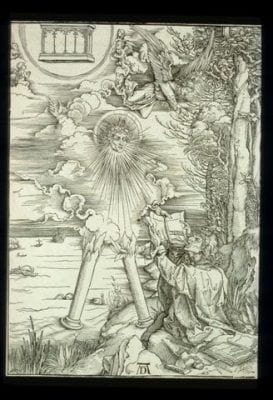

Glockendon’s ability as a colorist deserves mention. In the initials and miniatures of the Missale Hallense he employs one of the richest palettes in the whole of German Renaissance painting. James Marrow, the first American scholar to consider Glockendon’s work, has noted the illuminator’s copies of miniatures by Simon Bening, who also worked on manuscript commissions from Cardinal Albrecht.15 The calendar of the Missale Hallense depends on Bening, and throughout the manuscript one recognizes the reception of Flemish elements, including border decoration in the Streublumen, or strewn-flower style, framing miniatures such as The Trinity (fig. 4). These were likely introduced to him through the work of Jakob Elsner, whose missal for Anton Kress provided the model for The Trinity (fig. 5).16 One can perceive Netherlandish influence in both of these miniatures, which employ the courtly palette of Bruges painting, including rich reds and blues reminiscent of Jan van Eyck. But Glockendon enlivens these with the secondary and tertiary colors associated with Bohemian painting to create a sumptuous interplay of varied and unexpected hues, producing a greater sense of volume and atmospheric space, with only a little reliance on linear perspective. In the miniature The Resurrection (fig. 6), Glockendon closely replicates Dürer’s woodcut of the same subject from the so-called Large Passion (fig. 7), but a comparison between the two works reveals how Glockendon’s exuberant use of color achieves a sense of celebration through shading, gold highlights, and bright hues.

Glockendon’s rendition of The Resurrection from Dürer’s Large Passion recalls his possible alter ego as musician in the Corpus Christi miniature. In Glockendon’s hands Dürer’s authoritative composition becomes an accomplished performance, rephrased and reinterpreted by an artist of different training and sensibility. Evidence suggests that Cardinal Albrecht valued the performative aspect of imitation, especially as pertaining to manuscript illumination. Between about 1525 and 1537 he commissioned three manuscript versions of the same printed book, illustrated with woodcuts by Hans Weiditz, from Simon Bening, Nikolaus Glockendon, and Gabriel Glockendon, respectively.17 Nikolaus Glockendon’s version appears to be a response to Bening’s, and Gabriel Glockendon’s version seems to follow his father’s. Comparison of the illustrations by all four artists reveals variations to this pattern, but in several instances images of the same subject appear to be related according to a progression in which a theme is stated by Weiditz, rearranged by Bening, re-interpreted by Nikolaus Glockendon, and refined by Gabriel Glockendon (figs. 8–11).18 The compositions of seven miniatures from Nikolaus Glockendon’s version are repeated in a series of drawings attributed to the Nuremberg stained glass painter Augustin Hirschvögel.19 Rather than copies, one might justifiably consider such a series of interdependent works of the same subject as musical variations on a theme.

In his book on German limewood sculpture Michael Baxandall uses a musical paradigm to discuss the issue of artistic originality in this period. As an illustrative example, Baxandall outlines the theory of Mastersong, the popular art form of the Nuremberg Meistersinger.20 The Meistersinger contributed to their art by writing new words to old melodies, or Töne, until the 1480s, when “the invention of new personal Töne became more and more the mark of the master.”21 But even after the notion of original Töne gained acceptance, Masters, including the famous Hans Sachs, continued to replicate the classic old Töne as well as the melodies of their contemporaries and their own melodies, over and over again.

Like his contemporary Hans Sachs, Nikolaus Glockendon was capable of creating (and did create) his own compositions. But he preferred to work with pre-established compositions rather than continually to invent new ones. Baxandall explains the standard: “Mastery is the capacity to invent new patterns, and patterns are associated with their inventors; the master will propagate his own pattern, but will feel no shame about using other men’s, particularly the classic ones of the past; lesser practitioners may well settle for working within forms originated by others; the adopting as well as the inventing of patterns is open and avowed.”22

An interesting aspect of this standard is its lack of exclusivity: a master is recognized by his inventions, but they do not constitute inviolable territory. Masters make patterns meant to be copied. Dürer was the acknowledged master of painting in Nuremberg. His compositions were understood to serve as authoritative models for his contemporaries. Glockendon, the acknowledged master of Nuremberg illumination, also produced compositions that served as models for artists such as Augustin Hirschvogel. These artists participated in an artistic tradition that valued interpretation and continuity over invention.

Glockendon’s Missale Hallense, like many masterpieces, whether visual or musical, impresses us with its virtuosity and its fashioning of ambitious patronage. But its technical brilliance challenges us to consider the tacit assumptions we hold and the judgments we make about imitation in Glockendon’s art. How do we understand Glockendon as an artist? He participated in the same culture, lived in the same town, and enjoyed the same patronage as Albrecht Dürer, an artist described as “possessed by an original idea of originality per se.“23 Should Glockendon’s dependence on the work of Dürer and other artists count against him when measuring his artistic accomplishment? Are there universal reasons for artistic imitation or can we discern these as particular to an artist’s historical context, as Baxandall’s paradigm suggests?

This paper will examine Glockendon’s artistic and cultural circumstances in order to better understand the motivations for imitation in his art. It will show that the art and literature of the period employed imitation as normative practice, and that copies and masterpieces in various media were not mutually exclusive works. It will review how printing created a new artistic environment for replication, reconsider Erwin Panofsky’s scholarship that brought prints and German art into the art historical canon, and reevaluate the significance of Albrecht Dürer’s imperial privilege to protect his prints as intellectual property. It will also consider the status of the designing artist and investigate the standards of value for artistic achievement outlined in Johann Neudörfer’s Nachrichten. Ultimately it will reveal a conception of artistic property more tangible than intellectual and re-associate the art of Nikolaus Glockendon and the German Renaissance with the journeyman trades and the manipulation of materials rather than with the tenaciously romantic notion of art as self-expression determined by originality or genius.

Veronica’s Veil

To develop an understanding of imitation in Nikolaus Glockendon’s work, we must first recognize any manuscript illuminator as heir to a tradition that thrived on copies and made no demands on artists to produce something new.24 Furthermore, we must consider the evidence that medieval viewers held invention suspect. Epiphanius of the fourth century, for example, criticizes artists who “lie by representing the appearance of saints in different form according to their whims” and condemns images “set down through the stupidity of the painter…according to his own inclination.”25 As Epiphanius implies, replication was fundamental to the medieval artist’s task: to evoke the sacred authority of established prototypes.

In his classic study of architectural copies of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, Richard Krautheimer supports this view and explains that the power of medieval prototypes was both tangible and intangible: “Both immaterial and visual elements are intended to be an echo of the original capable of reminding the faithful of a venerated site, of evoking his devotion and of giving him a share at least in the reflections of the blessings which he would have enjoyed if he had been able to visit the Holy Site in reality.”26

Medieval imitations of the Holy Sepulchre presupposed an essential optimism that allowed a replica shrine to serve spiritual functions in place of an original exemplar. The churches studied by Krautheimer not only imitated the architectural forms of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre but also included replicas of the tomb of Christ and copies of sacred relics actually preserved in Jerusalem.27 A similar sort of a replica shrine was the most important pilgrimage site in late medieval England—not Canterbury, but the shrine to the Virgin at Little Walsingham, where a stone chapel enclosed an acknowledged replica of the Virgin Mary’s own home.28 In late fifteenth-century Augsburg, the nuns of St. Katherine’s commissioned a cycle of paintings for the walls of their chapter house, in order to simulate a pilgrimage to the seven churches of Rome. Confined to their convent because of the vow of enclosure, they nevertheless received the same papal indulgences for visiting their painted surrogates as did a pilgrim to the actual churches.29

Even in the case of relics what Walter Benjamin refers to as the “aura” or unique presence of an object was nevertheless transferable to a medieval copy, and a recognized imitation could become as sanctified and venerated as an “original.”30 In Byzantium, pilgrims to holy sites brought home eulogia, amulets that contained holy oil and displayed replicas of wonder-working icons that had themselves become equivalent to relics.31 Replicas were also in demand at the fairs of Chartres, where one could purchase copies of the cathedral’s most sacred relic, the tunic of the Virgin. Pilgrims then wore these chemisettes for protection during childbirth or battle.32 A whole genre of pilgrimage manuals developed in the fifteenth century which, like the painting cycle at St. Katherine’s of Augsburg, allowed readers to make a spiritual pilgrimage without leaving home. These manuals, such as one written for the nuns at Windesheim, substituted the mere description of relics for their actual presence and granted indulgences to the reader as if they had seen and prayed in front of relics in Jerusalem or Rome: “Here is the place where Our Lord gave the sudarium [to Veronica]. And Our Lord was very tired and disheveled, spat upon, His holy face covered with blood and sweat; and Veronica went to meet Him, holding her head-shawl, which Our Lord took, and He pressed his holy face against it; and this is the holy sudarium that is shown during the main feast days in St. Peter’s church in Rome.”33

As the last example might suggest, the most commonly copied objects of the Middle Ages were probably not shrines or relics but books.34 In the early Middle Ages, the principal activity of monastic scriptoria was the replication of texts.35 Bede documents this from the beginning of the eighth century, when Abbot Ceolfrith of Wearmouth/Jarrow commissioned three copies of an Italian-made pandect (a Bible bound in one huge volume) known as the Codex Grandior of Cassiodorus.36 Along with the replication of texts came the imitation of images that were considered indispensable components of sacred books. Evidence from the same commission by Abbot Ceolfrith supports this assumption. Preserved in Florence is the Codex Amiatinus, one of Ceolfrith’s three copies. The Codex Amiatinus includes a full-page miniature of the prophet Ezra that points to an Italian prototype (i.e., the lost Codex Grandior) because of its classical approach to light and space.37

In the master narrative of art history, it is customary to present the Middle Ages as a period opposed to and bracketed between classical antiquity and that era’s revival in the Renaissance.38 For example, the above-mentioned miniature of Ezra is often compared to the author portrait Saint Matthew the Evangelist from the Lindisfarne Gospels (figs. 12-13).39 The point of the comparison is to demonstrate the anticlassical approach of the Hiberno-Saxon artist of the Lindisfarne miniature in comparison to that of the artist of the Amiatinus miniature, who regardless of his own roots tried to imitate a classicizing prototype. With respect to imitation, however, this comparison is partly misleading. Although the comparison certainly points to a shift away from illusionism toward a more symbolic approach to visual forms, this pair of images also testifies to the presumption, shared by the “medieval” and the “classical” artist, that religious images should depend on authoritative models.40

Consider for example the miniature Saint Veronica from an early prayer book by Glockendon in Munich (fig. 14). This miniature is included as part of the popular devotion to the cult of the Holy Face, that is the image of Christ’s face on the sudarium, the veil of Saint Veronica, mentioned above.41 As the rubric before the Glockendon prayer text makes clear, this cult promoted the worship of the image of the Holy Face, not just in its “original” presence, as in the relic of the veil of Saint Veronica, but in any artist’s representation of that presence, as in Glockendon’s miniature. The rubric offers generous indulgences, or time relieved from purgatory, to the supplicant who venerates the image, including thirty thousand years for the recitation of a single pater noster before it.42 One can also earn indulgences for simply looking at the image, or by carrying it on one’s person, removed from sight. The rubric makes no distinction between the relic of the Holy Face and the Holy Face in the prayer book. Any version of the Holy Face is the Holy Face.

Veronica’s veil is an important paradigm for understanding imitation within the medieval tradition. The Holy Face was known in the Middle Ages as the vera icon (true image), because it was produced not by human hands, but by the imprint of Christ’s face directly onto Veronica’s veil. The text of the prayer to the Holy Face in Glockendon’s Munich prayer book begins: “Hail, Holy Face of our Savior, in which there shines the form of godly appearance, impressed on a cloth of snow white, given to Veronica as a sign of love.”43

This prayer describes the image as a sign, reflecting the medieval linguistic theory regarding the value of words as surrogates for things. Language, although fallen, was still thought to aspire to the prelapsarian purity of Adam’s speech, in which signifier and signified were the same.44 When discussing images, Neoplatonic theorists used the term methexis (participation), to describe the positive relationship between a sacred relic and an artist’s image of it, inasmuch as any image participates in the “essence” of its model. Early Christian advocates of images used the term overshadowing, taken from Luke 1:35, where the Holy Ghost “overshadows” the Virgin Annunciate, to describe the lasting presence of the model on an image or copy.45 Even the pessimistic Origen of Alexandria (185-254 CE) admitted that after the Fall, Adam never entirely lost the image of God (Genesis 1:26) because God’s image in the human always remains.46 The prayer after Glockendon’s miniature directs the reader, “Look at the Face: there is clearly Christ.”47 The image of the Holy Face attests to the medieval viewer’s confidence in the ability of images to transcend the limits of representation. The sacred presence of the sign is transferred from one copy to the next. The Holy Face is a true image, because it is an image in which there is no difference between itself and the thing it represents.

The value of any single exemplar in this tradition, therefore, was as a carrier of the sign (i.e., the face of Christ). This property of an image as carrier allowed replicas of relics or venerated images to function in place of their models, because the image or copy was understood as a means of witness to a sacred presence. Peter Parshall has discussed the term imago contrafacta used in inscriptions by Israhel van Meckenem on two of his engravings from the late fifteenth century.48 The term contrafactum has an English cognate, “counterfeit,” but Meckenem and other artists used it nonpejoratively to mean a copy that bears witness. Both Meckenem engravings replicate the Imago Pietatis, the mosaic image of Christ as the Man of Sorrows, preserved as a relic of Saint Gregory’s Mass at the Church of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme in Rome.49 The intent of Meckenem’s prints is to offer the viewer-supplicant the same fourteen thousand years of indulgence against purgatory as one would receive for devotions performed before the Imago Pietatis relic in Rome. The Meckenem prints differ in size and decorative detail, but such differences had no impact on the effectiveness of either image, as long as each was identifiable as a copy of the sacred relic.

The function of an imago contrafacta as witness actually relaxes the relationship between model and copy and allows room for minor adjustments. Compare, for example, The Man of Sorrows by Glockendon from the Sattler Prayer Book (fig. 15) with its exemplar in an engraving by Dürer (fig. 16).50 In both images, Christ as the Man of Sorrows stands before the base of the Cross and displays his wounds. At his feet lie various instruments of the Passion. In Dürer’s engraving these include the scourge, the cloak, the dice, and the sponge of vinegar. In Glockendon’s miniature, the artist adds to these the spear of Longinus, a whip, nails, and tongs. Glockendon also enhances the image with a background landscape and an elaborate architectural framework.

Glockendon’s embellishments to Dürer’s Man of Sorrows follow a strategy typical of imitation in medieval sacred art. The artist’s purpose is not to differentiate his work from another’s for the sake of individual style or originality. Nor do Glockendon’s additions manifest the late Gothic horror vacui. Glockendon is simply changing his model to suit the function of his image as a devotional aid to a prayer text. The rubric not only explains some of the deviations from the model but also clarifies the specific function of the image in its devotional context:

Whoever while before the picture of the Man [of Sorrows] calls upon the Mercy of God, speaks or prays three Our Fathers and as many Ave Maria’s, will by decree of Pope Clement receive 34,040 years indulgence. And if the instruments of the Passion of Christ are also depicted, the indulgence is doubled. [Moreover,] each instrument has a special indulgence; accordingly speak the prayer with reverence, and this indulgence is granted by the worthy Father Nikolaus, Abbot of the Monastery of Our Lady in Florence.51

The purpose of this devotion is to obtain indulgences (Ablass), or time credited against purgatory.52 The rubric demonstrates the power of the image as a devotional object, which Glockendon enhances by including the instruments of the Passion, since twice as many years indulgence can be earned if the instruments are included. Each instrument further earns a special, unspecified indulgence, perhaps commonly known to the late medieval supplicant.

Once Glockendon’s motivations for altering his model become apparent, it is possible to explain some of his other revisions, such as the handling of Christ’s loincloth, which billows up around the figure rather than binding it, as in Dürer’s version. This alteration appears to indicate Glockendon’s preference for late Gothic stylistic conventions.53 But it may also serve to fetishize the loincloth as another object on which meditation and prayer for indulgences can be focused.54 Glockendon’s addition of a suggestively Bavarian landscape serves to emphasize the immediate presence of Christ’s sacrificial body in the supplicant’s world. The architectonic framework encloses the image in a carved, bejeweled shrinework, as if it were part of a reliquary, and further contributes to the devotional power of the image, which persistently prevails from one “witness” to the next.

Boccaccio’s Tale

In the late medieval period, the practice of relying on models while constantly changing them to suit new contexts is characteristic not only of art but also of literature. Gerald R. Bruns associates this practice in literature specifically with the cultural context of the medieval manuscript. Bruns draws “a distinction between two kinds of text: the closed text of a print culture and the open text of a manuscript culture.” Bruns explains print culture and its emphasis on authorization: “Print closes off the act of writing and authorizes its results….There are numerous (numberless) complicated forces of closure in a print culture….What is printed cannot be altered—except of course, to produce a revised version or edition.”55

In the late fifteenth century, one witnesses what Bruns describes as “forces of closure” emerging in the first protective privileges (the forerunners of copyrights). Glockendon’s adaptation of prints and paintings by his sixteenth-century contemporaries, however, depended on his participation in an audience that still recognized “the open text of a manuscript culture.” Bruns describes this text as one that “opens outwardly rather than inwardly, in the sense that it seems to a later hand to invite or require collaboration, amplification, embellishment, illustration, to disclose the hidden or the as-yet-unthought-of.”56

Bruns recalls late medieval examples of such an open text, including those variations of tales passed among writers, including Boccaccio, Chaucer, and Petrarch. Chaucer’s Troilus and Crysede is infamous for its “plagiarism” of Boccaccio’s Il Filostrato and for its bogus citation to the antique authority Lollius. Yet Bruns understands Chaucer’s deception as a narrative strategy in which the author “chooses to conceal his originality,” preferring to speak “with a fictional authority that has been carefully constructed.”57 Chaucer’s motivations for the retelling of Boccaccio’s tale included the translation from one vernacular language into another. Bruns explains the medieval concept of translatio (literally, turning), as it relates to the concept of the open manuscript text:

…in a manuscript culture to translate means also the turning of a prior text into something more completely itself, or something more than what it literally is. I can refine this somewhat by saying that in a manuscript culture the text is not always reducible to the letter; that is, a text always contains more than what it says, or what its letters contain, which is why we are privileged to read between the lines, and not to read between them only but to write between them as well, because the text is simply not complete—not fully what it could be, as in the case of the dark story that requires an illuminating retelling.58

In a woodcut from Dürer’s illustrated Apocalypse one discovers medieval translatio in literal terms (fig. 17). John, author of the Revelation, is commanded by a fearsome angel to eat a book. Although the subject results in a rather astonishing visual image, the angel’s point is that John must first digest one sacred text in order to write another. Glockendon digested the prints of Dürer and other artists, turning each black-and-white composition into “something more completely itself, or something more than what it literally is.” To Glockendon and his patrons, an image in print offered a “dark story that requires an illuminating retelling.” Glockendon’s art can be compared to what Bruns describes as “the grammarian’s art of embellishment, ” which “adds lustre” and “illuminates what is hidden in the original,” which “is, in any case, tacitly unfinished.”59

The concept of finishing is important to understanding imitation in the art of manuscript illumination. The common division of labor in a scriptorium or an illuminator’s shop usually produced a single work of art as a collaborative project. The painted decoration of a manuscript came late in the bookmaking process, after the cutting, ruling, and layout of the pages. The program of illustration could be arranged only after the scribe’s organization of the text.60 Decorated initials could be added only after the layout of the text was certain to the letter, and sometimes not until the script was completely in place. The manuscript wasn’t finished until the work of the illuminators was done.

As Douglas Farquhar points out, the illuminators’ traditional practice of working from model books contributed to repetition in illumination.61 Working from existing patterns also places the illuminator in the position of finisher. In Glockendon’s work, however, the model book was largely replaced by contemporary prints. Glockendon’s painted versions of printed images reflect a contemporary taste for hand-colored prints, works often misunderstood by modern historians. Although reviled by Erasmus, the application of pigments to prints was a common sixteenth-century practice, as demonstrated by a 2002 exhibition at the Baltimore Museum of Art. In the catalog to the exhibition, Susan Dackerman challenges modern notions of originality that have denigrated the work of Briefmaler (print-colorists).62 Briefmaler such as the Mack family of Nuremberg added colors to prints, in the same tradition as German artists who added gold and pigments to sculpted altarpieces. Tilman Riemenschneider’s now dispersed altarpiece from Münnerstadt was painted and gilded by Veit Stoss some ten years after its completion. Consistent with his contemporaries’ indifference to originality, Riemenschneider was paid 145 gulden to design and carve the altarpiece, but Stoss received 220 gulden to paint it.63 The record of payments on the altarpiece from Münnerstadt not only demonstrates how collaboration flourished in this period but also emphasizes how the process of translatio could increase the value of a work.

Bruns cites another example of literary translatio in Petrarch’s Latin version of the “Tale of Griselda,” which Petrarch, like Chaucer, borrowed from Boccaccio’s Decameron.64 Petrarch’s work compares with Stoss’s gilding of Riemenschneider’s altarpiece, or with Glockendon’s embellishing the compositions of Dürer and other printmakers, because it involves “finishing” a work of lower value (an entertaining story in the vernacular), in order to turn it into a work of elevated style (a moralizing treatise in Latin): “Petrarch translates Boccaccio’s story not only laterally into a different tongue but upwardly into a more noble style (stilo nunc alto), and this noble style stipulates in turn large amplification of matter….Petrarch transposes the story from the locality of the vernacular to the universality of Latin, which is a way of finishing the story…a way of enshrining the story.”65

Several authors translated Boccaccio’s tales into German. Heinrich Steinhöwel (ca. 1411-1479) produced Griseldis, first printed by Günther Zainer of Augsburg, to appeal to a popular audience. It became a best-seller, with nine fifteenth-century printings and at least eleven more in the sixteenth century.66 Niklas von Wyle (ca. 1415-1479), inspired by his friendship with the humanist Enea Silvio (Pope Pius II, r. 1458-64), produced a miscellany of works called Translatzen, first printed by Konrad Fyner at Esslingen in 1478.67 A former Nuremberg Stadtschreiber (city secretary), who also held the position of boarding-school teacher at Esslingen, Wyle translated this collection of “lustig und kurtzwilig” (amusing and entertaining) tales and short treatises from Latin into German, including one tale originally from theDecameron, “Guiscard und Sigismunda.” In a forward to this tale Wyle associates his work with Petrarch’s translation of “Griselda.”68 As part of a career ambition to develop Kunstprosa (an artful, if not artificial, literary style of writing), Wyle intended to refine written German through the adaptation of humanist themes, classical rhetoric, and Latin syntax. Although Wyle translated from Latin into a vernacular language, he saw translatio as an elevating process that resulted in “guot zierlich tütsche…und nit wol verbessert werden möchte” (good, elegant German that could not be improved upon).69

As a panel painter and internationally renowned artist, Dürer may have been considered by his peers to be Glockendon’s professional superior. But manuscript illumination was clearly a more expensive, and arguably a more “zierlich” medium of text illustration than that of prints. Part of Glockendon’s imitative task as an illuminator was to elevate the prints of Dürer and others into the stilo nunc alto, or “heigh stile,” of illuminated manuscripts. I have mentioned previously how Glockendon’s buoyant handling of colors served to transform Dürer’s Resurrection into a work of celebration. Glockendon’s sumptuous pigments highlighted with gold also served to elevate Dürer’s woodcut in terms of style. This stylistic ennoblement, moreover, was a basic assumption of his imitative enterprise. For Glockendon and his audience, artistic imitation was not associated with degraded results. On the contrary, an imitative work of the late medieval tradition could be considered continuous with or even elevated from its model or source.

Gutenberg’s Commerce

Between the years 1450 and 1454 Johannes Gutenberg of Mainz printed from movable type about 180 copies of the double-column, 42-line Bible that created a revolution in bookmaking and related artistic media.70 It was no accident that Gutenberg chose the Bible as the text to announce his invention in the marketplace. To produce a complete Bible in multiple copies was a radical advertisement of what his new process could accomplish.71 Before the invention of printing, the text of the Bible was often codified as constituent parts, such as the Psalter, the Gospels, the Revelation (Apocalypse), or produced in paraphrased versions, such as the Bible Moralisée. Gutenberg’s invention, however, put printers in a position to respond, perhaps even to help generate, the growing demand for the unabridged Bible. The advantage of printing in this context left many illuminators to rely on printers for work.72 It is important to recognize that the work of printers and printmakers in this period significantly influenced the work of illuminators. Few scholars have studied the impact of printing on book illumination in post-Gutenberg Germany. Eberhard König, however, has demonstrated that the change in conditions in book production in this period pressured illuminators to accommodate standardization and replication in their work.73 Although illuminators were often called upon to decorate early printed books, the production methods of Gutenberg set a precedent that precluded extensive programs of painted illustration. Some preserved copies of the 42-line Bible have illuminated initials and borders, but “following its example, not a single incunable printed in Germany provided space for miniatures.”74 While printing methods restricted programs of illustration, the work that was available for illuminators compelled them to keep pace with new schedules of production that discouraged customization. Even beyond practical circumstances, printing reinforced an aesthetic that rejected pictorial innovation. König cites the example of a talented but anonymous illuminator who worked at Mainz for Johannes Fust, Gutenberg’s business partner. This anonymous artist added illuminated decoration to several printed books, including two copies of the 42-line Bible preserved at Burgos and New York, respectively. According to König, this illuminator was obviously accomplished but for the sake of standardization and consistency suppressed his individuality as an artist, “even if he had to give up what we might regard as his real quality.”75

In fifteenth-century Holland single-leaf prints produced a measurable impact on the market circumstances for book illustration. James Marrow discusses three different artistic strategies that Dutch illuminators experimented with to gain competitive advantage over printmakers.76 The first of these was to produce single-leaf miniatures that they sold as independent images to be inserted into books at their owner’s discretion. This strategy freed the illuminators from the burden of commissions for complete manuscripts and enabled them to compete with contemporary printers who sold woodcuts and engravings as independent, self-contained images. The second strategy the Dutch illuminators used was to change their painting technique from polychrome to grisaille. A picture in grisaille looked more like a printed picture and was cheaper to produce in terms of both materials and labor. The third strategy used by the Dutch illuminators was replication. They used replication in different ways. For example, some created assembly-line systems of production that included tracing, so that one shop could produce multiple copies of the same image in the manner of the printmakers. Others copied the work of printers—not only prints but also printed books. The Harley Hours in the British Library (Ms. 1662), for example, may be a manuscript copy of a printed book illustrated by the so-called Master of the Berlin Passion.77 There are in fact many manuscripts from the fifteenth through the sixteenth century that are copies of printed books, and many examples of hybrid works that demonstrate the entrepreneurial spirit of the artists who worked in book illustration during this period.78

Georg Glockendon the Elder, Nikolaus’s father, was just this sort of entrepreneurial artist. According to Neudörfer, Georg illuminated choir books, missals, and Wappenbriefe (official charters authorizing coats of arms). He also ran a large business in gemalte Briefe (hand-painted documents and prints).79 Works preserved by Georg include not only (attributed) illuminated manuscripts but also several cartographic projects in which he collaborated with Erhard Etzlaub: a hand-painted pre-Columbian globe of the world, a 1492 printed map of Franconia, and a printed (some issues hand-colored) map of central European routes to Rome for the Jubilee year 1500.80 Georg also published a printed almanac, a 1509 printed translation of Jean Pèlerin’s book on the art of perspective (translated by Georg’s son Johann), and various printed and hand-colored broadsheets. Neudörfer mentions that Georg’s sons and daughters all helped out in his busy workshop, and that his sons Nikolaus and Albrecht became “berühmte Illuministen” (famous illuminators).81

There was at this time a great deal of artistic innovation going on, but it was innovation based on competition and artistic exchange, not on artistic individuality: “The pace of artistic interchange quickened considerably in Northern Europe during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, in parallel with changes in its nature….For just as the appearance of the printed word led to an intensified and broadened commerce in ideas, so the development of printed images, both in woodcuts and engravings, led to an expanded commerce in visual ideas.”82

The commerce in visual ideas discussed above by Marrow, included not only patterns and compositions but also new methods of production, and “a new attitude toward the use and reuse of images…with all that phrase implies about the easy dissemination and replication of artistic ideas.”83 Illuminators were enthusiastic participants in this commerce, for the advent of printing forced them to face the unprecedented challenge of a new method of book illustration and a new kind of book. This new book rapidly asserted itself in the marketplace, where it sold at high volume for a low price.84 An eventual response from sixteenth-century illuminators would be to change their market strategy and present their product as a high quality alternative to the printed text. But illuminators were trained in a tradition that presumed replication, so they also sought to compete with printers in the wider market for illustrated books and documents, which until the invention of printing had exclusively belonged to them.

Against this background we can begin to measure Nikolaus Glockendon’s own survival skills in the tightening market for book illumination. Although he did not publish printed materials like his father and brother, or use grisaille technique like the Dutch illuminators, he did produce single-leaf miniatures, many of which appear in manuscripts made for Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg. Cardinal Albrecht not only commissioned and collected complete manuscripts but also purchased dozens of single-leaf miniatures by Glockendon, Simon Bening, and Sebald Beham.85 These miniatures were inserted into books made for the cardinal at his Halle scriptorium, headed by George Stierlyn, a scribe who painted initials and borders but not miniatures. Stierlyn’s manuscripts, such as a Book of Hours (Ms. 9) at Aschaffenburg, comprise outsourced projects with illustrations by artists who possibly never even met each other (fig. 18).86 Not surprisingly, the single-leaf miniatures produced for such manuscripts often consist of compositions based on prints. The demand for single-leaf miniatures in the sixteenth century represents evidence that illuminated manuscripts made after the invention of printing competed with printed books. Manuscripts retained a special attraction for wealthy patrons as luxurious, but not necessarily unique, objects. Cardinal Albrecht’s manuscripts were not only expensive and prestigious objects of ownership but also repetitions of works of art and texts that he already owned in print. Book illuminators retained a market share after the advent of printing, not because of their product’s singularity but rather because of their ability to compete in the new economy created by Gutenberg.87

Panofsky’s Project

In order to completely come to terms with the context in which Nikolaus Glockendon thrived as an imitator, one must address the issue of individuality and self-consciousness associated with Renaissance art in general and with Albrecht Dürer in particular. Erwin Panofsky, for example, explained that Dürer preferred producing prints to paintings because, “the graphic media were the most appropriate means of expression for a mind dominated by the idea of ‘originality’.”88 To be sure, Dürer developed an assertive sense of artistic territory, as he actively sought to protect much of his printed work from fraudulent replication. But we should also recognize that Panofsky, whose study of Dürer still dominates the scholarship of this period, saw it as his mission to elevate the history of art in Renaissance Germany to a level of scholarly recognition comparable to that of Renaissance Italy.

In her work on painted prints, Susan Dackerman complains about the “unexplored contradictions” in Panofsky’s “medium-bound” art history that depends on a hierarchy of media, single authorship, and view of the artist as a unique creative force: “Modern notions of originality therefore cast the work of the (often unknown) colorist as an adulteration of the printmaker’s work. The same conception of originality, however, was not at play during the Renaissance, when workshop practices dominated the production of printed images.”89

Modern scholarship often overlooks the fact that many of Dürer’s prints were created neither as single-leaf prints nor as compendia of images but as components of workshop-produced illustrated books. Recently, however, a 2008 exhibition at Nuremberg highlighted Dürer’s work as a publisher and book illustrator.90 The exhibition included the three large-format volumes that the artist referred to as “die drei grossen Bücher” (the three large books): the so-called Life of the Virgin, Apocalypse, and Large Passion.91 Also included in this exhibition were Dürer’s instructional books for artists, two copies of the so-called Small Passion, title pages, ex libris plates, and various marginalia. Dürer also contributed to the marginal decoration of a printed prayer book for Emperor Maximilian I (not included in the exhibition) and had plans to publish an illustrated prayer book known as the Salus Animae, which, however were never fulfilled.92

Dürer published the first of his books, the Apocalypse, in 1498, with a Bible text set in type borrowed from his godfather Anton Koberger.93 Panofsky, in seeking to emphasize the dominating presence of Dürer’s illustrations, describes their relationship to the text as such: “Dürer…wanted…a continuous yet brief series of pictures neither interrupted by the text, nor inserted in the text, nor, of course, interspersed with the text. He therefore reserved the front of his huge pages for woodcuts free from inscription and printed the text on the back.”94

Wishing to free Dürer’s prints from their role as illustration to a text, Panofsky elevates them to a level of autonomy traditionally reserved for panel painting. In the effort to further his agenda, however, he misrepresents Dürer’s work, suggesting that the artist had asserted his sense of self-expression over scripture itself. Panofsky gives us the impression that the illustrations to the Apocalypse were actually single-leaf prints with complementary text printed on the verso. The text on the back of each illustration of the Apocalypse, however, corresponds with the image on the following folio, not the image on the recto side of the same folio as Panofsky implies. The relationship between text and image only works if the folios are bound together in a codex format. The text even includes a rubric for the illustration on the following page, such as “sequitur tercia figura” (here follows the third figure) The pictures are indeed “interspersed” with the text. This format applies to all the “drei grossen Bücher” as well as to the Small Passion.

By 1511 Dürer had printed editions of the Apocalypse, the Large Passion, the Life of the Virgin, and the Small Passion with an imperial privilege of protection against unauthorized copies. Although an early forerunner of artistic copyright, Dürer’s privilege should not be understood in modern terms. I translate Dürer’s privilege from the Latin as follows:

Hey, you perfidious thief of other’s work and talent!

Beware not to lay a reckless hand on this our work.

Then know, by the glorious Emperor of the Romans,

Maximilian, are we entitled, that no one may dare

reprint these pictures with counterfeit blocks, or sell

them already printed, within the borders of the Empire.

But if you, out of contempt or criminal greed act to

the contrary, know surely that you must submit to the

confiscation of your property and great penalty.95

In his book on Albrecht Dürer, Joseph Koerner interprets Dürer’s privilege as “a warning to all copyists,” who might steal Dürer’s “unique pictorial invention.” Koerner builds on Panofsky’s project in order to invest Dürer with an essentially modern self-consciousness.96 Koerner’s views on originality are informed by those of Harold Bloom, whose literary theory presupposes the anxiety of an epigone burdened by the accomplishments of an established master.97 Considering, however, the language of the privilege and the evidence regarding Nikolaus Glockendon and his artistic and professional relationship to Dürer, we may question whether such a modern sense of originality is represented in Dürer’s privilege. If Koerner is correct, Dürer should have regarded Glockendon as a competitor and thief of his work (labor) and talent (ingenium).98 But we know instead that Glockendon worked with Dürer’s approval, as attested to by the previously discussed documentation concerning the Missale Hallense. The letter from Dürer to Cardinal Albrecht and extant preliminary drawing by Dürer make clear Dürer’s supportive position, even though the manuscript referred to is filled with copies of Dürer’s imperially protected prints. We also know that Glockendon copied Dürer’s compositions in other manuscripts, including the prayer books in Modena (fig. 10) and Munich (figs. 14–15) previously discussed. In spite of the privilege’s claim to protect the artist’s labor and talent, Dürer did not object to Glockendon or any other artist copying free-hand from his prints. What he did object to were forgeries, pictures printed suppositiis formis, i.e., on “counterfeit blocks.”99 My translation of suppositiis formis, departs from Koerner’s “spurious forms,” and I believe the difference between these translations is significant. “Forms” in the artistic vocabulary of sixteenth-century Nuremberg were not compositional forms but negative forms, such as the molds used for bronze casting or the woodblocks used for printing.100 A Formschneider was a craftsman who cut woodblocks, not an artist who carved designs. The technique for carving a woodblock for printing or a wooden model for casting was the same: the artist cut away the negative space from the form. Artists such as Peter Flötner made both woodcuts and plaquettes cast in metal from wooden forms.101

Dürer developed a new sense of proprietary rights about his work, not because he had developed a modern sense of artistic originality but rather because he literally owned the blocks or plates from which new copies could be made. Before the invention of printing, a medieval artist did not acknowledge any ownership of his work because he retained no physical ownership of it. Dürer was protecting something made in his shop that belonged to him, and he could prove it. Dürer’s privilege warns that the punitive measures to be taken against counterfeiters include the confiscation of property, literally, “the goods” (bonorum), i.e., the forged works of art. The focus is on the process and product of making, not on the ideas or intellect behind it. The property under protection is material, and its violation as artistic territory is to be paid for in kind. This sense of artistic property was also demonstrated in the litigation of 1519-20 between Gerard David and his assistant Ambrosius Benson. The dispute involved two trunks belonging to Benson, the contents of which included patterns that David alleged belonged to him. The patterns at issue, however, were physical property, not intangible designs.102 The famous case against Christian Egenolff for copying botanical illustration was brought in 1533 by the publisher Johann Schott, who owned the woodblocks and had received an imperial privilege that protected his ownership. Hans Weiditz, the artist who designed the illustration, was not involved in the case because he had no ownership at stake.103

Dürer’s notion of artistic property can be measured against the status of the designing artist in a collaborative work known as the Silver Altarpiece of King Sigismund I of Poland, made for the cathedral of Cracow in the years 1531-38.104 Hans Dürer, Albrecht’s brother, created the designs for this work, while Georg Pencz executed the paintings on the exterior of the wings. Georg Herten did the wood carving, and the sculptor Peter Flötner prepared the wooden models and figures for the brass casts, which were made by Pankranz Labenwolf. The silver reliefs were produced by the goldsmith Melchoir Baier. The price of the finished altarpiece came to the exorbitant sum of 5,801 gulden, 8 groschen.105 The painter Georg Pencz received 290 gulden for his work, and the wood-carver Georg Herten received 30 gulden. Hans Dürer was paid 12 gulden for his designs.

One could interpret these terms of compensation as an indication of the inferior talents of Dürer’s brother. Hans Dürer, however, held a prestigious position as court painter to King Sigismund at the time. As court painter Hans Dürer may have received a regular salary, but the unimpressive fee for his contribution to a work of such great value reflects a general view regarding artists’ designs in sixteenth-century Germany. The relative devaluation of Hans Dürer’s work, moreover, is related to the limits of ownership that an artist assumed concerning his work in this period. The language that declares his brother Albrecht’s privilege as based on labor and ingenium is inflected with both a sense of hard-toiled craftsmanship and of gifted intellect. The word labor in this context represented an alternative to ars (skill) or manus(hand), all of which index the labor and physical aspect of artistic production.106 Even as Albrecht Dürer aspired to the humanist values associated with ingenium, the rights of the deserving artisan motivated his privilege and prevailed among sixteenth-century German artists, including those who collaborated on the Silver Altarpiece.

Further evidence of the notion of artistic property in this period can be discerned from an incident preserved in Vasari’s Lives. Vasari records that in 1506 (before the date of the privilege) Dürer brought a lawsuit against Marcantonio Raimondi for publishing engraved copies of woodcuts from the Life of the Virgin.107 The agreement reached by the Venetian court was that Marcantonio could still issue copies of Dürer’s prints, but not with Dürer’s monogram. Koerner feels that the function of Dürer’s monogram, or Handzeichnung, “would have been precisely to claim authorship for the composition.”108 I would, however, reconsider this assumption. The monogram protects property, but that property may be more material and technical than intellectual. Rather than assume that Dürer wanted to stop Raimondi’s copies altogether, we should consider that he may have received exactly the judgment he wanted, which was to stop works made suppositiis formis that buyers might confuse with those made by his own hand or in his own shop. Raimondi himself may have been happy to receive a ruling about the matter, as there are engravings by him with both Dürer’s and his own monogram, as if he wasn’t really sure how to identify copies of signed prints.109 In her discussion of Marcantonio’s copies after Dürer, Lisa Pon suggests that the Italian engraver’s use of Dürer’s monogram “was not so much a plagiarist’s blunder, but…a publisher’s acknowledgement of a model that was in any case not protected against copying in Venice.”110 Although Pon characterizes Dürer as “a possessive artist-author,” she also recognizes that Dürer’s monogram and privilege may have functioned separately, as the privilege was “granted more on the grounds of his function as the publisher of the book, rather than as the creator of the images.”111 Recall that Albrecht Glockendon, Nikolaus’s brother, served as publisher for the prints of other artists, including Sebald Beham and Erhard Schon, and advertised a privilege that protected his rights, not theirs.112 Because privileges granted during this period sometimes protected vendors who had little or no part in the creation of the products they offered for sale, the use of the modern term Urheberrecht (copyright, literally creator-right) in this context seems especially anachronistic.113

In her study of Italian printmakers, Evelyn Lincoln finds that even in Italy concepts of authorship and ownership during this period were at best elastic: “It is obvious, in the vocabulary of the print personnel and in the subject matter of the prints, that originality was not located in a notion of absolute novelty as to subject matter or even medium; neither was authorship fixed in any single image or claimable by a single person.”114 Vasari himself held no disdain for imitators. His Lives includes a flattering biography of Giulio Clovio, the illuminator who copied works by Michelangelo and other artists (including Dürer) to create dynamic miniatures and elaborate border decorations in a thoroughly Italianate style. Vasari describes in great detail the Book of Hours Giulio completed for Cardinal Alessandro Farnese in 1546 and even celebrates the illuminator’s imitative gifts: “…Don Giulio has surpassed in this field both ancients and moderns and…has been in our times a new, if smaller, Michelangelo.”115 Some of the miniatures Guilio created are indeed smaller Michelanglos. Others are illuminated versions of Dürer prints, comparable to miniatures by Nikolaus Glockendon (figs. 19-21).

Neudörfer’s Snail

According to Gerald Strauss, the use of punch marks or stamps as a code of authenticity was regulated in Nuremberg manufacturing.116 In the late fifteenth century, for example, the city produced regulations regarding marks identifying armor, and in 1498 stipulated that the official Beschau (viewing mark) was to be the half-eagle arms of the city.117 Although extant works from before the mid-sixteenth century indicate that master’s marks were not consistently applied, Nuremberg goldsmiths also used various punch marks to identify themselves and/or their city. Nikolaus Glockendon’s frequent use of a reverse N in his signature (NG) plays off the recognition of the reverse N as a mark of Nuremberg craftsmanship.118 The artist’s substitution of the cipher of his town for the cipher of his name not only associates his work with that of the trades but also reveals the corporate and commercial inflection of a signature that a modernist might read solely as an index to a personality. Many miniatures by Glockendon are not signed, moreover, and it is not at all clear that his or even Dürer’s signature should be interpreted in the same manner as that of a modern artist. Nuremberg painters, illuminators, and printmakers were members of the unregulated “free” crafts (freien Kunste) and did not enjoy the same legal status as those belonging to the “sworn” or regulated crafts (geschworne Handewerke).119 Beginning in 1477 and throughout the sixteenth century Nuremberg painters, illuminators, and Briefmalerrepeatedly petitioned the city council for regulated status.120 Dürer’s insistence that his monogram be protected should be understood in this context: a claim to be deserving of the same respect as a master of any sworn trade.121

A treatise written at Nuremberg in 1547 associates art with the journeymen trades. The author, Johann Neudörfer, represents the culturally blurred distinctions between art and craft in his Nachrichten von Künstlern und Werkleuten.122 Neudörfer’s Nachrichten consists of a collection of short biographies of about eighty Nuremberg artists and artisans who worked during the sixteenth century. It includes essays about stonemasons, wood-carvers, bronze-casters, goldsmiths, bell-makers, fountain-makers, painters, wood-block cutters, scribes, illuminators, coats of arms-makers, stained-glass painters, cabinetmakers, organ builders, lute-makers, book printers, and papermakers, as well as locksmiths, clock-makers, cobblers, embroiderers, furriers, carpenters, plumbers, screw-makers, gear-makers, eyeglass-makers, wagon-makers, scales-makers, and coin-makers. Neudörfer’s discussion of these producers reveals specific values regarding artistic labor and talent.

Neudörfer’s subjects include Nikolaus Glockendon and Albrecht Dürer, as well as Nuremberg artists such as Veit Stoss, Hans von Kulmbach, and Georg Pencz. With carpenters and clock-makers they appear to have one thing in common: they are all craftsmen, skilled individuals who work with their hands. Neudörfer, himself a master calligrapher who collaborated with several of the artists he writes about, reveals his appreciation for the work of the hand in several individual biographies.123 He exclaims, for example, that the stonemason and sculptor Adam Kraft was ambidextrous: “Er war mit der linken Hand zu arbeiten gleich so fertig als mit der rechten…”124 One sculptor, named Simon with the Lame Hand, is praised for his work as sculptor, goldsmith, and clock-maker, and maker of all sorts of other “künstlichen Ding,” (skillfully-crafted things) in spite of a crippled hand.125 To emphasize the manual skills of the wood sculptor Peter Flötner, Neudörfer notes Flötner’s ability to carve intricate figures on small natural objects: a cow horn with 113 different faces of men and women and a piece of coral with little animals and mussels, so that they appeared to grow on it.126

Along with the skilled hand, Neudörfer valued a craftsman’s ability to transform materials. In his account of the eyeglass-maker Hanns Ehemann, Neudörfer relates a story of how this craftsman once took a Venetian drinking glass, threw it on the floor, burned the pieces, stretched them in the fire into a sheet thin as paper, and turned them into a pair of crystal eyeglasses.127 With filial pride he presents an account about his father, Stephan Neudörfer, a furrier who once received a job from a rich Venetian merchant requiring him to soften a sable pelt, in order that the man’s wife could wear it around her neck. The elder Neudörfer treated the pelt and achieved such remarkable results that the merchant was able to pass the pelt through his seal ring.128 Neudörfer also praises the ability of Hieronymus Gärtner, known for his work in architecture and water engineering, to carve tiny pieces of wood into lifelike objects, such as a cherry supporting a mosquito with wings so delicate they would move if someone blew on them.129 He gives similar credit to Wenzel and Albrecht Jamnitzer, goldsmiths who once presented him with a silver snail, cast with tiny flowers and plants that would also respond to a breath of air.130 The Jamnitzer brothers were renowned for this sort of work, in which they cast small animals and plants directly from real specimens. The life-casting process involved extraordinary skill with materials, but no drawing or design, and was praised not only by Neudörfer but also by Vasari in the preface to his Lives.131 These authors, craftsmen in their own right, did not view life casting as some form of cheating the artistic process. For them life casts “demonstrated the powers both of nature and its transformation by human artifice.”132 A literal copy of a specimen from nature was valued just as was a well-executed copy of another’s artist’s work.

Glockendon’s Art

The purpose of this essay has been to develop a culturally and historically sensitive consideration of the art of Nikolaus Glockendon of Nuremberg. I have presented Glockendon as an artist of high technical achievement, including his masterpiece of manuscript illumination, the Missale Hallense of Albrecht of Brandenburg. But because of Glockendon’s reliance on the compositions of Dürer and other artists, I have also considered a series of issues in order to conceptually frame the role of imitation in Glockendon’s work. I have presented this work as a continuation of medieval tradition, exemplified not only in the regenerative nature of sacred imagery but also in the transmission, re-creation, and reinterpretation of borrowed works in secular literature. Turning to the historical circumstances of the fifteenth century, I described the impact of the invention of printing on illumination, in so far as it compelled illuminators to participate in the commerce of book production with its new demands for replication and standardization. Focusing on Glockendon’s more immediate context, I examined Glockendon’s professional relationship to Dürer in order to challenge a notion of artistic originality central to Panofsky and Koerner’s presentation of the Nuremberg printmaker as the epitome of Renaissance genius. Consequently I evaluated the terms of artistic property presented in Dürer’s imperial privilege and compared these with projects by contemporary artists to reveal a notion of artistic property more tangible than intellectual, with little regard for “original” designs. I then measured contemporary standards of artistic value in the essays of Johann Neudörfer, who associated art with the journeyman trades and prized the skill of the hand and the manipulation of materials, even in the absence of drawing and design.

Ultimately my study of Glockendon’s imitative practice supports Baxandall’s premise that a fuller understanding of German Renaissance art necessitates the discovery of values particular to a culture different from our own. The subjective application of modern (and modernist) notions of originality to the art of other periods and cultures, needs to be replaced by the adjustment of our responses to the reception of images appropriate to an artist’s own time and place.