From the mid-sixteenth century, Antwerp saw an explosion of printed histories, etymological research into place names, and Netherlandish dialects, as well as the publication of Dutch dictionaries and grammars. Simultaneously, Antwerp’s art market saw a boom in the production of peasant scenes and the rising fame of Pieter Bruegel the Elder. In this article, I will argue that in both pictorial and textual representation, the peasant acted as a metaphoric vehicle, a type of living archaeological record and embodiment of local history, central to the production of a uniquely “Netherlandish” vernacular cultural identity.

For two days in 1520, extreme low tides exposed a ruined structure in the vicinity of Katwijk-op-Zee, a seaside village near Leiden. The Netherlandish historian Cornelius Aurelius was the first to describe what he termed “the tower of Calla,” a stone ruin visible at low tide from the shore; he postulated that the tower was the remnant of a Roman frontier fort.1 He hypothesized that the fort, positioned at the mouth of the Rhine, had been used by the Roman army as a base for excursions to Britain. The site thus became known as the Arx Britannica, or Brittenberg. By the middle of the sixteenth century, the ruins at Brittenberg were famous enough to merit inclusion in Sebastian Münster’s 1550 Cosmographiae universalis (fig. 1).2 Subsequent low tides in 1552 and 1562 led to further excavation of the site.

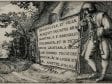

The Arx Britannica was also the subject of one of Abraham Ortelius’s earliest published maps, executed between 1566 and 1568 (fig. 2) and published in Antwerp.3 Although the sheet is undated, surviving letters indicate that Ortelius had discussed the Arx Britannica with both the esteemed numismatist and antiquarian Hubertus Goltzius and the philologist Guido Laurinus from 1566; both may have been active collaborators in the map’s production.4 Ortelius produced the first known plan of the archaeological site, inserted into a topographical view of the landscape. The cartographer also included snippets of text on the Batavians from Tacitus’s Germania, images of several items found at Brittenberg: stones bearing inscriptions and carvings, as well as an intact roof tile from the original antique structure. First issued as a separate sheet, the map would also be incorporated in the 1581 edition of Ludovico Guicciardini’s Descrittione di tutti i Paesi Bassi (Description of All the Low Countries). Guicciardini had included a textual description of the ruin in his original 1567 text, describing how local peasants had found stones inscribed “x. G.I.” (which he took to mean ex germanae inferioris [of lower Germany]), as well as several medals and other antiquities near the site.5

The antique ruins of Brittenberg, far to the north of Antwerp, were described and promoted by later-sixteenth-century humanists based in the city on the Schelde as being particularly representative of the Low Countries’ unique historical cultural identity. Ortelius’s image of the site is a strange jumble of texts, schematic plan, topographical view, and, crucially, also something approaching a genre scene. The laborers at work excavating, or perhaps removing stones from the site, are most likely peasants. These laborers are clearly from a lower order than those figures represented as approaching on foot and in coaches to look at the site – one laborer even doffs his hat as a pair of figures approach the ruin.

During this period, sites of archaeological importance were often first discovered by rural people engaged in plowing fields and other agricultural tasks, who brought inscribed stones, medals, and other items to the attention of scholars and the wider public. While some blamed peasants for stealing or reusing antique stones and objects, others, like the numismatist Guillaume du Choul, relied on agricultural workers bringing him antique coins to study.6 In the case of Brittenberg, Guicciardini acknowledged the peasants’ role in finding antiquities at the site and in publicizing the ruin, yet he also insinuated that the peasantry was ignorant and pilfered stones from the site.7

Thus, the peasant unearthed the remnants of antiquity but remained unaware of the importance of his find. Ortelius shows the ruin itself in a schematic perspective, with the result that the peasants dig and move stones around a curiously two-dimensional pictogram hovering in a somewhat flattened perspectival space. While the peasants engage with the ruin at the level of the stones themselves, the viewer confronts the schematic plan of the ruin. It is the buyer of Ortelius’s print, the reader of Guicciardini’s text, who must make sense of the archaeological discovery, to build a history around the artifacts found and unrecognized by the peasant.

I have begun with this unusual map because I believe it represents the complex nexus of ideas at play in the late sixteenth-century Netherlandish concept of a “vernacular” culture as a place where classical antiquity, local history, and the peasant meet. It was in Antwerp, the multicultural, mercantile, intellectual, and publishing center of the Low Countries, where multifaceted and often conflicting concepts of the vernacular were produced. The incipient field of archeology, the growing interest in the collection of language and customs, and the representation of the peasant in both text and image, all had a role in this process.

Defining and Defending the Vernacular

In the most direct sense, the word “vernacular” (from the Latin vernaculus, meaning domestic or native) is taken in English to mean local language and idiom. The second half of the sixteenth century saw the widespread publication of multilingual dictionaries and grammars resulting in an increasingly systematized Dutch vernacular.8 The demand for dictionaries was itself the product of the runaway success of the printed media, in particular, the demand for translations of popular works and the need to disseminate information – be it governmental edicts, humanist ideas, religious views, geographical or scientific discoveries – across linguistic boundaries. Reflecting the perceived necessity for vernacular translation, Cornelis van Ghistele, in the preface to his Dutch translation of the Aeneid, lamented: “menich constich gheest daerduere hem ontsiet ende grouwelt yet in onser Dutyscher talen over te settene (many an artful mind is frightened and recoils from translating anything into our Dutch language).”9

To assist in the process of translation, Dutch dictionaries, like the Latin-Greek-French-Dutch Dictionarium tetraglotton published by Christopher Plantin in 1562, began to appear with regularity in the later sixteenth century. Yet the systematization of the vernacular was not only aimed at easing the task of the translator. The Antwerp lawyer Jan van der Werve, in his 1553 legal dictionary Het Tresoor der Duytsscher Talen, argued for the increased use of the vernacular by appealing to the historic character of the Dutch language, writing:

Helpt my ons moeders tal (die ghelijck goudt onder d’eerde

leyt verborghen) wederom so brenghen op de beene, dat sy

aen andere talen geen onderstant en behoeft te versoecken.(Help me, to raise up our mother language [which now lies

concealed in the earth like gold], so that we may prove how

needless it is for us to beg for the assistance of other languages).10

Van de Werve not only uses the evocative term, “mother tongue,” for the vernacular, he also compares the Dutch language to an archaeological find or precious natural resource, lying buried beneath the earth.

The use of the vernacular was thus increasingly mobilized as a unique cultural and historical asset.11 Van de Werve’s appeal was aimed not only at increasing the use of the Dutch language but also at codifying and preserving it. This meant eliminating foreign words from the language. In 1559, Van de Werve would go so far as to republish his dictionary, replacing the French-derived Tresoor in the title for the more suitably Dutch Schat. Dirck Volckertszoon Coornhert also advocated a return to the purity of “onse nederlandsche sprache (our Netherlandish speech)” in the preface to his 1561 translation of Cicero’s De Officiis.12

The search for linguistic purity was often mixed with an antiquarian concern for the preservation of the perceived “historical” state of the language. The historical value of the Dutch language assumed phenomenal stature in the 1560s, reaching a climax in 1569 with Johannes Gropius Becanus’s assertion that Diets, the local dialect of Antwerp, was in fact a direct linguistic descendant from the language of Adam.13 While Becanus’s views remained extreme, historical accounts of European languages appeared with greater regularity in the later sixteenth-century, acknowledging the vernacular’s capacity to be transformed through time.14 Recognizing the historical value of the Dutch language allowed for the recovery of the past not only through the manipulation of the physical remains of antiquity at archaeological sites such as Brittenberg but also through linguistic research. Etymology, the study of the origins of words and place names, arose as a kind of textual archaeology and was used by Becanus, Ortelius, and Petrus Divaeus to establish the antiquity of Netherlandish towns and cities.15

The collection of vernacular oral traditions, such as songs and proverbs, was not unrelated to the etymological and linguistic interests of antiquarians and humanists. In the preface to Tylman Susato’s collection of songbooks published between 1551 and 1561, the publisher writes that he wants to celebrate “onse…nederlandsche moeder talen (our Netherlandish mother language,” as well as “onse vaderlandsche musycke (our fatherland’s music).”16 In a similar fashion, proverb collections such as Symon Andriessoon’s 1550 Adagia ofte Spreecwoorden, published in Antwerp by Heynrick Alssens, encouraged the historical valuation of the vernacular by gathering traditional idioms and publishing them alongside antique proverbs rendered into Dutch.17 Words, phrases, idioms, and songs could all be collected and discussed as representative of a distinctly Dutch vernacular, a language with its own historical value and scholarly merit.

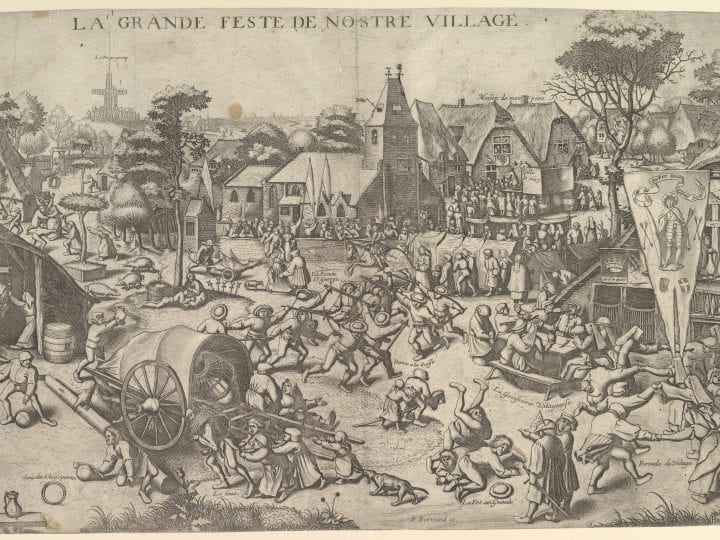

The peasant, besides playing a direct and active role in contemporary archaeological discoveries like that at Brittenberg, was also an important symbolic figure in the establishment of this Dutch vernacular. The music included in Susato’s songbooks often had rural origins, with the author indicating in the titles given to the songs, such as “de Poitou” or “for the Kermis of St. Jans.,” the particular village, region, or kermis where the song/dance was performed. , Perhaps the most famous example of this localization of songs and dances is Susato’s inclusion of a popular song associated with the kermis of Hoboken, represented by Pieter Bruegel the Elder in an engraving of 1559 (fig. 3).18 Both Susato and Bruegel transform the ephemeral products of a peasant culture into something to be consumed by an urban, educated audience, giving historical permanence to transient phenomena, as well as providing a validation of local popular culture. Custom, as a place where vernacular language, lived experience, and peasant practice meet, is an authoritative source for both artist and publisher.19

With few physical monuments or antique textual accounts to rival those of Rome, early Dutch historians had to find alternative foundations upon which to build their descriptions of the ancient Netherlandish people. Increasingly, a historical sense of Dutch identity was vested in linguistic and etymological research, as noted above, as well as in the collection of vernacular cultural traditions. Simultaneous with the explosion of printed dictionaries, songbooks, and proverb collections, Antwerp’s art market also saw a boom in the production of peasant scenes depicting rural villagers at work and, more often, at play. While the rise of the peasant genre in the visual culture of sixteenth-century Antwerp has been discussed in relation to the rise of an urban, bourgeois art market concerned with social distinction, moral temptations, and community ethos, the link between peasant imagery and the appreciation of Dutch historical vernacular culture has been less well studied.20

Not only was the figure of the peasant increasingly the subject of independent visual images (paintings and prints) in late-sixteenth-century Antwerp, but the customs of the peasant were also an important source for the writing of vernacular histories published in the city. Guicciardini and Ortelius would both refer to peasant costumes and customs as antique in origin and/or to ancient Netherlandish practices being like those of the contemporary peasant. Peasant culture, in much the same way as the Dutch language, could provide access to the past precisely where there was a local absence of texts or physical remains. The figure of the peasant was increasingly identified with a historical, even an antique, Dutch identity, in contradistinction to the increasingly urban character of the sixteenth-century Low Countries.

Bruegel’s Peasants and the Production of Local History

Pieter Bruegel the Elder is perhaps the most famous artist to depict peasant life in the period, and his peasant scenes have been mined for allegorical, moralizing, and comedic readings, while little consideration has been given to the links between Bruegel’s pictorial representation of peasants and the representation of peasant customs in contemporary historical, chorographical, and early ethnographic writings.21 In the remainder of this article, I will argue that the peasant, in both Bruegel’s images and in sixteenth-century histories and ethnographies, was represented as an embodiment of vernacular history, a kind of living archaeological record, as well as a metaphoric vehicle for the transmission of a distinctly Netherlandish culture.

Bruegel’s printed and painted peasants offer perhaps the most specific and tangible links to the broader interest in Dutch vernacular identity among Antwerp humanists. Hieronymus Cock’s publishing house, De Vier Winden (The Four Winds), which published most of Bruegel’s prints, had a parallel audience to that of Christopher Plantin’s press – an educated and international clientele interested in high-quality products.22 Cock’s prints were less expensive and more accessible than the more esoteric Latin texts of Plantin’s press. The documented patrons for Bruegel’s paintings mostly came from this broader audience, including civic administrators Jean Noirot and Niclaes Jonghelinck.23 Noirot and Jonghelinck probably had a working knowledge of Latin, but they were not necessarily as steeped in the classical tradition as a scholar like Ortelius.

It is important, however, to recognize the intellectual ambitions of Bruegel’s clientele, rather than dismissing their acquisitions as merely “mercantile.” In addition to sixteen paintings by Bruegel, Jonghelinck owned a series of panels depicting the Labors of Hercules by Frans Floris, as well as a series of bronzes by Floris’s brother Jacques, depicting Bacchus and the seven planets.24 Merchants, too, could be interested in antiquity and local history, without acquiring classical Latin or Greek. The widespread popularity of Guicciardini’s Descrittione di tutti i Paesi Bassi, which went through three editions in both French and Italian before 1590, also attests to the broader audience interested in a local vernacular customs and traditions.25

In addition to addressing a public that converged with that of the authors of local histories, dictionaries, and compilers of customs, Bruegel, perhaps most importantly, also shared these authors’ methodological concern with observation and accurate description, as well as cultivating his own particular awareness of local painterly tradition. Bruegel’s landscape prints have been connected to the contemporary philosophical interest in neo-Stoic principles, namely the Stoic ideal of detached observation of one’s surroundings, as well as to contemporary chorographic texts that mix geographic description and historical analysis.26 Yet the artist’s peasant scenes have not been discussed alongside similar historical texts that closely associate landscape with vernacular cultural traditions, particularly peasant customs.

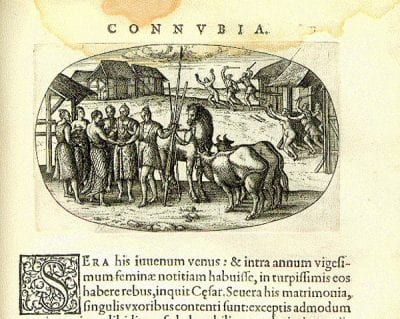

The methodological link between history, custom, and geography was itself antique in origin. Aristotle, Cicero, and Quintilian all used the commonplace of altera natura (second nature) to describe the intimate connection between a people and their physical environment.27 Custom was understood as a natural phenomenon, linked to a particular topography and cultural history. In his Histories, Herodotus had singled out particular types of customs and practices for discussion: religious rites, burial practice, marriage customs, and diet.28 Ortelius, in his 1596 Aurei Saeculi Imago, or The Mirror of the Golden Age, divided his short guide to antique Belgo-German civilization into similar sections, each with their own accompanying illustration.29 Significantly, this inherited model of cultural description often foregrounded peasant culture. While the genealogies of European nobility merited inclusion in the cosmography, the diet, costumes, and customs of the peasant were described more often than the courtly lifestyle of the nobility.

Guicciardini, for example, devotes the second division of his Descrittione to the “quality, and costumes of the men and women” of the Low Countries, after his discussion of the region’s geography and before a description of the region’s political system. The “men and women” Guicciardini describes are most often villagers and/or peasants. After briefly mentioning the fashionable dress of the nobility, Guicciardini specifically draws attention to the vagaries of regional countryside costume, citing this variation as continuing “from the time of Julius Cesar.”30 In the same section of text, Guicciardini devotes considerable space to reporting the typical Netherlander’s love of drink and feasting. Again, his examples are drawn from the lower orders, not from nobility – with the Italian famously claiming that the average Netherlander would travel twenty-five to thirty leagues to attend a kermis or wedding.31

In the early histories of the Low Countries, peasant custom took on particular importance as the antique Netherlanders, the Batavians, were consistently portrayed as “peasant-like.”32 Described in Tacitus’s Germania in a small section concerning the tribes of the Northern Rhine region, the Batavians are characterized as an agrarian people, though they are accomplished warriors.33 Tacitus describes the Batavians as living a pastoral existence, in contradistinction to urban Rome. The classical historian was avidly read in the sixteenth century and his style much copied. Germania was the antique source for the Batavian myth and Tacitus also provided the model for the writing of a non-Roman history.34

Aurelius, author of one of the first histories of the Low Countries, the famous Divieskroniek of 1517, based his depiction of the Arcadian, agricultural nature of Batavian society on Tacitus’s account, writing, “many notable points have been written by Julius Caesar and Cornelis Tacitus that I would like to record in my chronicle”35 Hadrianus Junius’s Batavia, which was probably finished in 1568 and was later published in Antwerp, was also directly modeled on Germania.36 In all of these texts, the Batavians are described as relative primitives compared to the civilized inhabitants of Rome. Yet this supposed primitivism is turned into a cultural asset, as a rural lifestyle is equated with honesty and simplicity. In perhaps the most famous example of this inversion, Erasmus’s 1508 adage “On the Batavian Ear” turned Martial’s epigram describing the ignorance of northern peoples into a celebration of the character of both the historical and contemporary Netherlanders.37

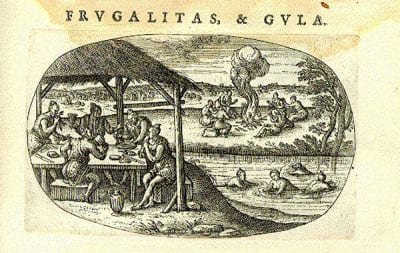

The specific visual and textual connection between the contemporary peasant and the historical Netherlander appears to have been a device particularly embraced by Antwerp humanists. As noted above, Guicciardini claimed that Netherlandish peasant costume had remained unchanged since antiquity. In his illustration (fig. 4) for Ortelius’s 1596 Aurei Saeculi, Pieter van der Borcht depicted an ancient German settlement as being similar to a sixteenth-century local rural community, with thatched roofs and predominately wooden architecture.38 Ortelius cites Caesar in noting that the diet of the ancient Belgo-Germans was based on meat, dairy, and bread.39 Aurelius described the Batavian diet as rich in meat and dairy, taking advantage of “rich pastures full of animals and…fruitful agricultural land.”40 This description of the Batavian diet and the bounty of the local landscape mirrors Erasmus’s account of the Netherlandish love of feasting: “The reason for this [feasting] is, I think, the wonderful supply of everything, which can tempt one to enjoyment…partly due to the native fertility of the region, intersected as it is by navigable rivers full of fish, and abounding in rich pastures.”41 Over fifty years later, Guicciardini would also single out the peasant’s everyday consumption of bread, butter, and cheese, again attributing it to the abundance of the local landscape.42

Bruegel also paints a picture of a dairy- and beer-loving peasantry. In the Peasant Dance (fig. 5), for example, the artist includes a conspicuous mound of butter upon the table at left, alongside a half-eaten piece of bread and jugs of drink.43 Bruegel paid close attention to the vertical form of the butter, as well as to the small dish of salt next to it, and the various forms of ceramic drinking jugs used by the peasants. In their specificity these details parallel those offered by Guicciardini and Ortelius. Guicciardini, for example noted the contrast between the austere everyday diet of the Netherlandish peasant and the more sumptuous fare consumed on feast days.44 In Peasant Wedding (fig. 6), Bruegel indicates this richer peasant diet, complete with meat and rijstpap, which is shown being washed down by the copious amounts of beer poured by the peasant at far left.45

Bruegel’s wedding feast takes place inside a barn stacked high with straw, evoking the abundance of the local landscape. Van der Borcht’s illustration of the ancient Germans feasting in the Aurei Saeculi (fig. 7) is reminiscent of Bruegel’s image,46 as both picture celebrants drinking heavily and dining on bread as well as a kind of porridge. In van der Borcht’s engraving, the feasting Belgo-Germans are seated outside and the artist includes a landscape view. The juxtaposition of feasting peasants, the fertile landscape, and the bounteous foodstuffs of the Low Countries also occurs in Bruegel’s Peasant Wedding.

The conviviality of the Netherlandish people at weddings and other festive occasions was also often cited by authors describing the Low Countries of antiquity and of the sixteenth century. Erasmus admitted that the Netherlandish race was prone to excess but qualifies this vice, stipulating: “If you look to the manners of everyday life, there is no race more open to humanity and kindness.”47 Ortelius’s description of the ancient German peoples also stressed their hospitality (“hospitijs auc convictibus”), as well as their propensity for excessive drinking (“continuare potando nulli probrum”).48 Aurelius described the Batavians in a similar fashion.49 Guicciardini writes that the Netherlander’s “vice is drinking to excess…but this is somewhat excusable because the air of the country is most of the time humid and melancholic.”50 The festivity of the Netherlandish peasant is consistently described as both a contemporary and a historical phenomenon.

Bruegel’s particular interest in the diet and customs associated with weddings parallels that of contemporary cosmographers or collectors of customs. The artist’s peasant wedding scenes include a number of specific details related to local marriage customs. In the Peasant Dance these include: the crown hanging above the bride’s head, the commemorative ribbons adorning the bagpipers’ instruments, and the color of the rich saffron porridge, to name just a few prominent examples.51 These are the kinds of culturally-specific details found in contemporary ethnographic collections and histories. Aurelius and Ortelius, for example, both describe the specific exchange of gifts (arms and animals) in the Batavian marriage ceremony.52 Both Bruegel and the historian are interested in the particulars of these practices, making a claim either to firsthand observation or to direct sources who described such behavior.53

Bruegel’s peasant pictures not only reproduce specific, observed practices but also painstakingly describe the material life of everyday things. In the Peasant Wedding Bruegel carefully articulates the grooved indentations and variegated colors of the assortment of drinking jugs held in the basket at the bottom left. The artist includes details, such as the makeshift tray made from an unhinged door or the large upturned tub acting as a seat for the well-dressed man at far right, that seemingly attest to witnessed practice.54 The artistic deliberation and specificity of detail mirrors that of Ortelius, who describes the various types of dwelling inhabited by the ancient Belgo-German in Aurei Saeculi, and by Guicciardini’s numerous lists (including those of rivers, forests, walled towns, and villages) in the Descrittione. Both authors and the artist claim authority as compilers of information. Ortelius primarily cites authors from antiquity – Tacitus, Caesar, and Pliny. Guicciardini draws upon the same authors but also upon his own careful observations and firsthand research, which he revised and expanded in the numerous editions of the Descrittione. Bruegel’s images, in their attention to material detail, appear to replicate Guicciardini’s methodological claims.

The methodological connection between Bruegel’s images and contemporary histories and collections of customs extends beyond a shared interest in everyday experience. The artist and contemporary cultural historians emphasize particular moments within cultural life: childhood (Children’s Games), feasts (Peasant Wedding, Kermesse at Hoboken), religious customs (Battle between Carnival and Lent), costume (Peasant Dance, Ice Skating outside St. George’s Gate), and weddings (Peasant Wedding, Peasant Wedding Dance). Nearly all of Bruegel’s peasant pictures take one of these topoi as subject, and these are precisely those areas described by Ortelius, Guicciardini, and other early historians.

In all of these textual accounts peasant culture is constructed both as “ancient” and as different from that of the urban, literate populace who consumed these early cosmographies, histories, and collections of customs. Peasant custom is understood as an unchanging type of historical remnant, a contemporary and observable example of a primitive culture. Within his images of contemporary peasants Bruegel repeatedly includes details and practices that are often specifically discussed as historical survivals in contemporary texts (such as costume, vernacular architecture, feasting practices) and pays them particular attention. The audience for Bruegel’s peasant paintings likely had some exposure to texts like Guicciardini’s, as well as to other early histories and collections of customs that described peasant culture as historic, which would have shaped their understanding of the artist’s peasant scenes. The peasant, as pictured by Bruegel, could simultaneously operate as contemporaneous “other” and as historical figure.

Antwerp humanists did not invent the concept of the peasant as historical remnant – again, it is a trope dating back to antique thought, perhaps best summarized by the classical proverb “Nemo sic mores vetustos estimat ut rusticus (No one keeps old customs like a peasant).”55 The peasant represents a repository of old, and possibly forgotten, customs, in the face of a rapidly changing environment. As we have seen, sixteenth-century authors drew upon this proverbial knowledge of the peasant in diverse ways: collectors of customs and costumes turned to the peasant as subject, while cosmographers and chorographers often used peasant practice as a point of comparison, a way to describe ancient mores. Contemporary collections of customs may not have provided a direct model for Bruegel’s pictorial practice, but both the historian and the artist share a methodological interest in certain “markers” of culture – particularly the diet, costume, and festive customs of the peasantry.

Inventing History

Reinhart Koselleck, one of the great modern explicators of the emergence of a concept of history and historical change, here provides us with a useful observation on the relationship between time, history, and cultural difference, drawn from his analysis of the historical thought of the Hellenic world. Koselleck remarks that the difference between the barbarian (the non-Greek) and the Greek or Hellene is that the Hellene used to be like the barbarian. The barbarians’ contemporaneousness is perceived in terms of their noncontemporaneous cultural level.56 In other words, the “other” is presented as the pre-evolved state of the dominant culture. Koselleck’s formulation demonstrates how contemporary cultural differences are constructed within a historical perspective and given a temporal dimension. Guicciardini’s assertion that Netherlandish rural dress had remained unchanged since antiquity or van der Borcht’s imagining of ancient Belgo-German settlements as being like peasant villages reveals a basic assumption about peasant culture as fundamentally static, in contrast to the evolved culture of the urban populace.

So, whereas the town-dweller belongs to a civilization with its own history, peasants and primitives do not have a history; instead they represent the prehistorical state of “civilized” man. When early explorers encountered the native peoples of America, Asia, and Africa, their touchstone for comparison was always the European peasant.57 The peasant, like the “savage,” remained untouched by the technological and social “advances” of urban Europe and was a living embodiment of Renaissance Europe’s own cultural past. Rural society was perceived as temporally immobile, exhibiting a way of life unchanged since antiquity, because of the supposed impossibility of social progression within peasant life.58 In comparison with the rapid growth of urban, socially mobile middle-class populations in the Low Countries, the sixteenth-century peasant was seen by his contemporaries as existing within a vacuum of time.

This characterization of the peasant as a temporally immobile figure was part of a broader process of social distancing that occurred between the subject of these images and the middle to upper-class viewer. The peasant operated as both a negative and positive model of behavior59 and was utilized both as a living link to the Arcadian past and as a reminder of contemporary social distinctions. For example, when the 1561 Haagspel, the secondary contest within the larger rhetorical competition known as the Landjuweel, posed the question of which underrated occupation was the most useful and honest, the unanimous response was agriculture.60 Although the guise of the peasant could be used to represent virtuous Arcadian abundance, in many of these same processions and plays the contemporary peasant was satirized as a figure of crude excess and exuberance.61 Bruegel’s images may celebrate the historical continuity of Dutch vernacular customs, but they also delight in the rough features and lumpy bodies of the peasantry.

Despite the symbolic temporal and social immobility of the peasantry in contemporary discourse, socioeconomic circumstances meant this static image of the peasantry was increasingly a fiction. In Bruegel’s lifetime, many peasants came to the city for employment, and the countryside was drastically altered by the effects of cottage industries like linen production, as well as by the colonization of the rural landscape by wealthy owners of the country villas called spelhuizen.62 Outside of cities, new technologies allowed for vast land reclamation, construction and drainage projects that were completed largely through the use of peasant labor.63 Yet the peasantry’s nonagricultural labor is conspicuously absent from Bruegel’s images, which primarily focus on the traditional labors of the months, for the most part unchanged for centuries, and festive practices perceived to be ancient in origin.

Peasant culture was seen as historic but as having no history of its own. Therefore, it was possible to collapse the distance between, say the diet and costume of the ancient Batavians and that of the contemporary peasants of Brabant, as does Guicciardini, or between the vernacular architecture of the ancient Germans and that of the contemporary Netherlandish peasant, as does Ortelius. Because peasant life was seen as unchanging (having no historical evolution of its own), it could be used as a substitute for the past.

Reflecting this curious temporal condition, Bruegel’s peasant pictures engage with history in a different way than the customary painting of historia. Bruegel did paint a number of pictures that meet the Leon Battista Alberti’s conception of historia – for example, the Massacre of the Innocents, Christ Carrying the Cross, and The Suicide of Saul. But the paintings under discussion here are different: although they are of the large scale typically associated with history painting, they are non-narrative, nonhistorical genre scenes. The subjects of these pictures do not derive from any specific classical or biblical text, their authority comes rather from the depiction of practices rooted in cultural tradition and the shared experience of the community. In The Battle between Carnival and Lent, for example, Bruegel displays a variety of costumes and customs that range from street performance and the cooking of waffles over a fire to the masked and stuffed bellies of carnival revelers. This Rabelaisian abundance of details calls upon the viewer’s own experience and the picture’s own internal logic to such great effect that Bruegel’s pictures are understood as authoritative documentary material and still used to illustrate histories of carnival customs.64 Bruegel and the contemporary cosmographer or historian, as well as the collector of customs, all used this type of unauthored and communal authority as an unwritten source of historia.

Bruegel’s specific attention to peasant custom in panels of a size typically reserved for history painting parallels the burgeoning appreciation for the representation of historic peasant culture. Bruegel depicts peasant practice on a monumental scale, granting humble vernacular customs pictorial status equal to that of antiquity or biblical history. In a similar fashion, Ortelius and Guicciardini include descriptions of marriage customs and diet, laws and family life, the latter alongside royal lineages and traditional histories, in their representation of various populations. The living and breathing culture of the everyday is integrated into the fabrication of history.

In Ortelius’s map of Brittenburg, the example with which I began this essay, the peasant also mediates between the physical remains of the past and the historical knowledge of the present. The contemporary peasant and the antique past are brought into contact through the discovery and manipulation of archaeological remains, as well as through their own lived experience and vernacular traditions. In both pictorial and textual representations, the peasant acted as a metaphoric vehicle, a type of living archaeological record and an embodiment of local history.

Bruegel’s innovation as an artist was to take subject matter that had existed, perhaps in other media, such as prints and decorated domestic objects, as well as in cheaper types of painting such as linen painting, into the medium of oil painting, marketing it to the upper middle classes who were interested in local custom, both as a source of amusement and as a historic vehicle.65 Bruegel was also interested in the continuity of historical artistic practice, transposing painting techniques derived from the local tradition of linen painting into the medium of oil and the skills of a miniature painter to a larger scale.66 The result was his own distinct painterly idiom, capable of producing paintings composed both of broad strokes and minute detail. Bruegel thus not only displays historical cultural practices in panels like Peasant Wedding or Battle between Carnival and Lent, as collected and described by sixteenth-century ethnographers and historians, he also paints these customs in a self-conscious mixture of traditional painting styles. Just as peasant culture can be seen as historical, so can the way Bruegel depicts peasant practice, in paintings on the scale of history paintings and in a style faithful to longstanding local practice.

Crucially, Antwerp was the primary center for the production of both vernacular peasant imagery and the numerous maps, dictionaries, and histories of the Low Countries – many of which, like Ortelius’s map of Brittenberg, explicitly referred to peasants and/or peasant custom. The link between a historical agrarian population and the contemporary peasantry was also apparently unique to historical representations of the Low Countries, although the concept of the “primitive” was key to both German and English sixteenth-century histories.67 While the interest in collecting customs and costumes was part of a pan-European interest in the local, and the fascination with the antique history of Northern Europe was indebted to the broader resurgent popularity of Tacitus’s Germania, it was in Antwerp where the production of a uniquely “Netherlandish” vernacular history and cultural identity would take hold.

Instead of reconstructing a narrative history showing how Bruegel’s images of peasants and contemporary histories and collections of costumes influenced and quoted each other, I have proposed here a more nebulous relation, closer to the definition of a network, as recently proposed by Krista De Jonge, whereby influence travels in multiple directions and flows in successive currents.68 The idea of the peasant as a historic remnant had a particular cultural currency in the later sixteenth-century Low Countries that was centered around the intellectual output of the Antwerp humanists but was also felt in rival civic centers (for example Nijmegen) and extended beyond a narrow academic circle. Bruegel’s own move to Brussels in 1563 did not mean he was removed from an interest in vernacular history or, indeed, from similarly concerned clients and friends in Antwerp, such as Jonghelinck or Ortelius.

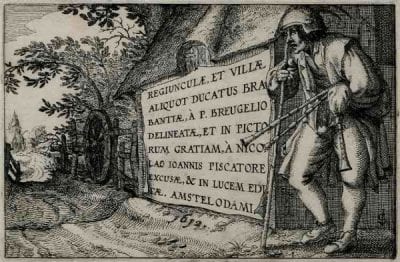

Peasant imagery represented a particular strain of Antwerp’s networked production of a vernacular culture – a product that proved so successful it would lead to the establishment of an industry devoted to the Bruegelian peasant image in the years following the Dutch Revolt. In the years after 1600, the Bruegelian peasant scene would itself become the subject of a nostalgic glance backwards and the production of a new Dutch vernacular. The Amsterdam publisher Claes Jansz. Visscher, in the 1612 title page for his condensed series of re-etched copies after the uncredited Small Landscapes (fig. 8) originally published in 1559 and 1561 by Hieronymous Cock, neatly pictures this relation.69

The series of Brabantine countryside landscapes, which Visscher claims were drawn from life, have been reattributed to Bruegel and a suitably Bruegelian bagpiper is positioned next to the series’ new descriptive title. Published in the Northern Netherlands after the devastating and protracted war with the Spanish, these image of the pre-war Flemish countryside would evoke nostalgic recollections of a lost past and place for the thousands of émigrés to the newly established Dutch republic in the north. Yet this image of the historic Flemish past and the Brabantine landscape is bound to the figure of the peasant, as pictured by Bruegel fifty years earlier. Despite the fact the Small Landscapes were not the inventions of Bruegel, it is Bruegel’s peasants, perhaps unsurprisingly, who have become synonymous with a historic Flemish local identity.