English translation of E. J. Sluijter, “Over Brabantse vodden, economische concurrentie, artistieke wedijver en de groei van de markt voor schilderijen in de eerste decennia van de zeventiende eeuw,” in Kunst voor de markt, ed. R. Falkenburg, J. de Jong, and B. Ramakers, Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 50 (1999): 112-43. The text was translated by Jennifer Kilian and Katy Kist with footnotes translated by the author.

This essay presents observations on how and why the number of painters and the production of paintings in Holland increased so spectacularly around 1610. It also discusses the technical changes, the economic competition, and the artistic emulation related to this increase. It is argued that the sudden wave of inexpensive paintings from Antwerp that flooded the Dutch art markets in the first years of the Twelve Years Truce – paintings which seem to have been bought avidly by immigrants from the Southern Netherlands in particular – functioned as a booster. Decorating the house with a variety of rather inexpensive paintings, something the immigrants were already familiar with, caught on with the native population. Second generation immigrants took advantage of this profitable gap in the market and competed with the imported works by producing paintings with similar techniques and subjects, but of a higher quality.

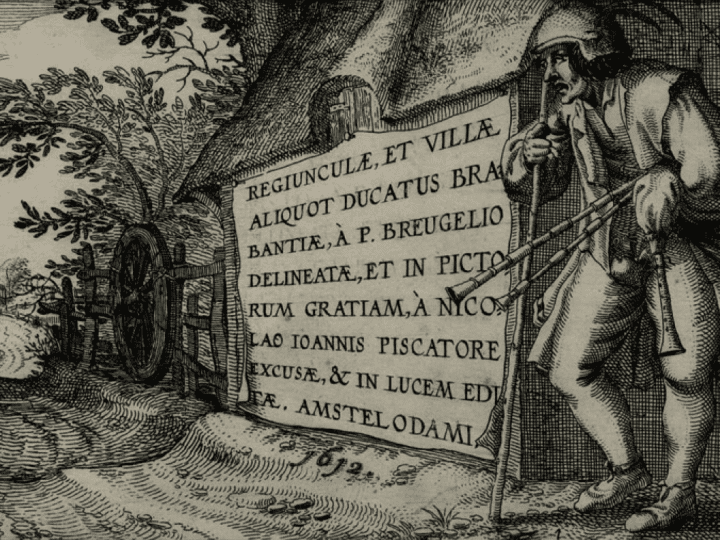

![Claes Janszn Visscher, Bleaching Fields by the Dunes (from the series Pleasant Places [...]), ca. 1611-14, etching, 10.3 x 15.8 cm](https://jhna.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Sluijter1.2_08c-112x84.jpg)